Was Socrates Wrong?

Arguing with the Ancients

Dear Classical Wisdom Reader,

One of the most common misapprehensions about the ancient world also happens to be one of my favorite aspects of it.

Many times in the past (and, indeed, to this very day), the classics have been depicted as “correct”, that the ancients were right, that they knew something we don’t, and that we ought simply to do as they say.

But this, I dare say, is wrong. We shouldn’t automatically agree with them; we should argue with them!

You see, we aren’t supposed to accept everything the ancient thinkers said. Their words are not part of an instruction manual, telling us exactly how to live. Nor are their texts gospels to be followed piously. They should not reside on a pedestal, unquestioningly adhered to.

No. The fact of the matter is that they aren’t always right.

Some of the time, they got things wrong...really wrong. And our job isn’t so much to believe in them; it’s to engage with them.

This isn’t being disrespectful. Quite the opposite! It’s taking part in a long, beautiful, and storied tradition, engaging in the Great Conversation, one that goes right back to the ancients themselves. Indeed, the entire history of philosophy is composed of debates, conflicts, arguments, and counterarguments.

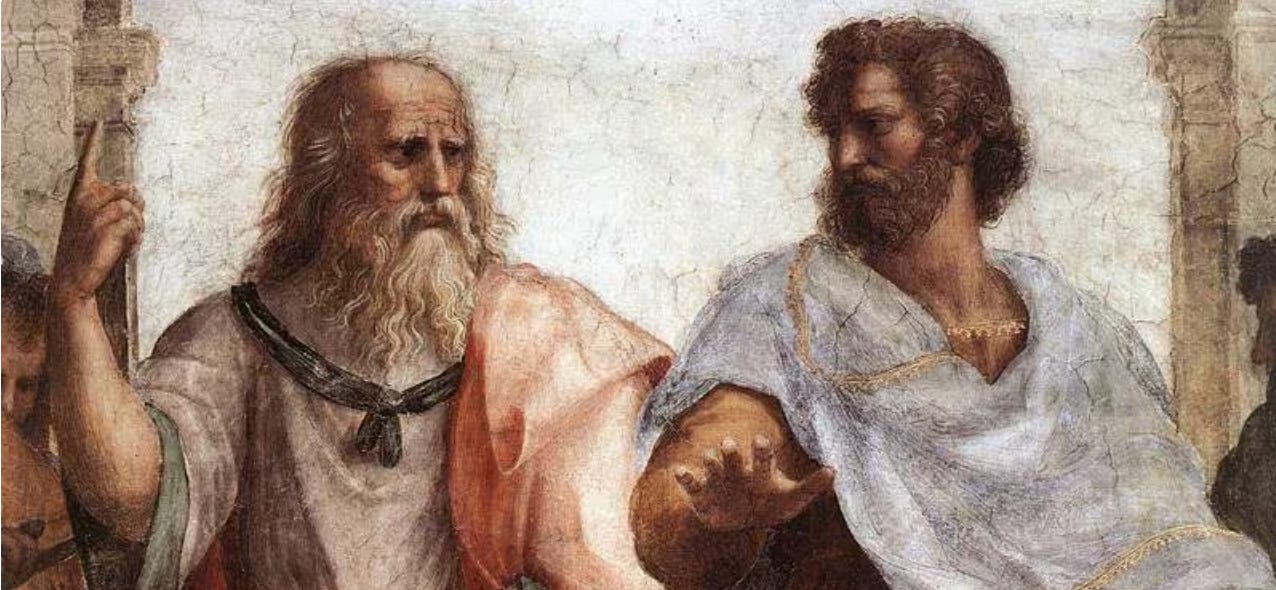

And this begins right at the very beginning, with the Greeks themselves. Where would we be if Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle had concurred on every point? Many of Aristotle’s central ideas were formed in opposition to his teacher’s, who in turn reacted against his own predecessor.

The Stoics and Epicureans were famously at odds, and through respectful (and sometimes sharp) discourse refined their positions on virtue, pleasure, duty, and fate.

And just think of the Cynics, their radical views on life, purpose, and convention set firmly against, well… everyone else.

This tradition of disagreement continued with the Romans, who not only debated among themselves but also wrestled directly with the texts that came before them.

Seneca, for example, challenged what he saw as overly theoretical or detached strands of Greek Stoicism, emphasizing instead moral urgency and practical engagement. Lucretius adapted Epicurean philosophy into a distinctly Roman poetic and materialist vision. Cicero, epitomizing the Academic Skeptic, questioned, compared, and synthesized nearly every school of thought available to him.

This Great Conversation continued into the medieval era and the Renaissance. Augustine of Hippo rejected the classical belief that human reason alone was sufficient for achieving virtue. Petrarch, often credited with igniting the humanist revival, famously wrote letters directly to ancient authors, pointing out where he believed they had gone wrong.

Logic, metaphysics, and cosmology truly accelerated once thinkers such as Petrus Ramus, Bernardino Telesio, and Galileo Galilei challenged Aristotelian frameworks that had long gone unquestioned.

Through conflict and tension, creativity, insight, and even harmony can be born, something my favorite Ephesian, Heraclitus, poetically captured as early as the 6th century BC.

And so, with this wonderfully liberating aspect of the ancient world in mind, we approach Plato. There are certainly elements of his work that are brilliant and profoundly illuminating… but there are other moments when, honestly, I’m not quite so sure.

Today, we will examine one such case...an argument that has divided readers for millennia, including many of Plato’s own contemporaries. Socrates has been condemned to death by hemlock and refuses to escape. His reasoning is that to do so would be unjust.

But were his arguments sound?

Was Socrates (and by extension, Plato) correct?

Read Alex Spieldenner’s take on Socrates and the Crito to explore Socrates’ claim, and ask yourself: do his justifications convince you?

Comment below, let me know what you think, and take your own place in the Great Conversation.

All the best,

Anya Leonard

Founder and Director

Classical Wisdom

P.S. Last week we explored more of Plato, his ideas, his legacy, what he got right and what he got wrong in our Podcast with Professors, featuring Angie Hobbs, Professor Emerita of the Public Understanding of Philosophy at the University of Sheffield.

Angie is a superstar in the philosophy world (indeed, she has the distinct honor of having the most BBC In Our Time guest appearances!) and her real expertise is in Plato... so unsurprisingly her insights are truly fascinating.

Members, if you didn’t get chance to watch or listen, you can still do so here:

If you aren’t a member, but would like to enjoy our full podcast, along with our other resources, such as our Classical Wisdom Litterae Magazine, Ebook library and Member’s only in-depth articles, make sure to subscribe today and let the ancients guide you:

Socrates and the Crito: Our Relationship to Law

By Alex Spieldenner, Aquinas and Beyond

What obligation do we have to our country? Do we have to follow laws when they harm us?

These questions get personal for Socrates in the Crito, where he is awaiting his execution after an unsuccessful legal defense of his philosophical method. Crito, a friend of Socrates, bribes the guard and tells Socrates that everything is settled for a daring escape. He just has to leave.

But Socrates refuses, leaving Crito aghast, even angry. He tells Socrates that he is being cowardly and unjust towards his friends by simply accepting death before it is necessary. And Socrates, true to form, offers to engage in a philosophical debate with Crito. If Crito can convince him that it is more just to escape, Socrates promises to leave. Thus begins a philosophical argument that, unlike most of them, is literally a matter of life and death.

Socrates first sets out to prove that escaping death is immoral by pointing out that if you have entered a just agreement, you must fulfill it or be guilty of injustice:

Socrates: Then I state the next point, or rather I ask you: when one has come to an agreement that is just with someone, should one fulfill it or cheat on it?

Crito: One should fulfill it.

The next step in Socrates’ argument is to show that he has entered into a just agreement with the city: namely, the agreement to follow the city’s laws in order to benefit from the city’s offerings.

Socrates: “Reflect now, Socrates,” the laws might say, “that if what we say is true, you are not treating us rightly by planning to do what you are planning. We have given you birth, nurtured you, educated you; we have given you and all other citizens a share of all the good things we could. Even so, by giving every Athenian the opportunity, once arrived at voting age and having observed the affairs of the city and us the laws, we proclaim that if we do not please him, he can take his possessions and go wherever he pleases…We say, however, that whoever of you remains, when he sees how we conduct our trials and manage the city in other ways, has in fact come to an agreement with us to obey our instructions.”

Socrates’ point is that his relationship with the city of Athens is not merely governed by what is always beneficial to Socrates. Rather, like any inter-personal relationship, it is governed by justice, and Socrates has obligations to the city because of the way that the city has benefited him throughout his life.

Notice that this argument does not rest on the assumption that morality is purely based on contractual language or social agreement. Rather, it is based on the belief that morally relevant relationships can be instituted, even implicitly, by agreement, including between a city and its citizens. When we benefit from the place that we live, Socrates thinks that we bear a responsibility to both the place and the people in it to work for its wellbeing.

Of course, it is possible for laws to be unjust, but Socrates is not the victim of an unjust law, because it is a law that he fully consented to participating in. Socrates points out that he had an opportunity to escape Athen’s legal system many times, but he chose to stay, implying that he was willing to abide by the decisions made by that system. Therefore, Socrates argues, he cannot leave once that system hurts him. Moreover, to reject a legal decision on the grounds that it hurts him would be to work towards the destruction of the entire system.

Socrates thinks that his own decisions have made him party to the workings of Athens and, now that they have turned against him, he must accept them as a child should accept punishment from a parent. Should a child with loving parents suddenly run away, or rob them, just because they have punished that child? Of course not; that would be unjust.

It follows then that it would be unjust to escape, no matter the physical harm he may receive. This is because of Socrates’ firm belief that moral or spiritual harm is a greater evil than physical harm, that the soul is of greater worth than the body, and therefore one should accept even physical harm rather than commit a harm against his or her own soul. Since committing an injustice would be a spiritual harm against one’s own soul, one cannot choose to do so, even for the sake of saving his or her own life:

Socrates: Above all, is the truth as we used to say it was…that, nonetheless, wrongdoing or injustice is in every way harmful and shameful to the wrongdoer? Do we say so or not?

Crito: We do.

Socrates: So one must never do wrong.

Crito: Certainly Not.

What can we understand from this dialogue? According to Socrates, the idea appears that our decisions truly bind us. We have obligations to the community in which we live, and when we seek to live only for our own benefit, we can cause harm. We can endanger the community and those in it by damaging the larger societal structures that hold it in place. Socrates remains a believer to the end that, for all its faults, he really has much to be grateful for from Athens, and considers its destruction to be equivalent to a kind of patricide.

Moreover, by living only for our own preference, Socrates contends, we are harming ourselves as well. When we commit an evil against another, the greatest harm is to our own souls: we corrupt ourselves into the kind of person who cares little for laws, less for other people, and less still for justice. That evil is even worse than death itself, and Socrates takes it to be obvious that, if he cannot escape morally, he would rather die. And so, by drinking that famed hemlock in 399 BC, he does.

Thank you for hosting my guest post!

Socrates whole stand was defending the Athenian laws and codes of justice during that time, which he rightfully did. On that point he was correct. There's no point in having laws and punishments if every convicted individual flees to escape what may be a just punishment. However, Socrates was convicted of "corrupting the youth of Athens" which gets lost in these discussions. Corrupting the youth sounds like a very subjective crime. I'm not sure if he had the ability to appeal or if that's a more modern convention, but when reading about the trial it doesn't sound like he defended himself very well and there were a lot of high ranking officials who were annoyed with what Socrates was doing. And on that point, defending himself, holding the Athenian justice system to its own high standards, and putting the accusers on the stand he was wrong.

Just my thoughts and happy to read what other people think too.