Dear Classical Wisdom Reader,

I usually try to avoid the news, but I find living under rocks a tad uncomfortable and it’s hard to sleep if your head is in the sand. Plus, Pericles’ insight/threat of political intervention usually ends up echoing in my ears.

But here in the US, with the TVs blaring from every waiting room and glaring in most of the restaurants, ignoring the news would be impossible, even if you tried. So of course I heard of Saturday’s assassination attempt on the former US president, Donald Trump.

My first thought was of ancient Rome, the fall of the Republic and the rise of the Empire. It’s a period of history so scarred with assassinations, indeed created by them, that the association needs no explanation. What surprised me, instead, was how previously that aspect of the ancient world felt so unrelatable. It always seemed so extreme and it was hard to imagine how it got to that level of violence... and how everyone at the time was so used to it.

Perhaps it’s not always good to think of the Roman empire...But let’s go back to ancient assassinations and discuss what they were actually like.

While the act (and even attempts) of assassination are absolutely not new, the word itself is a relative newcomer for our timeframe. The term "assassinare" (assassin) was used in Medieval Latin from the mid 13th century... so perhaps it’s not that surprising that the list of ancient assassinations seems so small. With the clear exceptions of remarkable historical incidents like the death of Julius Caesar or the killing of Alexander the Great’s father, Philip II of Macedon, political deaths simply weren’t described as such.

Because what’s the difference, really, between assassination and murder? Think of Mark Anthony soldiers meeting Cicero while he attempted to flee... or poor Pompey the great being decapitated on the Egyptian beach. And in the ancient world, where literally taking off a rival’s head (or indeed the rival of a ‘friend’) was upsettingly common, what do you do with other ‘types’ of take downs, like ‘forced suicide’? From Socrates to Seneca, it was another tactic to remove political dissidents and eliminate pesky gadflies.

Indeed, ancient history is replete with infamous murders and assassinations (as well as attempts) that have left lasting impressions…

We’ll get into today’s Members in-depth article shortly, which delves into the other side of Nero, but first, here are some of the most famous ancient assassinations (and attempts) you can refer to in your next political discussion:

Agamemnon (c. 13th century BC): We are actually going to start with a bit of Greek mythology when Aegisthus murdered Agamemnon, the king of Mycenae, upon his return from the Trojan War. This act, often depicted in various literary works and dramas, including Aeschylus' "Oresteia," led to further tragedies within the House of Atreus... oh and Homer referred to it as well as the tragedians.

Philip II of Macedon (336 BC): Philip II, father of Alexander the Great, was assassinated during the wedding of his daughter Cleopatra. The assassin, Pausanias, a Macedonian noble, was believed to have acted out of personal revenge or political motives.

Julius Caesar (44 BC): “Et tu, Brute!” Julius Caesar, the Roman dictator, was famously assassinated on the Ides of March by a group of Roman senators led by Brutus and Cassius. This event marked a pivotal moment in Roman history, leading to the end of the Roman Republic.

Caligula (41 AD): Caligula, the Roman Emperor known for his tyrannical rule, was assassinated by members of the Praetorian Guard and senators. His erratic behavior and cruelty led to widespread discontent and his eventual assassination.

Domitian (96 AD): Domitian, another Roman Emperor, was assassinated in 96 AD by court officials and members of his own family who perceived him as a tyrant threatening the Senate's authority.

Hipparchus (514 BC): In Athens, Hipparchus, the brother of the tyrant Hippias, was murdered by Harmodius and Aristogeiton. This act, known as the Tyrannicides, was seen as a pivotal moment in the struggle for democracy in Athens.

Sextus Tarquinius (6th century BC): In Roman legend, Sextus Tarquinius was murdered by Lucius Junius Brutus and others, leading to the overthrow of the Roman monarchy and the establishment of the Roman Republic.

Pericles (429 BC): According to ancient sources, including Plutarch and Thucydides, a group of political opponents conspired to assassinate Pericles, the Athenian Statesman and general. Their motivation was likely rooted in political rivalries and disagreements over Athenian foreign policy and internal governance. They were unsuccessful and Pericles lived on… only to die in the plague.

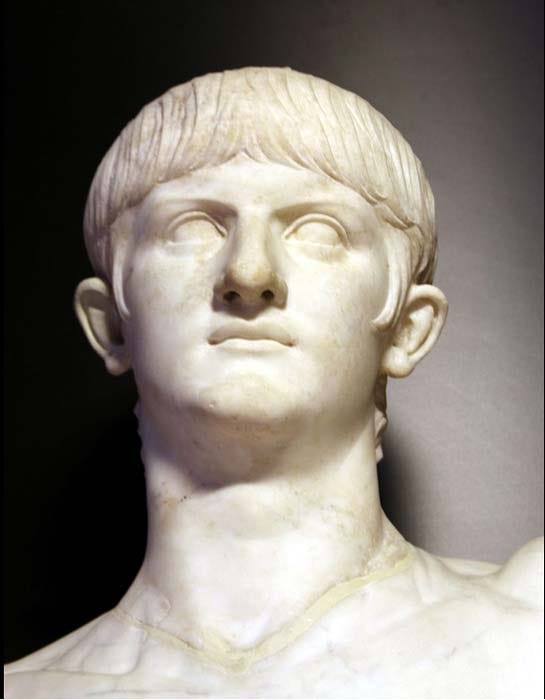

Emperor Nero (68 AD): Several assassination attempts were made on Nero, another Roman Emperor known for his tyrannical rule. These attempts contributed to his paranoia and eventual downfall. His death marked the end of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. There are conflicting historical accounts of how Nero died and to this day it remains unknown if it was by suicide, forced suicide or outright assassination.

Now, the astute reader will observe that there is an over-representation not only of Roman Emperors, but specifically those of the Julio-Claudian Dynasty. Perhaps it was just a time period when such violence was normalized, accepted and expected... or perhaps it was the specific actions of the men in question. After all, Nero is famed for playing the fiddle while Rome burned... right?

Well… like most things (including Nero’s apocryphal fiddle), it’s a little more nuanced than that.

Today’s Members in-depth article takes a serious look at the history of Nero, especially surrounding the fires in the capital and asks if he really was that bad. He certainly wasn’t playing the fiddle (it hadn’t been invented yet), but were his actions in line with his reputation? Read on to discover the other side of Nero.

Classical Wisdom Members, you can delve into the full history of the Julio-Claudian dynasty with our Ebook on the infamous family. It includes The Twelve Caesars by Suetonius, a Roman historian who wrote during the early Imperial Era of the Roman Empire and who was still a young man during Nero’s death. Members can access to the Ebook below the article.

**IF you aren’t a member yet, take this moment to level up your love of the ancient world and enjoy the complete article as well as the ebook. Find out the full story and how understanding our past can help us make sense of our today:

All the best,

Anya Leonard

Founder and Director

Classical Wisdom

The Other Side Of Nero?

By Martini Fisher

For centuries, the Roman emperor Nero has been well chronicled for his cruelty. Stories about his madness include divorcing his first wife before having her beheaded and then bringing her head to Rome for his second wife, having his own mother executed, as well as castrating a former slave before marrying him.

However, despite the numerous charges against him by ancient writers, there are also evidence that Nero enjoyed some level of popular support. “He let slip no opportunity for acts of generosity and mercy, or even for displaying his affability,” wrote the otherwise critical Suetonius. More recently, a poem dated about two centuries after Nero’s death depicts him in an even more a positive light by proclaiming Nero a man “equal to the gods,” suggesting many individuals in the Roman Empire held a favorable view of him long after his death.

After Nero ordered his mother to be executed in 59 CE due to her interference in his personal life and political policies, he is widely portrayed a becoming more of a tyrant, spending excess amounts of government funds on personal indulgences.

It was believed for a long time that Nero started the great fire in 64 CE to make room for his new villa. The impression one is left with from this story is that his mother, Julia Agrippina (Agrippina the Younger), may have been the only steadying influence he had. But is this true?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Classical Wisdom to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.