Why Do We Love Violence?

The Tainted Glory of the Gladiator

Dear Classical Wisdom Weekly Reader,

I’m not exactly a football fan. I’m more of a mild chicken wings and funny commercials kind of gal. But that doesn’t mean I haven’t enjoyed the spectacle of it all in the past. The rituals involved with the event, the cheering in the crowded bar, the knowledge of the shared experience, it can be intoxicating for sure.

That’s why the whole ‘concussion’ issue is so troubling. The evidence seems pretty conclusive that while we are all watching this extremely popular sport on TV and in the stands, the athletes on the field are seriously, permanently hurting themselves. Surely this has to stop!

But then again, haven’t we always sort of known this? I mean, huge guys are crashing into each other; what did we expect? And isn’t that sort of part and parcel of all violent sports since sport was created in the first place?

One only has to imagine the inherent violence involved with gladiators to know this is nothing new. Chariot racers had notoriously short careers due to notoriously short life spans. And right from the start, boxing and wrestling aren’t without their perils.

We haven’t even touched upon bull fighting, martial arts, pankration, rugby, cage fighting, etc...

The continuation of many of these sports goes to show that we modern audiences aren’t any less blood thirsty than our ancient spectating counterparts, whether we like to admit or not.

This brings us to the bigger question:

Why do we like watching violence? And, considering its universal and timeless appeal, is it ethical to enjoy it?

As always, you can respond to this email or write to me directly at Anya@classicalwisdom.com.

To add historical context to the question (which of course is our beat on these digital pages), please enjoy today’s article delving into the tainted glory of the gladiator. Who were the famed fighters? What position did they enjoy in society? And why was their superstardom so paradoxical?

Read on to understand more of the bloody sport that took the ancient world by storm.

Kind Regards,

Anya Leonard

Founder and Director

Classical Wisdom

From hate to love... this week we’ll be discussing love, according to the ancients. Surprisingly not all philosophers held the emotion up high. What did the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius advise? Classical Wisdom Members can find out on Wednesday with our Classical Wisdom Litterae Magazine, dedicated to love.

If you aren’t already a member, make this the day you join our growing community of Classics lovers, history buffs and philosophically inclined persons!

The Tainted Glory of the Gladiator

By Ben Potter

The sun rises high over Rome’s Amphitheatrum Flavium, the mightiest arena in the world. Only the colossal statue of Nero, which one-day will lend the stadium its eternal pseudonym, dwarfs it.

The 50,000 strong crowd of men and women, young and old, rich and poor, are tightly coiled; one giant organism ready to strike, to unleash their wrath or their joy.

Though they are not the only ones with the glint of attack in their eyes.

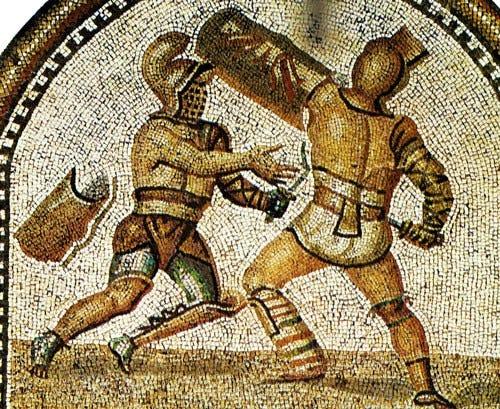

A flash of light leads to a clash of steel, a spray of sweat, a cloud of dust, and finally, brutally, a cascade of blood which unleashes a frenzied pandemonium in the stands…

Those cognisant of TV shows like Spartacus, films like Gladiator, or indeed, any example from the swords and sandals genre, will be familiar with images of perfectly formed behemoths attempting to heroically empty their comrades of their entrails.

Though, as we shall investigate, Hollywood has not quite given us the full picture. I know, I know… shocking isn’t it!?

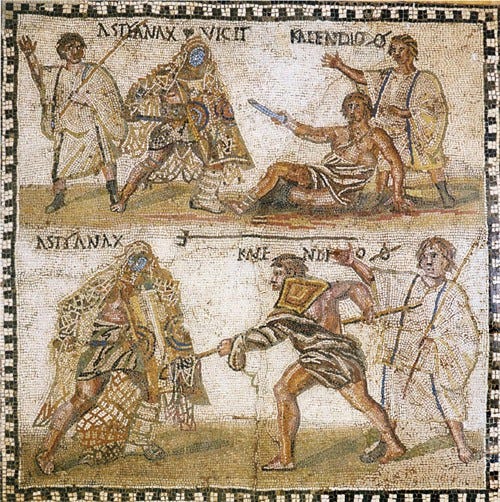

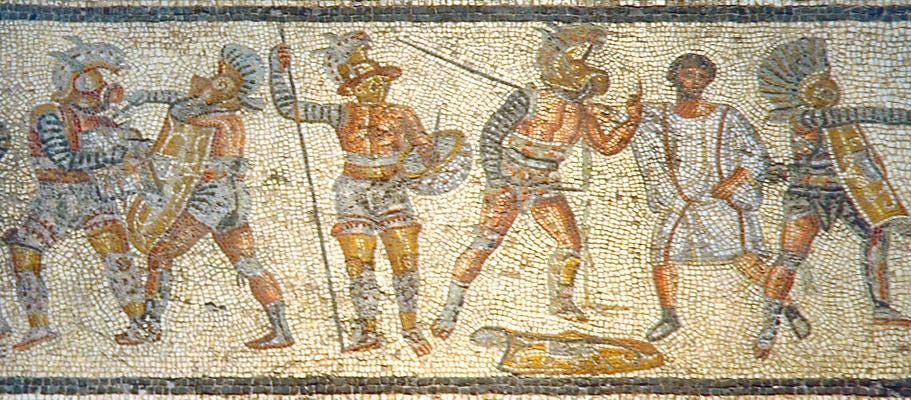

To begin with, gladiators were not perfectly formed. Indeed, they would be considered overweight next to modern sportsmen. Additionally, bloodlust was a secondary consideration to poise and finesse, and in fact, most gladiatorial bouts saw the loser escape with his life. Finally, and, crucially, large parts of Roman society considered gladiators to be anything but heroic.

As for the famous quote in the title (“Those who are about to die salute you”), it did genuinely occur in the pages of Suetonius.

However, it was supposedly uttered by a group of condemned men in an attempt to curry favour with the emperor, and not, as Tinseltown would have us believe, by every gladiator who entered the arena.

Indeed, it is highly unlikely that any professional fighter ever said it.

But before we conduct our gladiatorial post-mortem in earnest, perhaps a look at the origins of the sport is in order. (Unpleasant as it seems, it’s hard to deny that it was a sport – complete with match day programmes and scalpers selling tickets!)

As for the beginnings of gladiatorial combat, there is some dispute, though most agree it came out of the Italian peninsula… either from the Etruscans or Campanians.

What seems clear is that the games (ludi) were not intended to be the great public spectacle they later became. Instead, they were munera, a type of honorific spectacular dedicated to the spirit of a deceased ancestor.

What is really astonishing is how fast the event caught on. The first recorded munus was held in 264 BC, and within 200 years, their popularity and importance had become such that the Senate had to limit the size of the proposed munus of none other than Gaius Julius Caesar.

[N.B. Though if we compare how cinema has changed in only 150 years it is perhaps not so astounding.]

Even though the transition from munera to ludi was a gradual one, we can say with some confidence that by the time of Caesar, gladiatorial combat had mostly lost its connotations of filial duty. Instead, it had become a means of self-promotion and popular entertainment… and not just in Rome, but also throughout the rapidly swelling empire.

So what about the fundamentals of the games and, more importantly, the gladiators themselves?

A gladiator (from gladius, short sword) was the king of the sand, a mighty warrior, fiercely trained for one purpose only. He was a man of pride, dignity and above all else, discipline. He knew his life was forfeit and his only desire was to live and die with the stoicism and honour befitting his station.

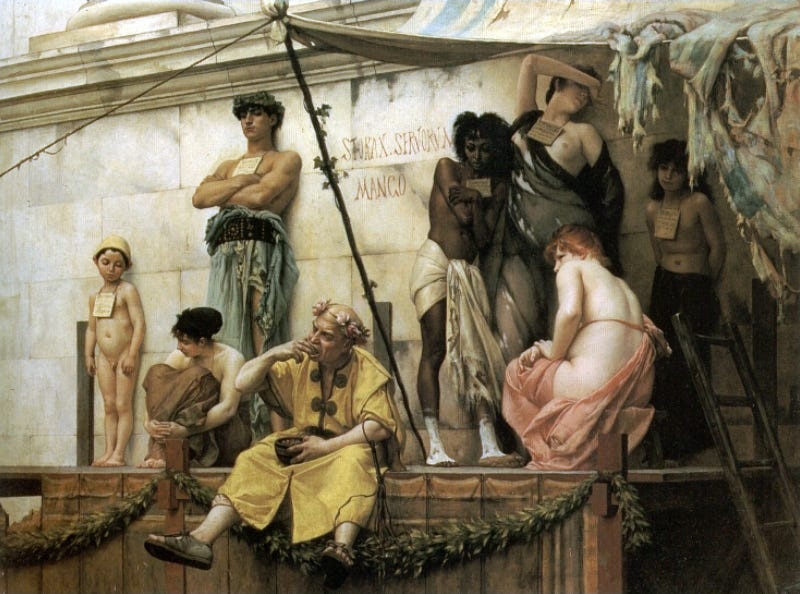

Despite the fact that gladiators were the celebrities and sex symbols of their day, they were also so deeply despised that the very word ‘gladiator’ was used as an everyday insult. They had no citizenship rights, were buried only with their own kind, and could have their lives expunged at the whim of their lanista (owner/overseer).

Essentially, they were a de facto category of slaves.

The antipathy felt towards these subhuman supermen is partly because of the social makeup of the gladiatorial class.

They were slaves of various origins: prisoners of war, citizens who had lost their rights or who couldn’t pay their debts, and various criminals from around the empire. Only if they were lucky, would they find their way into a ludus (gladiator school).

N.B. if they were unlucky they would merely be damnati (condemned to fight in the arena) or noxii (condemned to die a humiliating death in the arena). The difference being that the noxii would probably not be given weapons and their remains would be treated in a manner that would dishonour them for eternity.

All arenarii (people of the arena) were infames i.e. without rights or social status – a standing shared by prostitutes, pimps, actors and dancers. Gladiators, however, were both simultaneously far more lauded and reviled than any of these other controversial professions!

This was all very well for the impoverished, the enslaved and the criminal – indeed, many were happy to enter a ludus. It would mean good food (gladiators followed a high-calorie vegetarian diet), a roof over their head, and a potential to win money, freedom and that most intangible and strangely elusive of all things, fame!

Also, it got them out in the fresh air… which is nice.

The peculiarity, therefore, is not that many of the most desperate ended up in the arena, it’s that some of the more privileged actually volunteered for this ignoble and bloody fate.

Some scholars estimate that as many as half of all gladiators were volunteers (auctorati) by the time the games were at their height (1st century BC – 1st century AD).

But what really boggles the mind is that the lure of the games was so great that they even managed to entice aristocrats!

Indeed, it seems there was a significant minority of the noblesse who disgraced their family name, gave up promising political careers and disinherited themselves from great wealth. In fact, it was beholden upon Augustus, the moral champion of the 1st century AD, to make it illegal for the senatorial and equestrian classes to fight.

Despite the emperor’s absolute power, the prohibition seems to have had only limited success.

In addition, several emperors themselves are known to have stepped onto the sand. This created a bizarre paradox of a man at the top of the social ladder publically engaging in the most degraded and base activity possible within his own society.

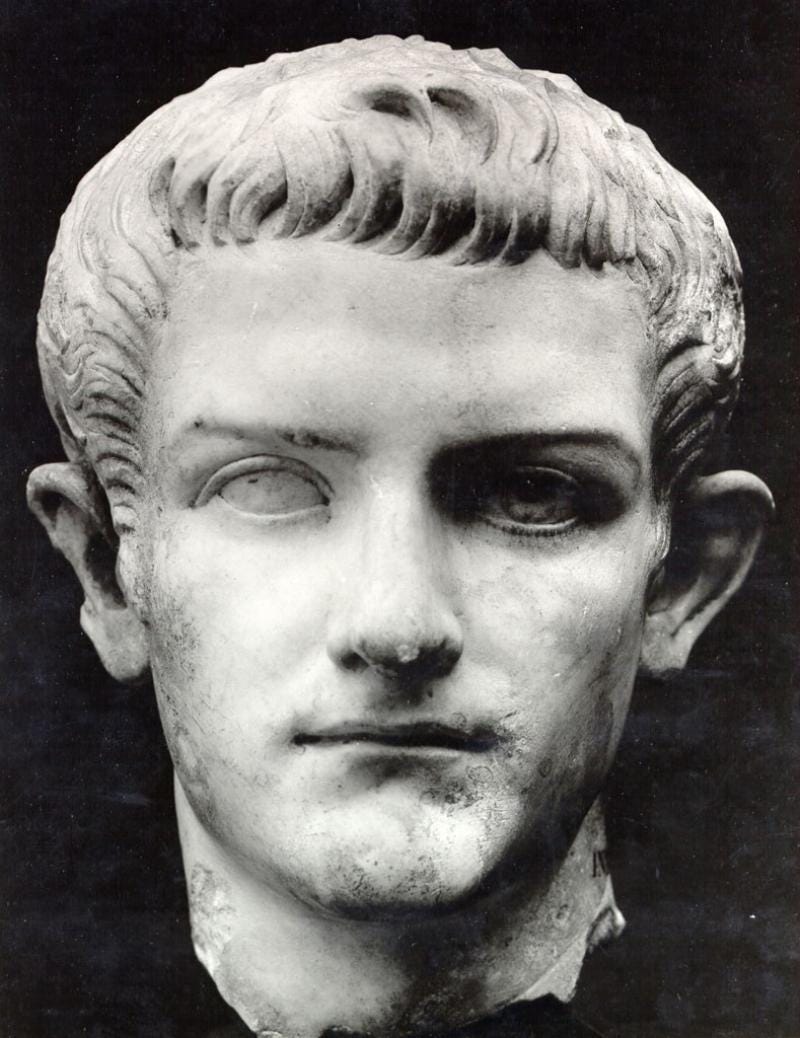

Caligula, Titus, Hadrian, Lucius Verus, Caracalla, Geta and Didius Julianus were all said to have crossed that stark line of dignity during their respective reigns. This was particularly amazing for Didius Julianus, as he was only emperor for nine weeks!

It is almost certain that none of the above competed with any seriousness and were merely making a populist parade of themselves or indulging a boyhood fantasy. (Though it’s hard to blame them; if I had unlimited power I would certainly insist on playing ten minutes of professional football).

However, the most enthusiastic, and therefore most shameful, participant in ludi was Commodus, the emperor who you may remember from that film with Joaquin Phoenix and Russell Crowe… the name of which escapes me.

Commodus was capricious, cruel and conceited (even by the standards of emperors). He was said to have killed 100 lions in a day and must, therefore, have had some physical and technical proficiency to avoid looking wholly ridiculous in front of the crowd; especially as he styled himself as the reincarnation of Hercules!

Indeed, the masses would have let him know if he had been entirely ludicrous. The games were one of the few conduits for egalitarian outpouring.

It was commonplace for the public to heckle, not just the participants of the ludi, but the on-watching ruling classes. In fact, it seems the games presented the ideal (perhaps unique) opportunity to present a petition to a politician in front of witnesses.

Though the games were unquestionably popular, (relatively) cheap to stage and helped school both combatants and spectators alike in the arts of war, they eventually fell foul in the later empire as a result of Christianity.

As early as the third century AD, the Christian scholar Tertullian denounced the games as murder, as pagan and as human sacrifice.

Perhaps it is no surprise that the first emperor to prohibit the spectacle was Constantine in the 320’s AD.

Though this was with little success; it was necessary to again curtail or prohibit the games in 384, 393, 399, 404, and 438 AD. By this latter date the Western Empire was dissolving into various warring factions and tastes in the Eastern Empire seemed more focused on theatre and chariot racing.

One of the hardest things for a classical historian to understand is the mentality of both the spectators and participants of a gladiatorial combat.

Though it obviously plays up to our baser instincts and, like so much sport, creates a tribal mentality, it goes so far beyond the most violent spectacles available to us today.

Regardless, there could have been nothing quite so dramatic, nothing that sent the heart aflutter and the limbs aquiver as the moment when a stricken gladiator raised a finger in submission, presented his neck to an opponent and all eyes turned to the editor (producer/sponsor) in whose hands the brilliant wretch’s life lay.

More than anything else, contemplating the bravery, daring and discipline of these ancient athletes only serves to highlight the egos, eccentricities and anti-social behaviour of their modern counterparts.

Despite doping, deflated pigskins, greasy palms and feigned injury, the worship, adulation and monetary rewards we bestow upon our physical elite shows no signs of abating.

Perhaps the Roman way is better, perhaps it’s a healthier approach: to marvel, to cheer, to applaud and goggle, but still, when the dust has settled and the blood has dried to remember that they are only mortal.

And much, much worse than that, that they are…yuck…entertainers!

Read up on Dopamine. It makes a dope of you. Pot, porn, gambling etc. all vices are Dopamine fixes. Self-control is job 1.

I've already replied once in notes, but now, having read the full article, I will write again. I am a woman martial arts master, and i qualified (many years ago) to train for the qualifier for TaeKwonDo in the Olymnpics. I really wanted to go out to California and train, but I did not have the money. But reality was not that far from my mind. I would not have qualified. Nice to be asked, though!

I studied martial arts (several, each at different times) first because my father violently abused me, and I wanted both revenge and safety. But once I outgrew my outrage, I wanted safety as a woman, and I also wanted a disciplined, courageous mind, since I am a coward at heart.

When I was young, I liked sparring because I wanted to test myself and improve and understand the necessary mentality of the calm, relaxed, self-possessed fighter. Combat is a mental game. But I did injure an opponent once, by accident, thinking he would stop as I came forwad. He did not, and with a single punch, I broke his nose and shattered part of his cheekbone and put him in the hospital. I quit for several years after that.

As I got older and advanced through the black belt ranks, I disliked sparring more and more. I did not want to hurt anybody. And the more experienced I became, the more I recognized that no matter how careful I was, I could still hurt somebody. As for me, I suffered a broken toe a couple times, was knocked out a few times, and had my ribs broken twice. I always came back.

But by the time I was third degree black belt (and I retired at fourth degree), I liked my fellow black belts, and I wished the new students well. I didn't want to spar any more, but I had to, so I did. And my reluctance did not stop me from decking a lower ranked black belt man who sassed me. Yes I could do that, and I did when I had to, but I didn't like doing it. In fact, my greatest anger was that some people pick a fight, and in the dojang, you have to put them down one way or another to keep your standing. I get mad at them for being such losers that they have to pick a fight. Usually, that type of person quits in the first year, but one or two go all the through to higher ranks.

I am glad I studied martial arts all my life. In October of 2022 I was diagnosed with Stage Three Cholangiocarcinoma, one of the super killers of cancers. My Christian faith is deeply colored with my martial arts mind, and I use the path to death to improve my mind and to exercise my faith. And God has been my friend through all the ups and downs and sufferings of cancer. So I'm glad I studied and practiced martial arts. As always, YMMV - Jeri Massi