Dear Classical Wisdom Reader,

I type to you today, dear reader, from a high speed train that is currently cutting through the jungled mountains of Laos. It’s a remarkable feat of engineering, smoothly traversing dense forest at 150 km an hour and navigating the cloud draped hills that stand between the capital and the UNESCO-listed city of Luang Prabang.

Those of you who pay close attention to global politics may recognize this route (the Boten-Vientiane Railway) as one of the flagship projects of the “Bridge and Roads Initiative” or BRI. As of earlier this year, more than 140 countries are part of BRI, which represents 75% of the world’s population and more than half the world’s GDP. So, not exactly a small thing...

It’s an ambitious strategy of the Chinese Community Party to assume a greater leadership role in global affairs in accordance with its rising status. In the words of the Xi Jinping administration, it’s a ”bid to enhance regional connectivity and embrace a brighter future.”

The history lovers among you are no doubt connecting the dots between today’s view out the window and the Classical world… and are probably also thinking that there’s more to the project than just bright eyed optimism for the future.

After all, history is filled with ambitious infrastructure projects that enabled trade, enhanced renown as well as exerted control both economically as well as militarily… Indeed, many posit that the state of the roads are a good indicator of the health of the state.

Take for instance Qhapaq Nan, otherwise known as the Main Andean Road. A huge network of roads once used by the mighty Inca Empire that extends over more than 30,000 kilometers, it was the backbone of the Inca Empire’s political and economic power, connecting production, administrative, and ceremonial centers of pre-Inca Andean culture. The Incas of Cuzco achieved this unique infrastructure on a grand scale in less than a century, extending their vast network across what is now Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru.

But whether they are the famed ports and maritime routes or the brick and mortar roads and bridges, surely none are as famed as the paths carved out by the Romans.

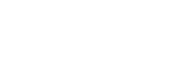

About 1.7 million square miles of territory was covered by the Roman roads, which were made with gravel, dirt, and bricks made from granite and hard lava. Indeed, at its peak the Roman roads covered 400,000 kilometers (250,000 miles) of roads, of which over 80,500 kilometers (50,000 mi) were stone-paved. Moreover, it stretched from modern day Scotland to Egypt, Morocco to Iraq.

It allowed both goods and troops to cross entire nations in a matter of days, as one of my favorite interactive maps of the ancient world (the Orbis Project) clearly indicates.

But just having the idea of connecting point A to point B isn’t sufficient… It's the engineering and technology employed that really make the difference and ensure the desired result.

So today, we will look at the literal foundation of the once mighty Roman Empire… how did they lay the bricks that would last thousands of years? Why were Roman roads so special?

Read on below to discover one of the ancient world’s greatest legacies.

All the best,

Anya Leonard

Founder and Director

Classical Wisdom

P.S. “But who will build the roads?” Is almost always one of the first questions that arise when discussing the need -or lack thereof- of the State. While no doubt the largest infrastructure projects in the past have been executed by powerful nations… is this the only option? Or the best one? Do we need big government for the bridges, roads, trains and planes? Comment below and join the great conversation.

The Many Roads to Rome

By Wu Mingren

The Romans were renowned as great engineers and this is evident in the many structures that they left behind. One particular type of construction that the Romans were famous for is their roads. It was these roads, which the Romans called viae, that enabled them to build and maintain their empire. How did they create this infrastructure that has withstood the passing of time better than most its modern counterparts?

Roads of All Kinds

It has been calculated that the network of Roman roads covered a distance of over 400,000 km (248,548.47 miles), with more than 120,000 km (74,564.54 miles) of this being of the type known as ‘public roads’. Spreading across the Romans’ vast empire from Great Britain in the north to Morocco in the south, and from Portugal in the west to Iraq in the East, they allowed people and goods to travel quickly from one part of the empire to another.

The Romans classified their roads into several types. The most important of these were the viae publicae (public roads), followed by the viae militares (military roads), then the actus (local roads), and finally the privatae (private roads). The first of these were the widest, and reached up to 12 meters (39.37 ft.) in width. Military roads were maintained by the army, and private roads were built by individual landowners.

Constructing Roads to Last

There was no ‘one-size-fits-all’ Roman technique for building roads. Their construction varied depending on the terrain and the local building materials that were available. For example, different solutions were required to build roads over marshy areas and steep ground. Nevertheless, there are certain standard rules that were followed.

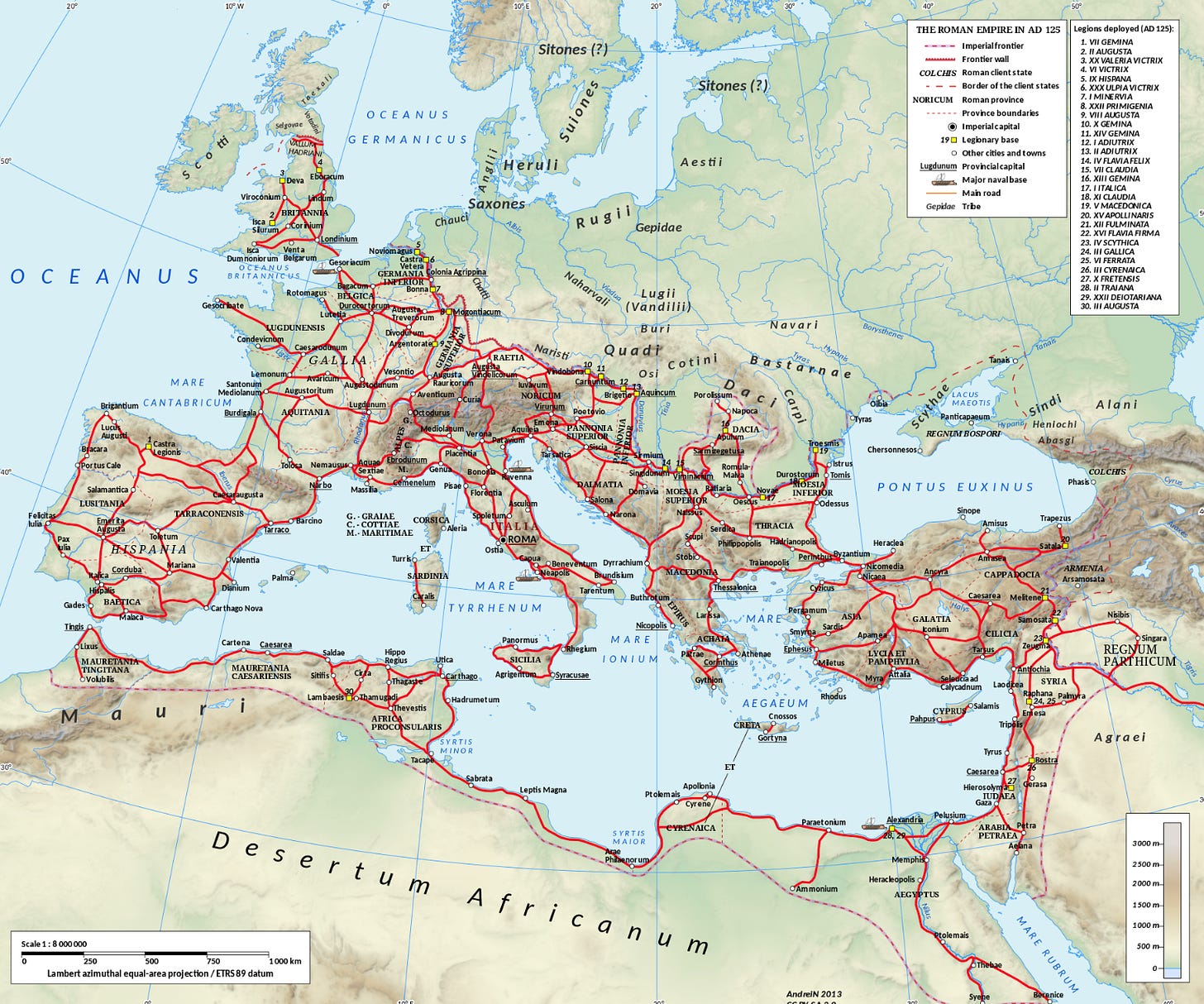

Roman roads consisted of three layers – a foundation layer on the bottom, a middle layer, and a surface layer on the top. The foundation layer often consisted of stones or earth. Other materials used to form this layer included: rough gravel, crushed bricks, clay material, and even piles of wood when roads were being built over swampy areas. The following layer would be composed of softer materials such as sand or fine gravel. This layer may have been formed by several successive layers.

Finally, the surface was made using gravel, which was occasionally mixed with lime. For more prominent areas, such as those close to cities, roads were made more impressive by having the surface layer built using blocks of stone (which depended on the local material available, and may have consisted of volcanic tuff, limestone, basalt, etc.) or cobbles. The center of the road sloped to the sides to allow water to drain off the surface into drainage ditches. These ditches also served to define the road in areas where enemies could use the surrounding terrain for ambushes.

Pathways to Trade and Cultural Exchange

Roads played a crucial role in the Roman Empire. For a start, the roads allowed people and goods to move swiftly across the empire. For example, in 9 BC, using these roads, the future emperor Tiberius was able to travel almost 350 km (217.48 miles) in 24 hours to be by the side of his dying brother, Drusus. This also meant that Roman troops could be deployed rapidly to various parts of the empire in the event of an emergency, i.e. internal revolts or external threats. Apart from allowing the Roman army to outmaneuver their enemies, the existence of these roads also reduced the need for large and costly garrisons throughout the empire.

In addition to serving a military purpose, the roads constructed by the Romans also enabled trade and cultural exchange to occur. The via Traiana Nova (known before that as the via Regia), for instance, was built on an ancient trade route that connected Egypt and Syria, and it continued serving this purpose during the Roman period. One of the factors that allowed such roads to facilitate trade is the fact that they were patrolled by the Roman army, which meant that merchants were protected from bandits and highwaymen.

Another function of roads in the Roman world is perhaps an ideological one. These roads may be interpreted as a mark left by the Romans in the landscape, signifying their conquest of the terrain and the local population.

My back hurts just thinking about the amount rock moved for the Roman roads. I would have preferred the Chinese silk road using rammed earth.

China in 2024 has learned a lot from history…

They have a lot of ‘labourers’ sent out as part of their Belt & Road construction projects whom often become ‘citizens’ of the countries they ave been sent to. A current version of colonisation such as England and its development of Terra Australis…

Sydney’s early roads not as great as Romans built by Brit convicts !

‘The settlement of Sydney was established in 1788, when Arthur Phillip led the 11 ships of the First Fleet into Port Jackson. The settlement that sprung up around Sydney Cove was a convict colony, ruled by governors appointed by London.’