Dear Classical Wisdom Reader,

Well, that was fun!

If you missed it, yesterday I took part in our latest Roundtable Discussion, where I talked about the influence of the Classics on the Irish novelist James Joyce. The recording will be available for Members very soon!

We had a great time talking about the different ways the Classics come down to us, and the ‘Great Conversation’ we have with the past.

One of the ways we talked about this is through the ancient storytelling convention of the katabasis, or journey to the underworld. It was used by Homer and Joyce, but you’ll also find it in films like Moana and Frozen!

So today we’re having a look at how Homer uses this convention in the Odyssey, as Odysseus journeys in to the underworld… or at least, that’s what he’s telling the Phaeacians. Is the famously wily Odysseus telling the whole truth here? How ‘real’ is this most fantastical part of the Odyssey?

And if it’s not, what are we to make of it?

Find out below… Just don’t journey too far below!

All the best,

Sean Kelly

Managing Editor

Classical Wisdom

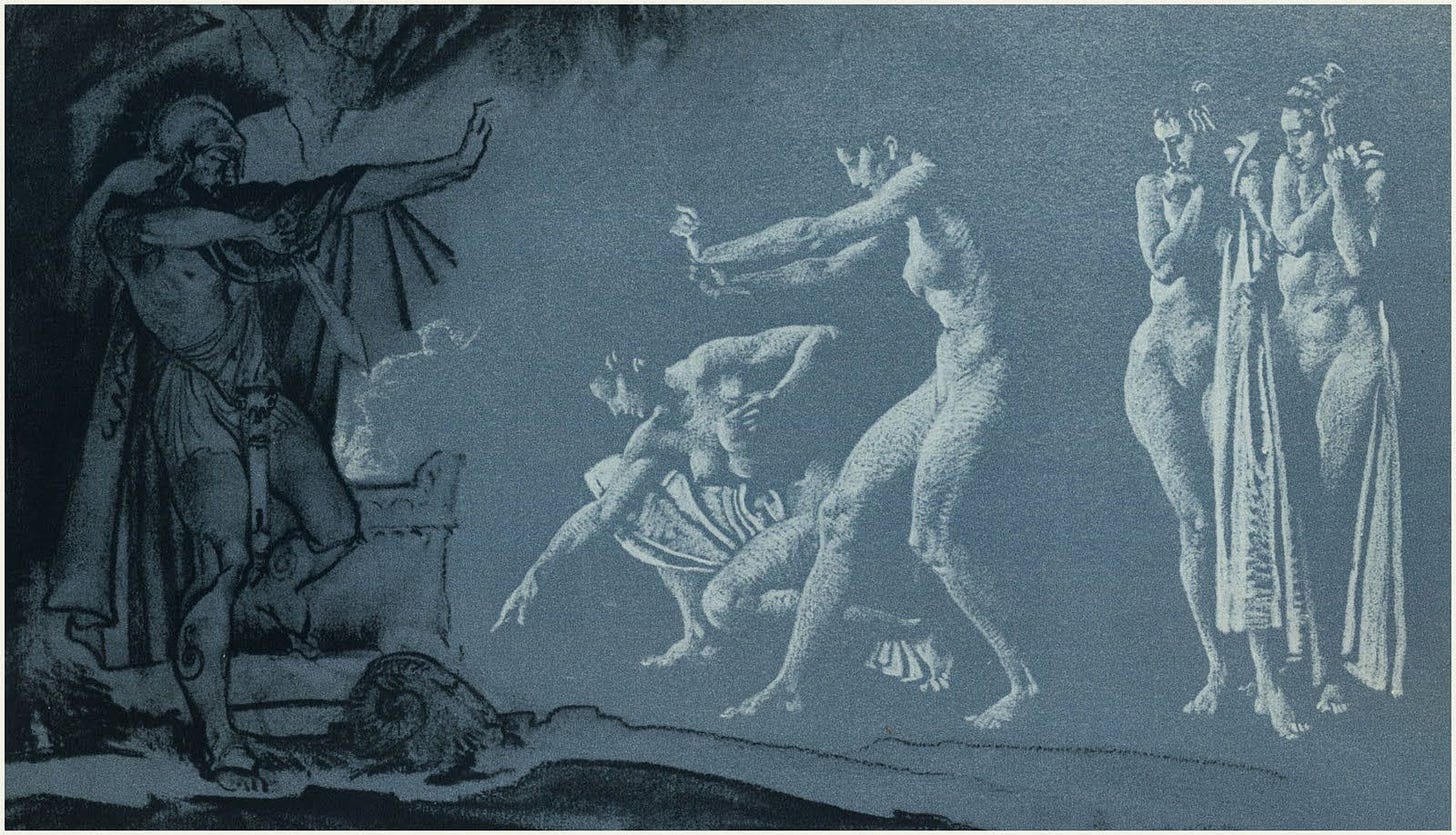

Odysseus in the Underworld

by Justin D. Lyons

The most well-known episodes in Homer’s Odyssey are the adventures described in Books 9-12. Full of one-eyed giants, amorous goddesses and narrow escapes, they are considered the most memorable and thus most likely to be included in collections of excerpts. They have received so much attention that it is often forgotten that they make up only a small part of the epic—an epic that is far more concerned with the homecoming of Odysseus than with his wanderings.

These stories are told in the first person by Odysseus himself. Given what we know of his character from both the Iliad and the Odyssey, Odysseus does not hesitate to deceive when circumstances allow. Thus, we should carefully consider the veracity of his tales. After all, Homer calls Odysseus a “man of twists and turns,” and we expect him to live up to the description.

Odysseus’ reputation thus begs the question: Is it possible that the tales are not meant to be taken as relating “real” events? In other words, could it be that Odysseus did not actually have these adventures, or at least did not have them as he relates them?

The stories Odysseus tells have a fairy-tale, magical quality about them that is different from the rest of the Odyssey. The unreal, dream-like world of monsters and enchantresses is distinct from the more realistic, historical world of Ithaca and the Greek mainland. Further, Odysseus’ stories interrupt the forward-moving time scheme of the poem; they have the character of flashbacks, contributing to the feeling of “unreality.”

It should be noted that Odysseus is speaking to an audience, the Phaeacians, from whom he is in desperate need of aid. Certainly, Odysseus is not above using his stories to sway them according to his desire.

Indeed, Odysseus may have been catering to King Alcinous, who expressly asks to hear of his guest’s exciting travels:

But come, my friend, tell us your own story now, and tell it truly. Where have your rovings forced you? What lands of men have you seen, what sturdy towns, what men themselves? Who were wild, savage, lawless? Who were friendly to strangers, god-fearing men? Tell me, why do you weep and grieve so sorely when you hear the fate of the Argives, hear the fall of Troy? That is the god’s work, spinning threads of death through the lives of mortal men, and all to make a song for those to come… (Odyssey, VIII.640-650)

Odysseus’ tales conveniently sound these same themes: the savage, the hospitable, the pious, the lawless, and death. Odysseus is on next after the great bard, Demodocus, has regaled the assembly with his songs, one of which was suggested by Odysseus himself and glorified his exploits at Troy.

Odysseus has a big act to follow and, as he is about to announce his identity as the Odysseus about whom the Phaeacians have just heard so much, it would obviously not do to disappoint. Homer here refer to Odysseus as “the great teller of tales.”

Both the reader and the Phaeacians are expecting something big, and Odysseus delivers. The Phaeacians respond well to the stories, hanging on Odysseus’ every word and showering him with even more gifts. Would not someone of Odysseus’ resourcefulness be expected to know how they would respond and be able to tailor his adventures to the tastes of his audience?

The Phaeacians appear to be a relatively innocent people. They are no match for devious Odysseus. King Alcinous goes so far as to praise Odysseus for his honesty:

‘Ah Odysseus,’ Alcinous replied, ‘one look at you and we know that you are no one who would cheat us—no fraud, such as the dark soil breeds and spreads across the face of the earth these days. Crowds of vagabonds frame their lies so tightly that none can test them. But you, what grace you give your words, and what good sense within!’ (Odyssey,XI. 410-415)

The King’s words must come off as ironic to any reader or listener aware that wiliness is the epitome of the Odyssean character. Homer, being well-acquainted with the Odyssean character, already knows what we will think about Alcinous’ remark.

Later in the poem, when Odysseus reached Ithaca, it is amply demonstrated that he is a consummate liar. Upon arriving, he spins a series of bold-faced deceptions, commonly referred to as the “Cretan lies.”

At first, he tries to deceive a shepherd boy, who turns out to be Athena in disguise.

She, of course, sees through him:

“Any man—any god who met you–would have to be some champion lying cheat to get past you for all-round craft and guile! You terrible man, foxy, ingenious, never tired of twists and tricks—so not even here, on native soil, would you give up those wily tales that warm the cockles of your heart!”

What better candidate could there be for these “wily tales” than the stories Odysseus so recently told to the Phaeacians?

Homer has left us many textual clues which suggest that the stories Odysseus tells the Phaeacians are not meant to be taken as having “really” happened. Such a view of these stories should encourage us always to be careful readers. We may encounter unexpected “twists and turns” that reveal more and deeper levels of art and meaning, inspiring us to read old books with fresh eyes.

Just as the adventures described in Books 9-12 of the Odyssey are often the most-remembered episodes due to their fantastic character, so Odysseus’ account of the underworld is one of his most striking. But did it “really” happen? Are we meant to believe that, within the horizon of the poem, Odysseus actually travelled to the underworld—or is he telling another tall tale?

Of all the stories Odysseus tells the Phaeacians, his account of the underworld is the only one to contain an interruption, emphasizing that this is a story being told to an audience. Odysseus pauses to suggest that it may be time to break off story-telling and go to sleep. But King Alcinous urges him to continue:

“The night’s still young, I’d say the night is endless. For us in the palace now, it’s hardly time for sleep. Keep telling us your adventures—they are wonderful.”

Odysseus is spinning a yarn to please a king from whom he has much to gain, and the King wants more.

Alcinous prompts Odysseus by asking if he saw any heroes in Hades:

“But come now, tell me truly: your godlike comrades—did you see any heroes down in the House of Death, any who sailed with you and met their doom at Troy?”

His host and benefactor has indicated a subject he would like to hear about, and Odysseus obliges in style, dropping a great many well-known names to help set the stage.

But if this is theater—if Odysseus is not relating something that “really” happened—what are we to make of this tale?

The story of the underworld can be seen as an expression of the hopes, fears, and doubts of a man who has been away from home for a very long time. These feelings are the material around which Odysseus builds his story. The driving themes are laid out when he questions his mother in the underworld:

‘But tell me about yourself and spare me nothing. What form of death overcame you, what laid you low, some long slow illness? Or did Artemis showering arrows come with her painless shafts and bring you down? Tell me of father, tell of the son I left behind: do my royal rights still lie in their safekeeping? Or does some stranger hold the throne by now because men think that I’ll come home no more? Please, tell me about my wife, her turn of mind, her thoughts…still standing fast beside our son, still guarding our great estates, secure as ever now? Or has she wed some other countryman at last, the finest prince among them?’ (Odyssey XI.193-205)

Anyone in Odysseus’ shoes would wonder if their aged parents were still living. The other concerns, also very natural, are reflected not only in these questions, but also in his conversations with the other shades. These concerns can be characterized as follows:

1) The faithfulness of his wife

2) The fortunes of his son

3) The honor of his house.

In the underworld, Odysseus is first confronted with a great crowd of wives and daughters of princes, whom he interviews one by one, reflecting his anxiety for the purity and success of the household. These women represent the theme of womanhood—some are faithful, some treacherous (unfaithfulness to the marriage bed receives much attention).

His conversations with dead heroes reflect the same anxiety. Agamemnon tells the awful story of how he and his men were slaughtered through the machinations of a treacherous wife and the lover she took in his absence.

But Odysseus reassures himself about Penelope’s character using Agamemnon’s voice:

“Not that you, Odysseus will be murdered by your wife. She’s much too steady, her feelings run too deep, Icarius’ daughter Penelope, that wise woman.”

Yet doubt still remains, as is evident the circumspect way he deals with her upon his homecoming.

Agamemnon also enquires about his son, Orestes. Odysseus must be wondering what kind of man his own son Telemachus has become, and how he is faring. Odysseus’ words about Orestes could just as truly be spoken of his own son:

“I know nothing, whether he’s dead or alive.”

Achilles also asks after the fortunes of his son. In Odysseus’s response we may see his hopes for Telemachus—that he will take his place among great men, proficient in feats of war and good counsel.

Achilles brings up another concern likely to resonate with Odysseus: the honor of his father and house without him there to defend them. Odysseus has already asked his mother about such things, and in Achilles’ comments we catch a glimpse of the thoughts of a son who returned to find his father abused and the honor of his house diminished:

“Oh to arrive at father’s house—the man I was, for one brief day—I’d make my fury and my hands, invincible hands, a thing of terror to all those men who abuse the king with force and wrest away his honor!”

The story of Odysseus’ journey to the underworld underlines our common humanity and the ever-lasting value of classical works. Thousands of years after its composition, readers can still identify with the hopes and fears of the hero of the Odyssey.

I see Odysseus as any one of us who strives to understand our lives more thoroughly, as when having a conversation w/ a counselor or therapist where Gestalt techniques might be used to explore the depths & meaning in the Underworld of our own identity. Aesop’s fables don’t have to be true in order to learn from them, do they?

Thank you