Dear Classical Wisdom Reader,

On the first day of my husband’s (then boyfriend’s) new job as a journalist, he got to interview George Clooney. The year was 2007 and we had just moved to Dubai in hopes of finding professional work and adventure... of which we found both.

It wasn't one-on-one with the famed actor, but in a bustling press room and “Gorgeous George” as my husband jokingly calls him, was coming through town to promote some of his recent films. When it came to question time, my partner raised his hand and diligently asked a serious question about human rights issues in the middle east, the location of filming. Always a professional, George politely demurred... but dear husband didn’t take the hint. Tenacious as always, he doubled down on the question, only to be artfully diverted and ignored.

Nothing came of it, it was his first day after all... but he was made to know that it wasn’t an okay line of questioning. In fact, there were many such directions of inquiry that were out of bounds and numerous rules, none written, about what could and could not be said.

Alas and to no surprise to those who know my husband, the lesson was not learned... or more likely ignored. A year and half later, we made a hasty (though fortunately preventive) departure from the country. The unwritten rules had become codified and some folks (husband included) just don't know how not to push the limits.

Of course there are many such persons throughout history, who like to poke the bear and bother the powerful. Whether it’s for political reasons or for controversial artistic ends, what happens to these people -if they are allowed to flourish or flounder- regularly changes the course of history.

The Roman poet Ovid, for example, was one such man - though his purposes seemed to be out of an outrageous dedication to art... or at least the risqué. Popular during Augustus’ reign, and particularly during the emperor’s controversial Lex Julia, the Julian marriage laws of 18 BC, Ovid fell afoul of those in power and suffered the consequences.

But what was exactly his offense? Was he in the right... or simply rude? Today’s guest column, by Michael Fontaine, Professor of Classics at Cornell University, looks at the original text of Ovid’s “Manifesto” (along with helpful explanations) to understand a bit more the nature of his banishment.

It sparks interesting questions, such as was his exile justified? Should there be limits on the decency of artists and authors? Or should free speech - explicit or not - override?

Read on below and add in the comments your own thoughts on the topic.

**Please note: You can enjoy today’s article as a prelude to our exciting event, taking place on Thursday, September 26th at noon EST.

We’ll discuss Socrates, Aristophanes, propaganda and clever workarounds, Ovid and early Christians and how this all relates to the very important topic at hand: Free Speech VS Censorship.

Check out the schedule and fantastic lineup, including Professor Michael Fontaine, here:

I hope you can join us!

All the best,

Anya Leonard

Founder and Director

Classical Wisdom

On the Obscenity of Ovid

By Michael Fontaine

Begone! In 8 CE the Emperor Augustus kicked the poet Ovid out of Rome and “relegated” him to a remote town on the Black Sea. Ovid died there a decade later, having solaced his despair by composing Tristia (Sorrows) and Epistulae ex Ponto (Letters from Pontus) to voice his isolation and longing to return.

Centuries later, John Milton regarded Ovid’s banishment as the beginning of the end for free expression in Europe:

“From hence we shall meet with little else but tyranny in the Roman Empire, that we may not marvell, if not so often bad, as good Books were silenc’t.”

What did Ovid do?

Nobody knows. Ovid’s poetry is the only real source of information about his fate, and he himself blamed it on a carmen et error (“a poem and a mistake”).

The mistake could have been literally anything because he never tells us what it was. But he implies pretty strongly that the poem in question was his Ars Amatoria—in English, The Art of Love.

For Ovid, see, Rome was the city of romance. Romeos were everywhere, and so were Rome-grown beauties. Posing as a “professor of love,” therefore, Ovid semi-seriously purported to teach his readers “rules” for seducing the opposite sex—as if women are all interchangeable and their responses guaranteed.

Not very nice!

That could be why the Emperor got so angry. Like several tech titans today, Augustus was concerned about family formation and falling birthrates. A how-to manual for Pickup Artists doesn’t help that.

But maybe there’s more.

In the year 1 CE, Ovid had published a sequel, titled Remedies for Love. The idea here is how to fall out of love, to break an attachment and get over unrequited feelings, and Ovid has 38 recommendations to help with that. Some are sensible, others daring, a few bizarre, and several downright evil. For example, Ovid writes:

Now, since love must be totally banished and out of the picture, let’s talk sex. I’ll explain what you should do in the act. Many ideas I’m embarrassed to say explicitly, so use your brain and infer more than I’m saying in words….

…So then, when sex (because that’s what young people do) is requested, once it’s starting to get close to the time for your date, so that enjoying your lady won’t hook and entrap you, because your body feels ready to burst,

go hump a random girl first.

Pretty offensive, eh? Obscene, even. Would you want your kids reading this?

Augustus must have had steam coming out of his ears.

Yet interestingly, at this very point Ovid interrupts himself to insist the obscenity is deliberate—that it’s part of his “art.” He inserts a digression right where I’ve added those points of suspension to defend his art against charges of obscenity. Have a look:

“The Artist’s Manifesto”

(Ovid, Remedies for Love 357-398)

…Recently, see, some people took issue with books that I’ve published. These censorious souls say that my music’s “obscene” (quorum censurā Musa proterva mea est).

Well, while I’m winning applause—while my praises are ringing out worldwide—fine. Let a critic or two carp at my work if they want!

Envious slander maligns the genius of Homer—our greatest! Every last “zoilus” is named for that first one of all.

Blasphemous cynics have even savaged the poems of Virgil—Virgil!—whose leadership saw Troy bring her gods here to Rome.

Envy targets the tops. Winds bluster and howl at the summits. Lightning targets the tops, fired by Jupiter’s hand!

Look, whoever you are that’s upset at my freewheeling spirit: Think! — if you can — and take poetry into account:

Legends of war enjoy being sung in the meter of Homer. How could heroic verse domicile sexcapades there?

Tragedy’s tone is stately; wrath belongs in its raiments,

whereas for sitcom scenes, comfortable flip-flops are right.

Freedom of speech needs iambs unholstered to fight back an army—strafing consistently, or misfiring every sixth round.

[Note by Fontaine: Iambic verse, which is used for invective, came in two varieties: the “pure” iambic trimeter and the “limping” variety, the latter of which unexpectedly “drags” out every sixth foot.]

Elegy’s silky strains should sing of romantic relationships: she’s a flirty girl(friend); so, let her flirt as she likes.

So,

Achilles does not belong in the meter I’m using, and

Cydippe’s all wrong, Homer, for your epic verse.

No one would tolerate Thais playing the part of Andromache.

Andromache played Thais-like would be absurd.

[Note by Fontaine: Andromache is the legendary widow of Hector, greatest of the Trojan heroes. Thais was a real courtesan of 4th c. Athens who, like Marilyn Monroe, passed into legend herself. Her name eventually became a byword for a glamorous, unabashed, and hypersexualized woman.]

Thais is what my art does; my approach is freewheeling, sexy! “Good” girls aren’t my thing; Thais is why my art does. Hence, if my poetry answers the call of its friskier subject matter, case closed—for my Muse clearly was falsely accused.

Bite me, you envious haters, Ovid’s already found stardom! I’ll be a superstar, too—if I keep doing my thing. Oh, and you’re getting ahead of yourselves. If I live, you’ll regret it more: I have lots of poems knocking around in my head. See, I like getting famous—and am, like I’m getting respected. My time is now; this ride’s raring to take off and go. Elegy artists owe me as much—they admit it themselves—as lordly epic owes Virgil for all its success.

Basta! We’ve answered the haters enough. Now pull it together, artist, and rein yourself in. Time to get back on the track.

Do you see what he’s done? Drawing on all the rhetorical training he’d mastered in law school, Ovid mounts a technical defense that appeals to “propriety of genre.” He insists that every artistic genre requires certain kinds of content, and his own chosen genre of elegy requires “frisky” subject matter; so what else can he realistically do?

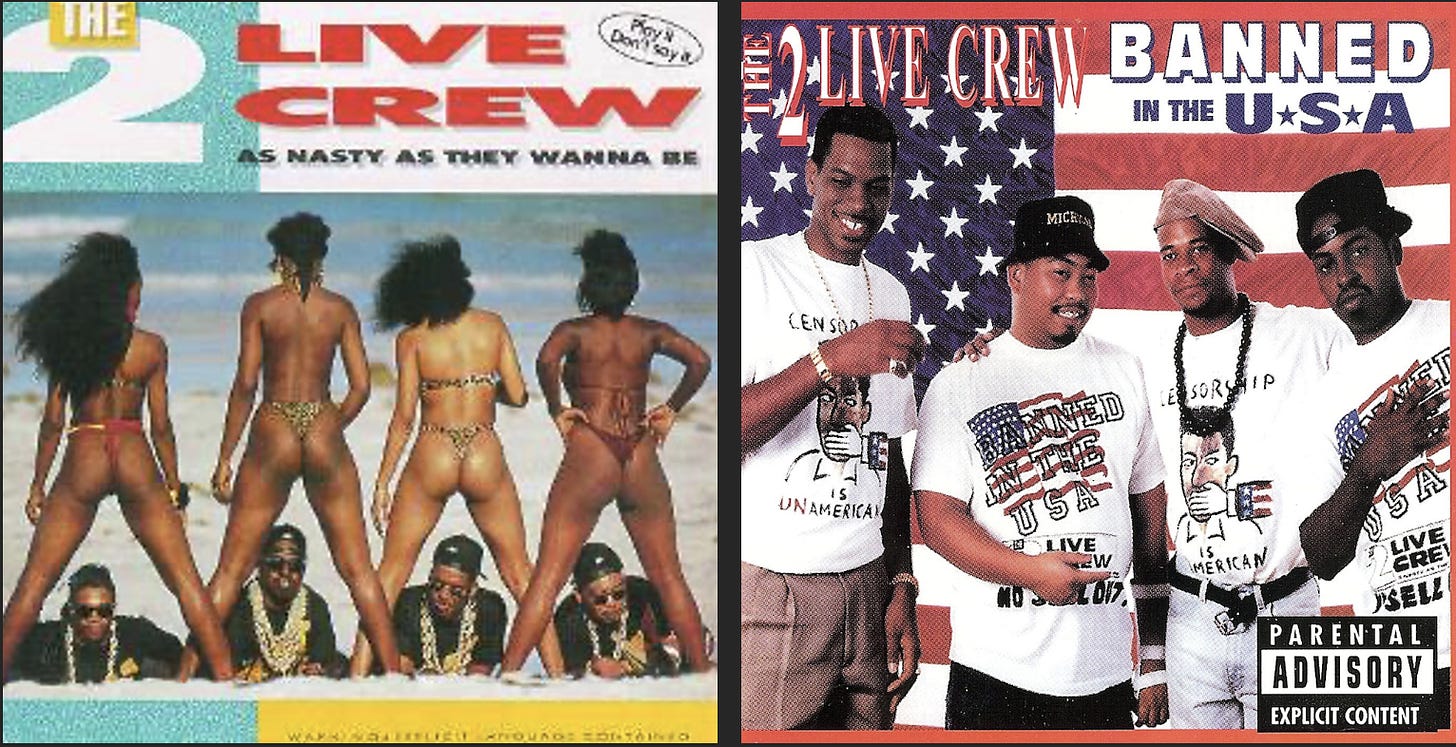

Allegations of “obscenity” are a perennial problem for edgy artists. In the American context they go hand-in-hand with hip hop.

So if Ovid’s braggadocio and vow to double down on his art and “keep doin’ my thing” reminds you of hip hop artists today, then perhaps you’ll start to see why the government got eager to censor him. Because if you remember the case against 2 Live Crew in Florida, you’ll realize there ain’t nothing new under the sun.

The translation above comes from Michael Fontaine’s new translation of Ovid’s Remedies for Love, titled How to Get Over a Breakup: An Ancient Guide to Moving On.

Bravo - nothing sacred, nothing profane.

A fascinating article that situates Ovid in a tradition of artists who have been misunderstood or maligned. We see this echoed in modern literature as well, where transgressive writers from Ginsberg to Joyce (for risque content, try his letters to Nora Barnacle!!!) position their work as part of an ongoing dialogue about what art can, and should, address. These writers all raise the question of whether art should conform to societal expectations or challenge them. In this way, Ovid’s exile becomes not just a personal tragedy, but a metaphor for the tension between artistic freedom and cultural norms—one that has been played out time and again in literary history