Dear Classical Wisdom Reader,

We parked in an empty, dusty lot, inhabited by only a few stray and straggling dogs. The beating sun and parched air literally stole our breath when we opened the car doors. It was summertime in Greece and the heat up in the dry mountains was unforgiving...

You see, we were traversing Hellas for research, insights, inspiration and, of course, excellent photo opportunities. We started in Thessaloniki, right on Aristotelous Square, and after a few car rental mishaps and unlikely adventures, got on the road. We first stopped off in Vergina to check out the tomb of Philip II and see the sites of Ancient Macedonia. We thought we were finding a simple archaeological site... but instead, we found a fantastic mystery.

But before you delve into an excellent tale including a king or two, lots of gold, a warrior woman and battle scars, a quick reminder...

For those of you wishing to step in those same dark cool halls that have been holding such ancient secrets, as well as enjoy many more treasures in the Mediterranean and the opportunity to converse with your fellow Classical Wisdom readers... you are cordially invited to join the journey this September.

In fact, Verginia is just one of many fantastic stops on our spring 2024 voyage, which will explore the ancient sites of Turkey, Greece, the Greek Islands and Cyprus. From Knossos and Kusadasi to Priene, Philippi and Paphos, it will be a trip of a lifetime.

Learn more about our September 2024 trip HERE.

All the best,

Anya Leonard

Founder and Director

Classical Wisdom

PS: There is limited space on this voyage and cabins are already being snatched up. In fact, we were lucky to secure a few more cabins - but these remaining rooms will be opened up to the other group TODAY. So please make sure to take advantage of this opportunity and secure your spot, before they are all taken.

A Macedonian Mystery: The Tombs of Aigai

By Anya Leonard

It was a Thursday when we arrived outside the small town of Vergina to explore ancient Macedonia and Alexander the Great’s dramatic roots. The original name of the place was Aigai, the first city of Macedon and the resting place and palace of Philip II, father of the most famous Macedonian of all.

When we wandered over in the midday sun to the grassy mound that houses such intricate and telling treasures, we found the whole tomb to ourselves. Entering the refreshingly cool and dark chambers, the softly lit tombstones called out to us across the threshold, but only our footsteps echoed back in the damp solace for the dead. The excavated entrances to the tombs, complete with coloured architraves, were nestled deep in the earth, but the real treasures were displayed above. We peered at the elaborate golden wreath worn during the cremation, the beautifully constructed armor and weapons, as well as the golden chest, or larnax, which bears an embossed starburst, the emblem of the Macedonian royal family, and keeps the bones of the deceased king.

When Philip II inherited the throne in 359 BC, Macedonia was not the rich and powerful empire that it came to be. Surrounded by constantly invading and interfering enemies, the land was on the brink of collapse from both internal and external forces. Philip II’s ascension itself came after the death of his brother in the disastrous battle against the Illyrians, a campaign that resulted in the deaths of 4,000 Macedonian soldiers and the occupation of north-western Macedonia. It certainly wasn’t a monarchy that could afford the kind of wealth found in the tombs buried in Aigai.

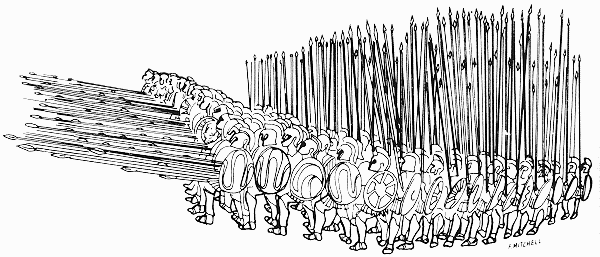

But then again, Philip II was a remarkable king. He took the potentially traumatic experience of being held hostage as child and turned it into a learning opportunity of superior Greek military tactics. Once on the throne, he fought off the Illyrians in his lands and then attacked Illyria itself. He issued his forces with sarissas, or long deadly spears, and promoted part-time soldiers into full time military men. With his now fortified army, the Macedonian King’s foreign policies became exponentially aggressive. Additionally, Philip II secured possession over the gold mines of nearby Mount Pangaeus, enabling him to finance his wars.

Throughout his reign, Philip II conquered Amphipolis and defeated the Thracians. He took the Greek cities Potidaea, Pydna, and Methone, as well as Thessaly. He subdued the Scythians and quelled rebellions. He married seven women who didn’t all try to kill each other. And he set the stage for a strong and impressive empire, one that his son, Alexander the Great, would fulfill.

But his military aggressions, ambitions, and excessive wives came at a cost. He was finally assassinated at his daughter’s wedding. It was the second day of the celebration and when Philip II entered the theater he was struck with a dagger and died instantly. The assassin Pausanias, a young Macedonian noble, attempted to escape but tripped and was killed on the spot.

The funeral for Philip II was greater than all previous kings. Alexander the Great lavished the tomb with gifts and treasures beyond anything that had been done before as tribute to his great, powerful and conquering father. These, we were told by the helpful descriptions at the museum, are the armor, the gold wreaths, the exquisitely crafted pottery found in Aigai…

… or are they?

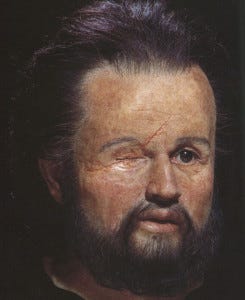

There is, in fact, quite a lot of speculation that the remains lying in the golden chest aren’t Philip II at all. Previous archeologists had labeled the well preserved bones as Philip II based on damage to the skull, caused, they believed, by an arrow which had penetrated Philip’s right eye either during the siege of Methone or while the king was inspecting the Macedonian siege mechanisms in 354 B.C.

However, there are a few inconsistencies, which makes the thoughtful reader doubt if this is evidence enough. Researchers have discovered that the style of the artifacts in the royal tomb date to approximately 317 B.C… a generation after Philip’s assassination at his daughter’s wedding in 336 B.C.

Additionally, Philip II was a great warrior, who bravely battled at the front with his soldiers, something that surely would have brought him plenty of wounds… certainly more than just a cut to the eye. According to several ancient authors, Philip’s right collarbone had been shattered by a lance sometime around 345 B.C., a wound to his right leg in 339 B.C. had left him lame, and one of his arms had been maimed in battle. Unfortunately these scars are nowhere to be seen on the old bones in Aigai.

But then, with all the royalty and pomp found in those deep quiet chambers, whose skeleton is it?

Rather than Philip II, some historians now believe that the tomb actually belongs to Alexander the Great’s half brother, Philip III Arrhidaeus, a considerably less exciting historical figure.

Apparently he too was a king, but in name only, as Philip III may have been physically disabled or mentally ill. Plutarch reported in the second century A.D. that, as a child, Philip III was poisoned by Alexander the Great’s mother, Olympias in an attempted assassination. Alexander the Great was, in fact, second in line to the throne – after Philip III- and supposedly Olympias wanted to change that. If true, this story may explain why the remains in Aigai show few signs of physical stress, something that is consistent with a person of weak constitution.

There is something else that is special about the bones in that tomb… they are remarkably well preserved. Like, really astonishingly well preserved, completely different from the usual pile of ashes and fragments. There was also (maybe not so coincidentally) something special about Philip III’s funeral. Unlike most kings, whose corpses were set alight on the pyre almost immediately after their last breathe, Philip III’s body wasn’t cremated until a full month after his death. He was assassinated, possibly by Olympias, in 317 B.C. and then buried. Ancient historians report that Philip III’s successor later exhumed, cremated, and re-buried the sickly royal as publicity stunt. The fact that Phillip III’s body was already ‘dried’ could explain why the skeleton is still so complete.

As for the skull damage which supposedly identifies the bones as Philip II (not III)… well, researchers have an answer for that too. Those nicks and bumps could be just normal bone deviations and consequences of the cremation process.

Of course, the facts aren’t all in… and much of the evidence is circumstantial. Why would an inconsequential king have so much treasure and immortal glory? Alternatively, can we claim it’s Philip II when enough clues don’t add up? Indeed, it’s a mystery that might never be fully solved, but that’s not going to stop us from trying...

Thank you Anya! Fascinating

Out mutual past is far more exciting than most of us ever realised.

The Med is where most of our western civilisation once started!