Dear Classical Wisdom Reader,

We clearly have Christianity on the mind... indeed, last week’s “Two Faces of Jesus” E-book was of great interest. Looking at the accepted as well as rejected gospels of Christ shows the history in a very different light - truly a Christmas book like no other!

(Classical Wisdom Members, you can access the ebook here)

But today, we will take a turn from the man himself to his followers: the Latin Christians.

It’s a curious point in history, a Venn diagram between the falling of a great civilization and the birth and extraordinary growth of a religious movement. But what were these early believers like? What was their language, their poetry, their art?

In this month’s Classical Wisdom Litterae Magazine, Members can enjoy a deep dive into this fascinating world. We’ll ask how much the Neoplatonists influenced their beliefs... and the very surprising reason why the Christians were not thrown to the lions... below.

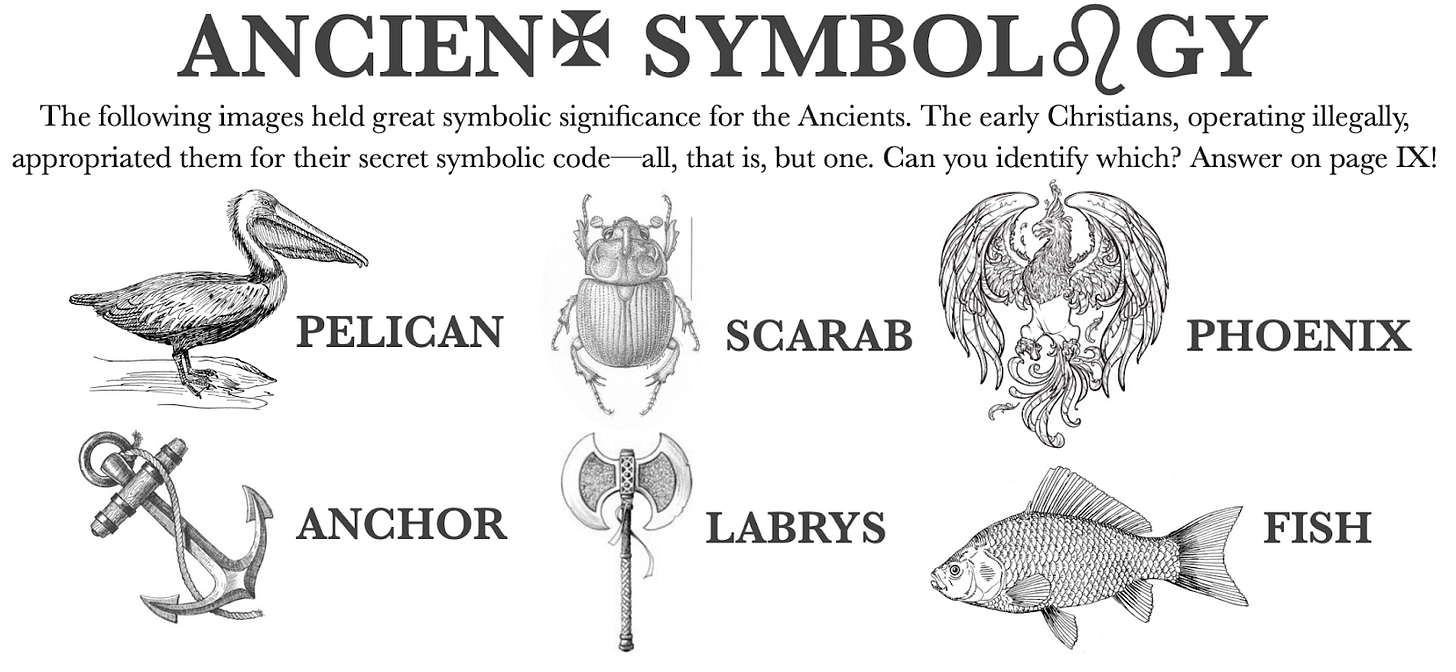

But first, for today’s article, we’ll delve into a world of mystery, symbols and secrets: That of early Christian art. What were the secret codes for the burgeoning cult? Why is it shocking we have their art at all? And what fantastic Christmas decorations will you be inspired to create from this article?

Merry Christmas Peacocks, anyone?

Enjoy!

All the best and a very happy holidays to all!

Anya Leonard

Founder and Director

Classical Wisdom and Classical Wisdom Kids

Mystery, Secret Symbol: Early Christian Art

By Nicole Saldarriaga

Early Christian art is an interesting creature. Not much of it has survived the ravages of time, and what has survived isn’t always actually identifiable as Christian art. In fact, there are some scholars who argue that it’s a miracle early Christian art even exists in the first place.

After all, much of early Christian art (and according to art historians, this early period was relatively long lasting, as it constitutes art produced from the earliest emergence of Christianity to sometime between the years 260 and 525) was produced under somewhat complicated circumstances.

To begin with, Christianity was a highly persecuted religion, its early followers were largely members of the impoverished lower class, and the traditions from which it evolved (that is, the religious traditions of Judaism) frowned upon the production of graven images because of laws against idol worship.

With all of this in mind, it may be prudent to ask: Why did Christian iconography and art even develop in the first place? The answer to this question really boils down to a matter of cultural influence.

Early converts to Christianity were not all from a Jewish background. Many of them had been raised in Greek or Roman societies, in which religious imagery and symbolism were a ritualized part of worship. This deeply ingrained appreciation of images was not so easy to erase, and many early converts looked to incorporate it into their Christian lives as well.

It’s largely because of this cultural mix that elements of Classical Greco-Roman art are so present and identifiable in surviving early Christian art. Artistic media—the fresco, the mosaic, the sculpture, and the illuminated manuscript—is the same in both traditions, and early Christian art exhibits multiple examples of Roman late classical style, such as a proportional portrayal of the body and an impressionistic interpretation of space.

Early Christians even directly borrowed images from Greco-Roman tradition, though of course they assigned new meaning to these previously pagan symbols. For example, the peacock. The peacock was a symbol of immortality in Greek iconography because the Ancient Greeks believed that a peacock’s flesh never decayed, even after death.

Early Christians adopted this symbol of immortality and “tweaked” it slightly—over time the “eyes” on the peacock’s feathers came to symbolize the all-seeing Christian god. The image of a peacock drinking from a vase symbolized a follower of Christ receiving the “waters” of eternal life. The peacock also came to be associated with paradise and was often depicted next to the Tree of Life in the Garden of Eden.

The image of the “Good Shepherd” is another excellent example of image-borrowing. The Greek “kriophoros,” or “ram-bearer,” was a very common image of a young man carrying a lamb across his shoulders. In the Greek tradition, it was meant to commemorate solemn religious sacrifices and eventually became more of a common pastoral vignette.

Early Christians borrowed this image as a symbol of Christ (often referred to as a loving shepherd in both the Old and New Testament texts), but it wasn’t until later centuries that the young man in the image began to be explicitly portrayed as Jesus.

This phenomenon is significant for reasons beyond the obvious cross-cultural influence, of course. As a religion that was highly persecuted in its early stages,

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Classical Wisdom to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.