The Mysteries of The Orphics

By John Mancini, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Of the many belief systems circulating in archaic Greece, Orphism was perhaps the most significant. The state-sanctioned religion of Hellenism may have intermingled with all aspects of daily life, but archaic Greece was also a mixture of superstitious magic and philosophical cults. There were rational beliefs such as Stoicism and Epicureanism, as well as sects with mystical tendencies like Pythagoreanism and later, Orphism, the adherents of which developed the Eleusinian Mystery Festivals, an annual celebration that captivated Athenians for nearly two thousand years.

Unlike the state-sanctioned rituals of Hellenism, of which it was a part, Orphism was guarded by educated elite. Those who followed Orphism were called Orphics, and they held their yearly mystery festival on the Eleusinian plains west of Athens in celebration of Demeter and Persephone – as well as their mysterious consort, Dionysus, who played a key role in this religion.

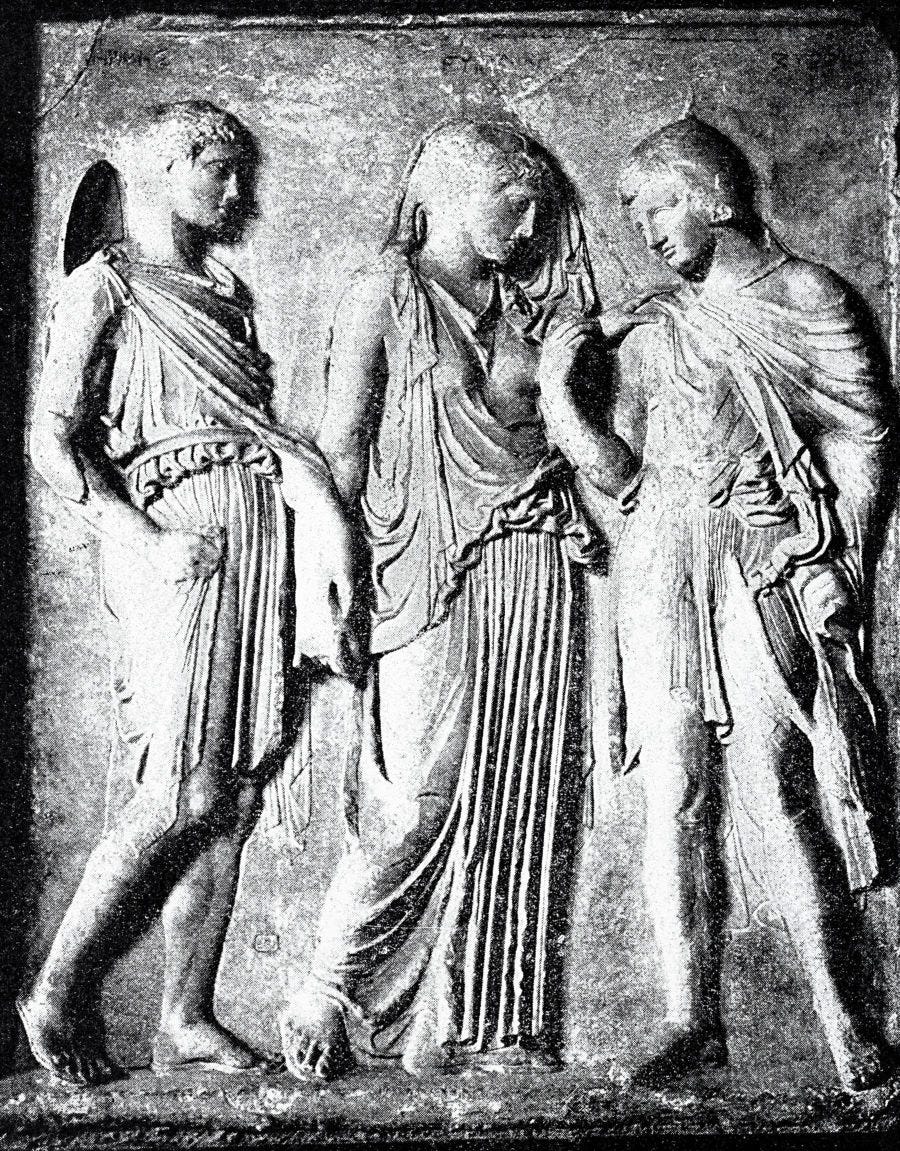

The Orphic religion, as well as their texts, was said to have been associated with the literature from the mythical poet, Orpheus. In the myth of Orpheus, his wife Eurydice suffers a fatal encounter with a snake. By journeying to the Underworld and composing a song that softens the heart of Hades, Orpheus is able to win his wife’s resurrection, but on one condition: he mustn’t turn back to look at her on his way out. Of course, he can’t resist one last look, and he immediately loses his love a second time. From then on, Orpheus can only recall Eurydice’s ghost through song.

There is an unhappy version of the Orpheus myth as told by Aeschylus in the fifth century B.C. Similar to the ending in Ovid’s Metamorphosis, Aeschylus’ play describes Orpheus dismemberment by the Bassarai (the Bacchants in Ovid). However, his head goes on singing and makes its way across the sea to Lesbos where it is venerated by Apollo.

Orpheus’ death in this myth as well as in the Metamorphosis can be seen as an allegory for peaceful societies inevitably succumbing to barbarism. Ovid claims that Dionysus punished the Bacchants for killing Orpheus, but in contrast, Aeschylus’ play has Dionysus sending the Bassarai to punish Orpheus for not paying him tribute. This is an interesting distinction that differentiates Orphism from earlier orgiastic cults. The Orphics were enemies of the orgiastic praise of early Dionysian rituals – and the fundamental point of the Orphic poems was the dismemberment of Dionysus at the hands of the Titans.

In the Orphic verses Dionysus is Zagreus, son of Persephone and Hades/Zeus. Hera convinces the Titans to tear him apart, but Zeus is able to save Dionysus’ heart, and he destroys the Titans with a lightning bolt. From their ashes man is born – hence man’s “Titanic” nature.

Egyptian myths exerted a lot of influence on Greek myths, especially during the 6th century when Greek merchants frequently visited the country. The Greeks would have been aware of the Egyptian Cult of the Dead, which influenced the Cult of Adonis and Dionysus, whose dismemberment at the hands of the Titans also mirrors the Egyptian myth of Osiris. In an ancient epic by Alcmaeonis, Dionysus-Zagreus is equated with the night, thunder and the earth. He is the “highest of all gods.” For Dionysus was originally a god of the Underworld. The Egyptians equated him with Pluto. In fact, Heraclitus said that Hades and Dionysus were one and the same.

So while the cult of Dionysus, which originated in Egypt, was incorporated into the Orphic religion, it also lost some of its earlier vitality and impact. The central rite of Orphism was the animal sacrifice, a symbolic dismembering and eating of Dionysus. This rite is interpreted as a crime in the Orphic myths, in which the Titans are similarly demonized. Like mankind, the Bacchants are equated with the Titans, hence with the principle of evil, and their Dionysian frenzy was condemned by the Orphics.

The unhappy ending of the Orpheus myth is one of vengeance for turning the Maenads into criminals. Dionysus was a god of the Underworld, and Orpheus did not acknowledge him, but rather associated with Apollo-Helios, the sun god.

Orphism was built on old ideas, but the Orphics systematized these ideas in a practical way, creating an organized religion that was powerfully influential, especially to Christian Gnosticism with its emphasis on love.

Orphism’s insistence on freeing the soul from physical bondage was also borrowed by Christianity, and in Orphism we can also find an origin of religious guilt and its resolution through purification rituals conducted by an elite few who claimed they could save people’s souls – which probably influenced other similar religious priesthoods that came later.

Plato may have thought the Orphics were swindlers, but they were very influential. The Orphics’ ultimate triumph was the concretizing of heaven and hell – of delineating good and evil and putting the work of preparing the human soul for death into a fantastically detailed religious practice.