Dear Classical Wisdom Readers,

As history unfolds in front of us, it can be difficult to take stock of what is happening. This is what we greatly appreciate about studying the ancient world, of course… it enables us an essential perspective, a 10,000 foot view or a 5,000 year span.

It is for that reason, I have been dedicating the last few mailbags to the issues at hand. Asking, “Can we be humane in the face of horror?”, “Have we become Anti-human?” and “How should we treat our enemies?”

I’ve sincerely enjoyed the thoughtful and thought-provoking responses you and your fellow Classical Wisdom Readers have submitted on these hot button topics. Practicing and acknowledging our ability to have civil discourse in these times is absolutely critical.

Thank you.

I have more replies to offer up… but today I thought I would tack a different course and let one of the ancients speak on this both current and timeless issue.

So I will cede the floor, if you will, to Seneca. How did the Roman Stoic philosopher address the Emperor Nero? What was his advice on how to treat his foes?

Read on below…

And feel free to add your own comments afterwards… or write to me at anya@classicalwisdom.com and I will publish our remaining replies next week.

All the best,

Anya Leonard

Founder and Director

Classical Wisdom

P.S. How has the portrayal of Nero been shaped throughout the ages?

Classical Wisdom Members can enjoy a founding text -one of the first novels written- the Satyricon by Gaius Petronius Arbiter in the 1st century AD during the reign of the emperor Nero.

It gives a scathing, exhilarating, lubricious, grotesque, and imaginative inside peek into Nero and his extravagant court.

Members can enjoy this subversive and picturesque novel here:

Seneca On Clemency: A Letter To Emperor Nero

By Van Bryan

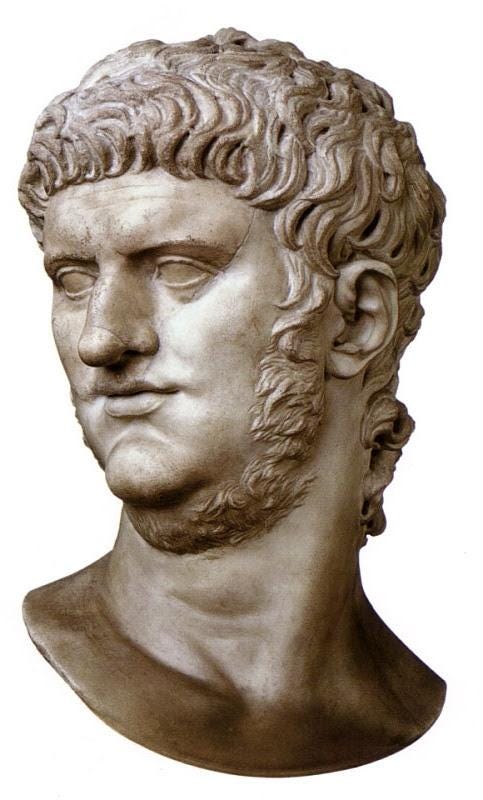

On Clemency was written by Seneca and addressed to Nero not long after his 18th birthday- you know, before things got all murdery. It includes much praise for the young emperor who had accepted control of the vast empire at the tender age of seventeen. It includes sound advice and makes an appealing case for the benefits of compassion and clemency for a budding young ruler.

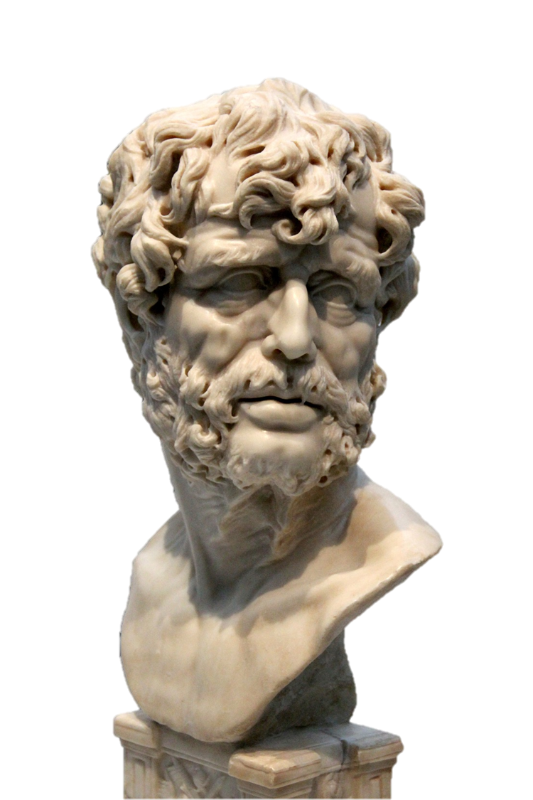

But before we can gain any wisdom from Seneca's On Clemency, it would help if we had a better understanding of the philosopher himself and his motivations behind writing this letter. Seneca the younger (named after his father) was an ancient Roman philosopher, statesman, dramatist, and most importantly, a tutor to the young Emperor Nero. Seneca is often regarded as being the most prominent of the Roman stoic philosophers and is second only to the original founder of Stoicism, Zeno of Citium.

While an in-depth explanation of stoic philosophy is out of the question for the purposes of this essay, a brief summary of Stoicism is certainly in order.

The Stoics believed that the universe was elegantly designed with purpose and that all of nature is conducted with reason and logic. The stoics believed that this meaningful design within the universe was literally the material manifestation of God. Our world is not consumed by chaos, but it is expertly guided by divine law, and it is governed by the rigorous necessity of cause and effect. Since the universe adheres strictly to the logical doctrine of cause and effect it can be said that anything that happens is a result of necessity and part of a purposeful plan.

The implication of this is that human free will is an illusion. Humans are inescapably a part of the universe and are therefore subject to an infinite causal chain in which each event necessarily follows from the preceding causes. Though we may believe we choose to do one thing or another, in truth we are merely assenting to do what we must inevitably do.

The stoic's ethical philosophy can be summed up by the expression "live according to nature." This means two things. First, we ought to live our lives by consciously adhering to the divine law of the universe that admits no exceptions. Secondly, we should act with absolute reason, as the Stoics believed that reason was the truest nature of a human being. Since nature is governed by God, and God is the manifestation of reason, the only truly virtuous life is one adhering to absolute reason.

The Stoics teach us to consciously accept the divine law of nature and adhere to it as best we can. A person should not pursue pleasure but instead pursue wisdom for the sake of duty. Poverty, disease, famine, war, and death are all part of the divine law of the universe, and we should regard these things with absolute indifference. A stifling of man's desires for physical goods or pleasure was a key aspect of stoic ethical philosophy. This is where we get our modern understanding of the word "stoic", as in "the man resigned himself stoically to the impending traffic jam."

The stoics did not intend their philosophy to merely be interesting food for thought. They attempted to ignite an ethical revolution that would replace the self-destructive practices of self-indulgence and pleasure-seeking with the dutiful ideas of Stoicism. They did this partly by attempting to influence the key political players of the Roman Empire. And in this regard, Seneca was well placed as the tutor and eventually the adviser of Emperor Nero.

On Clemency begins by examining the relationship between a ruler and the state, and by extension, the people. Seneca encourages Nero to consider himself a servant to the public good, rather than being superior to those he rules over. The philosopher compares the relationship of a ruler and his people to the relationship between a soul and a body. Seneca suggests that the purpose of a soul is to adhere to reason and to use logic for the betterment of the body. Similarly, the ruler of a populace is meant to exert reason and compassion, and subsequently guide his people to peace and prosperity.

"This enormous populace which is the shell for the soul of one man is regulated by his spirit and guided by his reason; if it were not propped by his intelligence it would bruise itself by its own strength and crumble to fragments." -Seneca (On Clemency)

Seneca continues by saying that it is within any man to take life. Any commoner can kill and any man can die. Even great emperors can die. The truest mark of magnanimity is the ability to give life, to pardon transgressions and allow villains to reform. For only someone who is higher than a commoner, someone like an emperor can grant life just as easily as he could take it. Acts of mercy, when acts of violence are just as accessible, speak greatly to the character of a man. It shows that a ruler's true dedication is to virtue for the sake of virtue, and it proves that the king is for his subjects just as much as he is above them.

An example of clemency in a ruler can be seen within Nero's own family. Seneca speaks of Emperor Augustus who, as a young man, resorted to violence against friends and conspired against the consul Mark Anthony. However, as an old ruler, Augustus saw that a life of violence only begets more violence. When he was forty years old, Augustus learned of an assassination conspiracy devised by the man Lucius Cinna. Rather than kill Lucius, Augustus granted the man a pardon and allowed him to live out his life unharmed.

Seneca points to the clemency of Augustus as the reason why he was so loved by the people, and why he was able to rule the empire until the day of his death in 14 CE.

"It was his (Augustus') clemency that carried him through to safety and security, it was this clemency that made him welcome and beloved though the Romans were not used to the yoke when he laid his hands upon them, it is this clemency which to this day assures him a reputation which even living rulers can scarcely match"

-Seneca (On Clemency)

Seneca then compares the compassion of Augustus with the cruelty of the dictator Lucius Sulla, a man who, according to Seneca, only stopped slaughtering civilians when it became clear that he had no more enemies to kill. Seneca reports that Sulla ordered the execution of 7,000 Roman citizens during his time as a ruler. It was said that the screams of the thousands being butchered were so loud that it could be heard by the senators while they were in session. Sulla would dismiss the senator’s unease by declaring...

"Let us attend to our business, my lords; it is only a handful of subversives who are being executed at my order."

With these two comparisons in mind, Seneca concludes that the mark of a just ruler is compassion and mercy, while the quality of a tyrant is a penchant for willful murder. Seneca continues by saying that it is no surprise that the former tend to live long and happily, while the latter all too often succumbs to revolution or assassination.

While mercy and clemency are indeed the marks of a just ruler, that does not mean that an emperor will never have to get his hands dirty. Seneca admits that there are certainly instances where criminals must be punished, even put to death for their crimes. The responsibility of the ruler should be to his people. And just as a doctor might amputate a gangrenous limb, so too must a king do away with men who would attempt to harm the populace. This emphasis on execution as solely a means to improve the populace is well noted by Seneca. It would be far too easy for a monarch to kill for personal, vindictive reasons; and then we would find that man slowly sinking into the dark waters of tyranny.

Seneca states, again and again, his belief that clemency and mercy will produce trust and even love between a ruler and his subjects. Willful killing, on the other hand, will never benefit a king, but instead create for him more and more enemies.

"To save men in crowds and in the exercise of duty is a godlike power; to kill in multitudes and without discrimination is the power of fire and ruin"

-Seneca (On Clemency)

Seneca's advice to the young Emperor Nero substantiates itself as sound wisdom that is supported by the dutiful philosophy of Stoicism. But as you may already know, Nero did not take much of the advice to heart. Nero as an emperor is often remembered for the brutal executions of his mother, Agrippina, and first wife, Octavia. Many historians also believe that Nero was responsible for the poisoning of his stepbrother, Britannicus.

It is also believed that Nero may have been responsible for the great fire of Rome in 64 CE. The fire destroyed three of the fourteen Roman districts. The rubble was then cleared away so that Nero could build his extravagant palatial complex. It was rumored (though not substantiated) that while the fire ravaged the city, Nero stood on his balcony watching the flames, playing the lyre, and singing to himself.

Nero's time as a ruler would come to an end in June 68 CE. His own Senate had declared him a public enemy. They intended to capture Nero and execute him by public beating. Fearing for his life, Nero fled Rome and hid away in a small villa several miles from the city. There he committed suicide. The first emperor to ever take his own life, the death of Nero would mark the end of the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

A modern reader who reads "On Clemency" would undoubtedly find it ironic that Seneca would preach virtue, mercy, and compassion to a man who would only be remembered for murder, extravagance, and madness. The voice of Seneca within the text appears hopeful, even optimistic. He presents sound advice to an emperor at the dawn of his reign. It was advice that would, unfortunately, fall on deaf ears.

A very timely post, thank you!

Thank you for this enjoyable piece. A true justice is required for right mercy. That is where Nero, et al, and we Americans, have erred. Most times when it doesn’t work, justice is driven by the self interest of those leaders; that becomes their (false) justice superseding their actual charge of justice: of the good of the people, all the people. I can understand politicians vilifying each other (much as I wish it were not so), but when they publicly vilify half the population (and both sides do it as do their constituents), I fear mercy is about as probable as with Nero. We all should,but with Nero won’t, heed Seneca’s wisdom.