The Realm of Poseidon: A Mythical Voyage Around the Aegean

By Peter Marshall, Contributing Writer, Ancient Origins

"Poseidon

the great god

I begin to sing, he who moves the earth

and the desolate sea…

You are dark-haired

you are blessed

you have a kind heart.

Help those who sail upon

The sea

In ships."

~Homeric Hymn to Poseidon

Gods and Legends

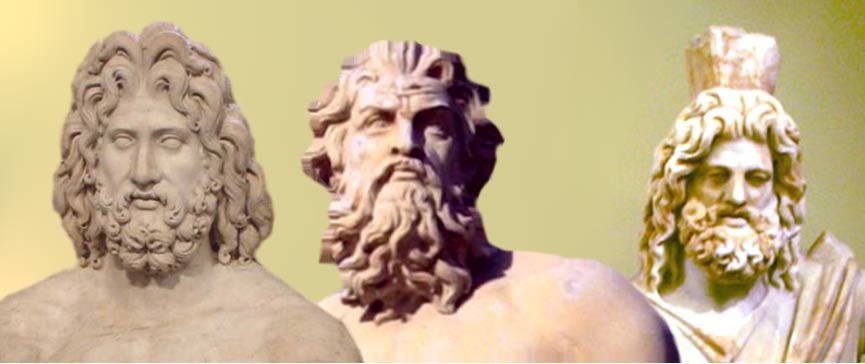

Poseidon was the Greek god of the sea, the shaker of the land responsible for earthquakes, and the god of horses. Usually living in the sea, he could make the waters either calm or stormy depending on his volatile moods. As a patron deity of Athens, Poseidon competed with Athena, who planted the sacred olive tree, by establishing a magical well of salt water on the Acropolis.

If any boat was to survive in Poseidon’s Realm, its crew would have to appease him, usually in the form of sacrifices. The ancient Greeks would kill bulls on beaches or temples and offer up the sacrifices to the god; I preferred in my sailing voyage around the Aegean to make a libation to his memory and presence, usually in the form of the first glass of wine which I poured in the waters of Homer’s ‘wine-dark sea’.

Poseidon—Neptune to the Romans—was one of the three main gods of ancient Greece. He was the brother to Zeus, the most powerful god and ruler of the Heavens, and to Hades, the god of the Underworld where a soul goes to spend a ghostly existence after death. As with the other gods and goddesses, they intervened into human affairs and often took the form of what humans called fate.

When Odysseus, for instance, tried to get home to Ithaca after the Trojan War, Homer tells us in his epic poem The Odyssey, it took him many years because he had angered Poseidon after blinding one of his sons, the one-eyed monster Cyclops Polyphemus for eating his crew and for keeping him captive in a cave. On the other hand, Odysseus was helped on his way by the intervention of the goddess Athena who wanted the Trojans defeated.

The gods and goddesses normally lived on the summit of Mount Olympus (the tallest mountain in Greece, and only climbed by humans at the beginning of the last century, and by myself this century). Although in some ways idealized, they were all-too-human, quarrelling with each other, committing adultery, laughing as well as being downhearted. Zeus would often have arguments with his wife Hera, the goddess of marriage and childbirth, particularly because of his many infidelities.

Despite the cities along the coast of the Eastern Aegean being the birthplace of philosophy and science, with one philosopher saying we can know nothing of the gods and the afterlife, most Greeks firmly believed in their gods. They held Delos in the center of the Aegean to be a sacred island, the birthplace of Apollo, the god of light, music and knowledge, and his twin sister Artemis, the goddess of the hunt and the moon. And they readily consulted oracles, especially at Delphi, in their attempts to see into the future.

But Apollo was also the brother of Dionysius, the god of wine and ecstasy. Many festivals of plays and songs were put on his honour. The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche for one saw the birth of Greek tragedy to a combination of ‘Apollonian’ spirit giving form to ‘Dionysian’ energy.

Aegean Voyage

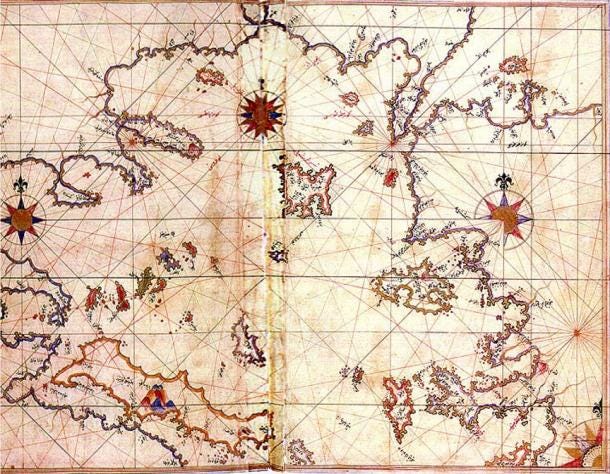

Mythology was an important part of my voyage around the Aegean as it helps to understand ancient Greeks. I set off in a small sailing boat with a traveling companion and traveling at roughly the same speed as the ancient boats, I drew a great circle around the Aegean.

My voyage in space reflected my voyage in time, for I investigated the various stages in ancient Greek history, from the Cycladic, Minoan, Mycenaean, Classical and the Hellenic. I also wanted to test my hunch that Greek civilization cannot be properly understood except from the point of view of the sea. It was central to their lives; Plato described accurately the city states like ‘frogs around a pond’. With a mountainous hinterland and poor soil, they inevitably looked to the sea for foreign trade and new colonies.

The only time they stopped fighting against each other was when they declared a temporary truce for their Olympic games every four years and when they were united against a common foe. Twice they had to face the Persians who had at the time the most powerful empire the world had ever known, under Xerxes I, the ‘King of Kings’. They brought vast armies and huge fleets to conquer the troublesome and squabbling peoples on their western border.

However, believing themselves to be free, the greatly outnumbered Greeks managed to push back the far greater force which would have enslaved them and changed the nature of Europe forever.

After sailing for six seasons in my small sailing boat, covering over 5,000 miles, I visited many ancient sites both famous and obscure and met many Greeks and Turks on the way. I suffered a near shipwreck and sinking. But more than sailing narrative and personal quest, I returned with a remarkable portrayal of the Greeks and a fuller understanding of their history, mythology and culture.

It is certainly worth studying the art, sculpture, literature, philosophy and architecture of ancient Greece—not only because the people are valuable and fascinating in themselves—but because the culture forms the seabed of Western civilization. I have witnessed the unforgettable portrait of arguably the most beautiful and magical sea in the world.

Peter Marshall is the author of Poseidon’s Realm: A Voyage around the Aegean the recently published by Zena. ISBN 9780951106969. He has written 16 books which have been translated into as many languages. His website is www.petermarshall.net