Was Socrates REALLY guilty of his charges?

Worshipping false gods and corrupting the youth...

Dear Classical Wisdom Reader,

It would be impossible to overstate the importance of Socrates… the man, his ideas, and his death.

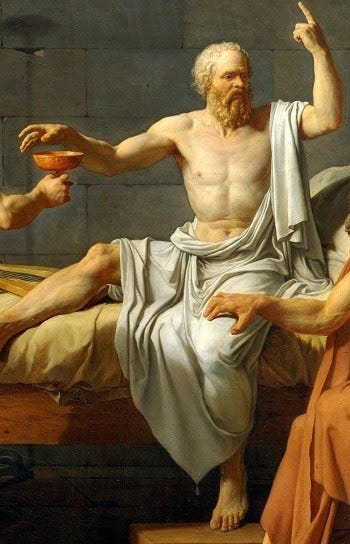

Indeed, it is his final act that has seared his importance into history… the grand accusations, the mock trial… and of course, that famous last drink.

This is because his death (and the records of it) are both a fundamental moment in ancient history and a catalyst for some of the most essential questions one can ever ask oneself.

Is there a soul? An afterlife? Are Laws always Just? What is morality? What is God?

Many of these important philosophical inquiries stem from the fact that the trial was such a sham…but what if Socrates was actually guilty? Could that be possible?

Before you delve into Ben Potter’s article below, a quick reminder of our exciting event, “How to Think Like Socrates” taking place TOMORROW.

Join us at NOON EDT to discover the Socratic Method, Leadership, Self-doubt, Civility and thinking itself with an all-star lineup.

Register HERE: https://socratic-method.eventbrite.ca

PLUS: If you register today, you can win a hardback copy of Massimo's soon to be released book, "The Quest for Character." Check out how here:

https://socratic-method.eventbrite.ca

Now, read on to take a deeper look at the charges against Socrates and whether there was any foundation to them at all….

In Case You Missed It… Articles from this week:

& from the Archives: The Eagle, or Aquila, Constellation

Was Socrates REALLY guilty of his charges?

By Ben Potter

399 BC saw the trial, imprisonment and execution of one of the most innovative and unusual thinkers the world has ever known.

Though we Classics enthusiasts are often guilty of bandying about terms like ‘great’ or ‘seminal’ with reckless abandon, there is no controversy in using such adjectives for Socrates.

This ugly, hulking, but surprisingly graceful chin-stroker had his long life truncated by the very citizens who he had served... with the sword, in political office and with his indefatigable pursuit of truth and wisdom.

That the premature striking down of such a colossus was both a travesty and a tragedy is common knowledge to us all, but one question we rarely investigate, indeed one that seems almost superfluous to the wit and wisdom contained the pages of The Euthyphro, The Apology, The Crito, and The Phaedo is: ‘was Socrates guilty of his crimes’?

The knee jerk reaction is ‘of course not’.

And indeed, the case Socrates makes in The Apology is both entertaining and persuasive, so persuasive that 220 jurors voted in his favor.

(For the sake of ease, we shall ignore the ‘Socratic problem’ from here on in...)

Therefore, did the 280 or so jurors who voted against him believe the charges were trumped up, but condemned him anyway out of malice or fear? Or, in fact, did they vote that way because the charges carried credible weight?

Well, before we sift through the nitty-gritty of the case, a bit of historical context is necessary.

Socrates was seventy years old at the time of his trial, thus we can assume he’d been a well-known, not to mention outspoken, Athenian public figure for the best part of fifty years.

Any member of such a relatively small society would inevitably accrue baggage after such a length of time, but a prominent and polarizing celebrity like Socrates couldn’t realistically hope to come across a dispassionate and disinterested jury.

This would have been augmented by the fact that Socrates lived through the most volatile period in the entire history of the Athenian city-state.

The question you’ve probably already inferred from this bout of historical throat-clearing is: ‘were some people out to ‘get’ Socrates’?

The answer is a simple ‘yes’.

Despite serving with distinction at the battles of Potidaea, Amphipolis, and Delium and even saving the life of the brilliant, controversial general Alcibiades, Socrates was a man with his fair share of political enemies.

One reason for this was because of the man he saved.

Alcibiades, the greatest general, turncoat and pervert of 4th century BC Greece, a man referred to by Xenophon as “exceeding all licentiousness and insolence”, was at the very least a friend, and, many believe, a lover of Socrates.

This, combined with Socrates’ (perceived) penchant for criticizing the Athenian democratic experiment, marked him down as one many treated with suspicion.

However, even when Socrates did his democratic duty, he still managed to make enemies. In 406 BC he was randomly selected to be the leader of the Boule, a council of citizens appointed to run daily affairs of the city. In this role, Socrates refused to sanction an (illegal) demand that the generals responsible for the catastrophic defeat at the battle of Arginusae be brought to trial en bloc.

Refusing to participate in the ire of the mob to flout the constitution did little for the aging philosopher’s popularity.

A similar, yet paradoxical, situation happened two years later.

Following defeat to Sparta in the Peloponnesian Wars, democracy was briefly suspended and an oligarchy of ‘thirty tyrants’ ruled Athens.

Despite the fact that Socrates was seen as a tacit supporter of this ill-fated group, he gained yet more enemies by defying their request to fetch an innocent man, Leon of Salamis, to be executed.

Indeed, had not democracy been hastily reinstated then, Socrates would, in all likelihood, have been executed even sooner than he actually was.

The fact that Socrates was a marked man with enemies galore is almost inarguable.

What is harder to swallow is the idea that the events of The Apology were a political ‘show-trial’ aimed at removing a subversive and unwelcome influence from the Athenian social sphere. After all, the thirty tyrants themselves had been granted amnesty, so what was it about Socrates that ground quite so many gears?

Here we get to the crux of the matter.

It is his reputation, not his innocence, which Socrates considers to be under attack at his trial. Indeed, this is how he opens his apologia, his defense.

Socrates claims that the charges brought against him by Anytus, Meletus and Lycon (an artisan/politician, a poet and an orator respectively) had nothing to do with the actual rap-sheet, but were driven by past irritations and embarrassments.

The professions of the above men are not insignificant.

They are effectively bringing about a class action against Socrates in response to the old man’s reaction to the Delphic Oracle, which claimed he was the wisest man in Athens.

To examine the veracity of this claim, Socrates went around town ‘testing’ the wisdom of prominent artisans, politicians, orators and poets.

They were all found wanting.

Interestingly, Socrates doesn’t dwell on his political reputation, but says this embarrassing inspection of the city’s brightest and best has woven a shroud of shame over his innocent activities. This wasn’t helped by the misconceptions that he is either a naturalist or a sophist.

As evidence of these unfair miscomprehensions, he cites Aristophanes’ The Clouds which features a particularly merciless character assassination.

It is telling that we can come this far along talking about Socrates’ crime and punishment without outlining what the formal charges actually were. This is a reflection of how Socrates’ felt towards the allegations brought against him; perhaps they were worth addressing, but only as a footnote to a general validation of his character.

So what were the three misdemeanors levied against the pursuer of wisdom?

That he corrupted the youth of Athens

That he introduced new gods/worshipped false ones

That he failed to worship the god of Athens

The first charge is a general one and seemingly impossible to refute, mainly because it is hard to understand what it actually means.

This is especially true from our point of view.

We look back on ancient Greece as an age in which child molestation and statutory rape were not only condoned, but considered a rite of passage and essential for a young man’s education.

What, therefore, could a man possibly do to corrupt a minor beyond sexually abusing him during a math lesson?

Well, in this case, it seems that Socrates merely made the young men of Athens defiant of the powers that be. Many youths in the agora would watch and learn as Socrates dissected the arguments of their elders and betters and left figures of authority looking rather red-faced and foolish.

That had to stop!

‘Corrupting’ the youth was a nice, generic term that, as it didn’t really mean anything concrete, could not be easily refuted.

Socrates, however, is no ordinary interlocutor. He makes his accusers not only concede that he is innocent of the charge, but that it is impossible for anyone to be guilty of it!

His broad argument runs thus:

corrupting the youth will make them worse

a man is negatively affected by those with bad characters

therefore, making the youth worse will actually make Socrates himself worse

a man will never, willingly, make himself worse

therefore, if Socrates has made the youth worse he must have done so by accident and deserves re-education rather than censure

So, despite the fact that charge 1 is almost meaningless, Socrates does enough to swat it away without difficulty.

It is under charges 2 and 3 that Socrates’ innocence hangs by a much thinner thread.

These accusations are often conflated together to one of ‘impiety’ or ‘atheism’ but this rather glosses over the truth of the matter.

Charge 2, that of false gods, does perhaps hold the most weight. Socrates freely admits that he has a daimon, a divine voice, who instructs him against taking the wrong path.

While today we could chalk up such a boast to intuition or thoughtfulness, it was taken quite literally by the Athenian public.

Socrates casually dismisses the idea that there is something sacrilegious in this by claiming anything divine must stem from the gods themselves – he’s again attempting to claim that the charge brought against him is an impossible one.

The major gripe against the daimon isn’t that Socrates hears the voice of god, such a phenomenon was relatively commonplace, it’s that, rather than spouting a cryptic piece of prophecy afterward, he’s getting direct and personal access to the supernatural world for his own personal benefit.

Socrates fails to successfully refute charge 2, indeed, he doesn’t seem to care if he has refuted it or not!

Charge 3, however, that he failed to worship the Athenian gods is paradoxically true and not.

Though he clearly believes they existed and, according to Xenophon, made regular sacrifices to them, he did not believe in the way that many wanted him to.

Much like most modern Christians, Socrates believed the more fanciful, ancient and immoral myths surrounding religion were stories or allegories.

He also propounded the notion that holiness was something loved by, rather than intrinsic in, the gods. Though he makes a logical case for why this is, it was not doubt radical and shocking nonetheless.

We can certainly say that, although there were those in society who wanted rid of Socrates, there was certainly some validity to the religious charges against him.

Even still, the main problem may not have been the offenses themselves, but that Socrates, a man who could argue his way out of anything, didn’t think they were particularly worth refuting.

Indeed, when cross-examining Meletus, Socrates gets him to admit that at the core of his accusation is the belief that Socrates is an atheist, which, of course, would mean charge 2 cannot be valid.

Socrates dismisses the problem with a weary waft of his hand, “I have said enough in answer to the charge of Meletus: any elaborate defense is unnecessary.”

Perhaps the most radical, and least observed, religious controversy which Socrates makes is hidden within The Apology’s most famous quote:

“I am that gadfly which God has attached to the state, and all day long and in all places am always fastening upon you, arousing and persuading and reproaching you.”

The famous ‘gadfly’ soundbite is actually the less extraordinary part of this sentence. What is truly remarkable is that Socrates freely claims that he is a gift from God (specifically, Apollo) to the state of Athens.

Socrates explicitly tells the jurors that he is a one-off, an unique entity, and they will be damaging the state if they execute him. The implicit suggestion, however, is that they will be murdering Apollo’s gift, effectively committing mass blasphemy if they find him guilty.

But, of course, they did find him guilty.

Legally, they were perfectly entitled to do this, the polis, the citizen body of Athens, was sovereign. Therefore, if he was found guilty by the people, he must be guilty, regardless of what the charge was.

However, taking a less obtuse approach, we could easily forgive the 280 jurors who condemned the great gadfly to death; they did so in accordance to the laws and conventions of the state.

That said, the trial and execution of Socrates goes down as one of the darkest chapters in the history of a great and greatly flawed civilization that brought us so much truth, beauty, tolerance and intellectual succor.

Whether they had the laws, or the gods on their side is a matter for ongoing debate... But those who led Socrates to his death will never be able to recoup a damaging debt of shame that subsequent generations have placed, and continue to place, upon their shoulders.

As the man himself puts it at The Apology’s conclusion:

“I prophesy to you who are my murderers, that immediately after my departure, punishment far heavier than you have inflicted on me surely awaits you... if you think that by killing men you stop all censure of your evil lives, you are mistaken; that is not a way of escape which is either very possible or honorable”.

Ah the Greeks... they gift democracy to the world, then vote to have their greatest philosopher put to death. There's a lesson in there... something about deriving ethics and morality from the "will of the majority."

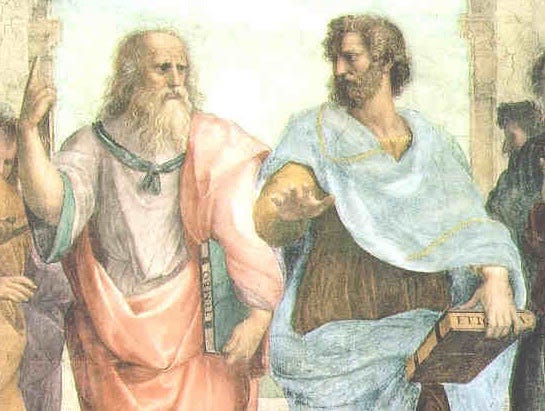

We know that Plato, throughout his life, was moving toward monotheism. Perhaps he got the idea from Socrates. History does not contain the answer.

The trial of Socrates was not unlike the trial of Christ. The charges against Jesus: that He claimed to be the Son of God, that He threatened the existing (Roman) order, that He was guilty of blasphemy punishable by death, parallel the charges against Socrates. Both men challenged the existing order and were deemed a threat by the powers that be. They had to go.

After the death of Socrates Plato became disillusioned with the institutions of men and in particular with government of and by men. In the Republic he argued that what the world of men needed was a Philosopher King, a man of great wisdom and understanding who could transcend the folly and the politics of both the polis and the powerful. He had seen and experienced in the most personal way what a world of men was capable of.