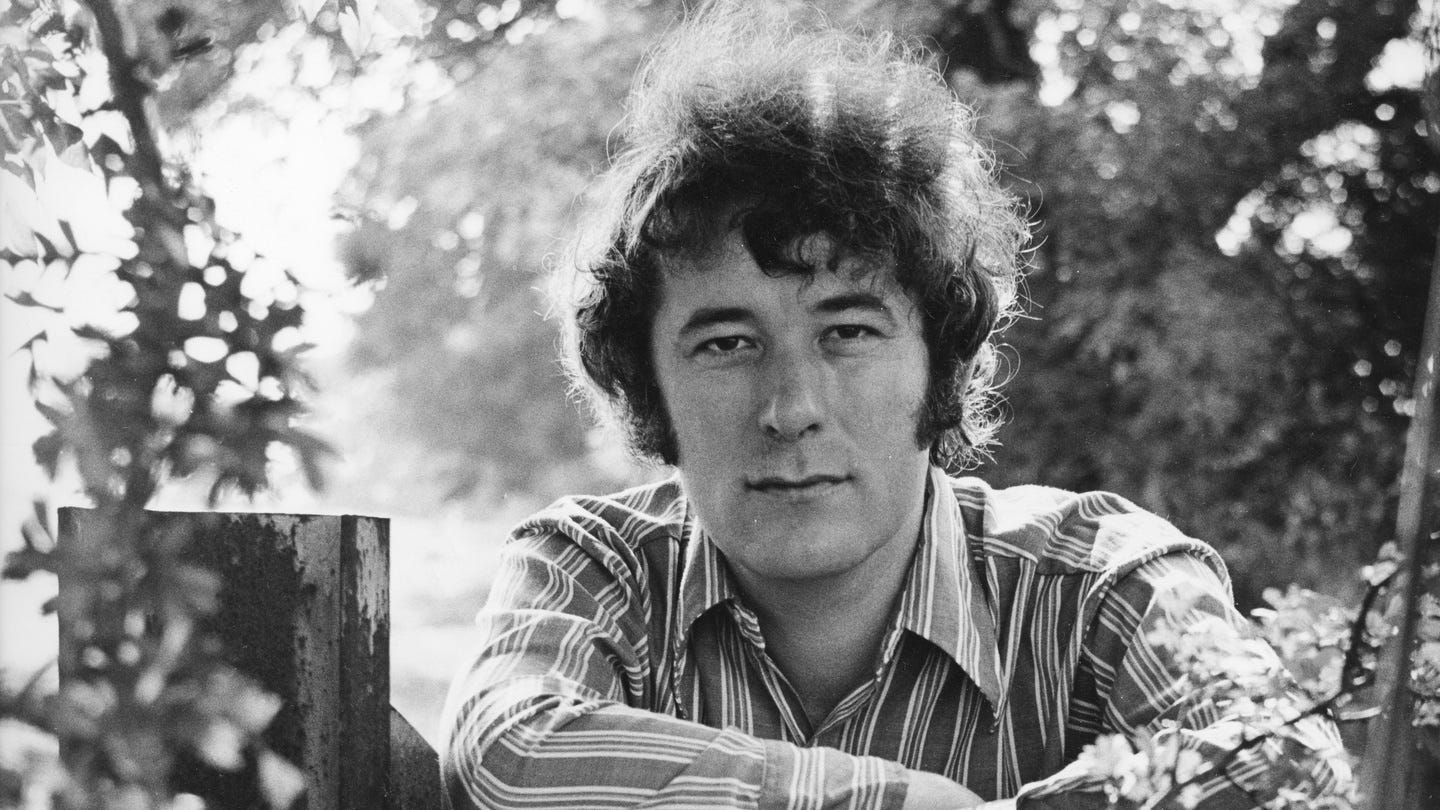

Seamus Heaney

A Lifetime of Ancient Poetry

Dear Classical Wisdom Reader,

As the year comes to an end, and people rush home for Christmas, I thought we’d do something a little bit different today…

We’re taking a tiny step out of the ancient world itself and looking at one of the many, many ways it has come down to us: through the work of acclaimed poet and Nobel Prize winner Seamus Heaney.

Here in Ireland (and further afield) his legacy is enormous. More importantly for our purposes here at Classical Wisdom, much of his work was influenced by the poetry and culture of ancient Greece and Rome. As this year marked the 10th anniversary of his death, I thought it would be a good time to have a look at how ancient literature shaped one of the giants of modern poetry.

I hope you enjoy it. And I also hope you have a great time over the holidays!

All the best,

Sean Kelly

Managing Editor

Classical Wisdom

P.S. If you’re interested in learning more about Irish literature (past and present!) be sure to check out my own substack project HeavenTree, which will be (fittingly) returning to life early in the new year.

And don’t worry, both myself and Classical Wisdom will still be right here every week, bringing you ancient wisdom for modern minds!

Seamus Heaney and the Classics

by Sean Kelly, Managing Editor, Classical Wisdom

Seamus Heaney was in Pylos, the land of ancient Greece’s Nestor and the very landscape of Homer, when he discovered he had won the Nobel Prize. It was his first time to visit the country: at the age of 56, he had finally gone on a “much delayed” trip to Greece, whenever his son asked over the phone if he had heard the news. It was a strange, fitting coincidence considering that so much of his work has its roots in the literature of the ancients. Yet his journey began far away from such landscapes.

Seamus Heaney was born in Bellaghy in Co. Derry in Northern Ireland. His rural background seemingly laid out a life of work on the family farm for him, but early educational opportunities substantially altered this path. He attended St Columb’s College in Derry; here he received Latin lessons which introduced him to the poetry of Virgil, who was to be a massively influential figure in his poetic life. After studying at Queen’s University in Belfast, he became the rare example of a modern poet to shoot to fame from his earliest works.

His early poem ‘Digging’, opening his debut volume Death of a Naturalist, illustrates the two pathways his life could have taken. He compares the shovels of his father and grandfather to a poet’s pen and concludes ‘I’ll dig with this.’ Yet while farm work and the poet’s desk may seem worlds apart, to Heaney that wasn’t the case. His early agricultural poetry has its roots in Hesiod’s ‘Works and Days’, a work which, like Heaney, doesn’t shy away from the physicality and difficulty of rural life, but nevertheless finds a dignity and nobility within it.

Of course, it is impossible to talk about Seamus Heaney without mentioning the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Heaney’s lifetime was contemporaneous with the outbreak of the three-decade long conflict, and to many, he became a key voice of the era. The nature and scale of the Troubles was complex and daunting, yet the ancient world granted Heaney a vocabulary and a paradigm through which to discuss the events of the Troubles, much as it had also done so for his farming life. While poems such as ‘Digging’ are descendants of Hesiod, when it came to the complexities of the conflict, the ancient world would once again grant Heaney a pathway. This time, however, he drew inspiration from Homer, the tragedians, and Virgil.

In his poem “Whatever You Say, Say Nothing” (which lent the title of the recent acclaimed history of the Troubles by Patrick Radden Keefe, Say Nothing) Heaney includes the line “Of the wee six, I sing”. This, of course, references the famous opening line of the Aeneid: ‘Of arms and the man I sing’. The ‘wee six’ being the six counties of Ireland that constitute Northern Ireland, Heaney’s home and primary material for his work. This juxtaposition of the Classical and the contemporary, of myth and brutal reality, encapsulates the paranoia and darkness of living in such a violent time. Elsewhere in the same poem he invokes the Trojan Horse as he writes:

Of open minds as open as a trap,

Where tongues lie coiled, as under flames lie wicks,

Where half of us, as in a wooden horse

Were cabin'd and confined like wily Greeks,

Besieged within the siege, whispering morse.

Heaney was not alone in finding the literature of ancient Greece (and particularly the Trojan War) a suitable lexicon through which to speak about the most vital of contemporary events. Seamus Heaney’s friend and fellow Northern Ireland poet Michael Longley wrote the poem ‘Ceasefire’, just as the IRA ceasefire of 1995 was announced. It takes its inspiration from Alexander Pope’s translation of the Iliad, presenting a key moment of the Greek epic translated into rhyming couplets:

'I get down on my knees and do what must be done

And kiss Achilles' hand, the killer of my son.'

As well as his poetry, Seamus Heaney was also a translator. It was common during the Troubles for various Greek tragedies to be staged. Ancient literature became a way to discuss vital contemporary events. Multiple versions of Sophocles’ Antigone were staged in Northern Ireland during the Troubles, directly linking the central tensions of the play to conflict surrounding it.

Yet the first major work of Classical translation that Heaney produced was his version of Sophocles’ Philoctetes, which he presented under the title of The Cure at Troy. This was initially staged in 1995, and by the time that Heaney produced this work, there was already a long standing tradition of Greek tragedy productions in Northern Ireland. Tragedy presented itself as an evergreen literary form. Throughout the Troubles, Greek tragedy often found potent resonance with contemporary events, often with little or even nothing being changed.

Heaney’s The Cure At Troy is then both part of a local, more contemporary tradition and a broader one with obviously ancient roots. The Cure at Troy tells the story of the wounded Philoctetes in the aftermath of the Trojan War. Whereas it is perhaps not as famous as some of the other works in the corpus of Greek Tragedy, such as Oedipus Rex or Medea, it is nevertheless a powerful work.

The tale of warriors coming to reconciliation held a particular resonance at this moment of time. By 1995, the IRA ceasefire had taken place, and the Troubles were entering their final years. The end of the conflict was potentially in sight. It is in the closing lines of The Cure at Troy that we find some of the most famous and celebrated lines of Heaney’s entire oeuvre. They are not directly translated from the Greek, but rather speak to the spirit of the play, and the times Heaney was writing in.

History says, Don't hope

On this side of the grave.

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed-for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up,

And hope and history rhyme.

It would be almost a decade before Heaney would return again to the world of Greek tragedy. By the time Heaney revisited Sophocles, some years had passed since the Good Friday Agreement had in essence marked an end to the Troubles. Yet all was not well in the world. The intervening years had seen a significant global shift with the events of 9/11.

In 2004, Heaney was commissioned to mark the 100th anniversary of Dublin’s famed Abbey Theatre, founded by fellow Nobel Laureate W.B. Yeats. For the occasion, Heaney returned to Sophocles, this time Antigone, presented under the title The Burial at Thebes.

While there is still obviously a local element to the work, Heaney’s interest had moved abroad. The Burial at Thebes was presented as a meditation on the major international headlines of the day, particularly the war in Iraq. Heaney presents Creon as a Bush figure, unbending to the voices of others, and leading straight into disaster.

The final work of Seamus Heaney’s to be completed was his version of Book VI of the Aeneid. In many ways, nothing else could have been more fitting. It was published posthumously in 2016, three years after Heaney’s death in 2013. Aeneid VI is a katabasis or ‘descent below’, a common feature of Epic poetry, charting Virgil’s descent to the underworld. There, he encounters various figures from his past, such as his former lover Dido, and his father Anchises, all of whom are now dead.

The sequence is, of course, modeled by Virgil after a similar section in Book XI of the Odyssey, wherein Odysseus also descends into the underworld.

Here the personal and the poetic collide once more. In a preface, Heaney reflects on some of his earliest literary experiences. He introduces his final work by recalling learning Latin and translating Virgil at St Columb’s College in Derry. So Aeneid VI is both a beginning and an ending, much as it is for Aeneas himself.

It’s a curious coincidence that the arc of these focuses across his lifetime – from the earlier agricultural poetry influenced by Hesiod, through to the translations of Greek tragedy, and finally the works of Virgil – form a chronological overview in miniature of literature in the ancient world. Through the eyes and voices of the ancients, he was able to see and speak of his own time more clearly.

Like Joyce’s Ulysses, Heaney’s work is another example of how the poetry of the ancient world has spoken again and again across the history of Ireland, and the history of the world.

Virgil's descent into Hell would be mirrored in Dante Aligheri's "Inferno", where Virgil is employed by Dante as his guide.

Wonderful reminder of a time and place in history. Thanks, Seamus.