Beyond the Spectacle

The World of Roman Theater

Dear Classical Wisdom Reader,

It's a behind-the-scenes drama… quite literally.

I think most people have an awareness of “Greek tragedies” even if they've never read them. The plays themselves are rightly acclaimed as masterpieces, and the term has entered the common lexicon.

Yet the world of Roman theater doesn't always get its due…

In Greek drama, violent acts happen off-stage (or ‘ob scene’ in ancient Greek, hence the modern word ‘obscene’). When it comes to the Romans, though, the spectacle was one of the main draws.

A lot of the plays drawn from the same myths as Greek tragedies, retold with a bloody Roman twist.

But was it all just for show… or was there more to it than that?

Read on to discover the misunderstood world of Roman tragedy, including the plays of Seneca, the famed Stoic philosopher and statesman. Plus, how a Latin translation of the Odyssey transformed Roman theater…

And, well, if you’re interested in Homer, we have a very special treat for you.

Our next webinar will feature a rare live interview with Emily Wilson, the award-winning translator of the Odyssey and the Iliad.

Be sure to register to join us LIVE on Friday, January 23rd at 3pm EST.

Can’t join us live? Register in advance to receive the recording.

Don't miss out!

All the best,

Sean Kelly

Managing Editor

Classical Wisdom

The World of Roman Theater

by Lydia Serrant

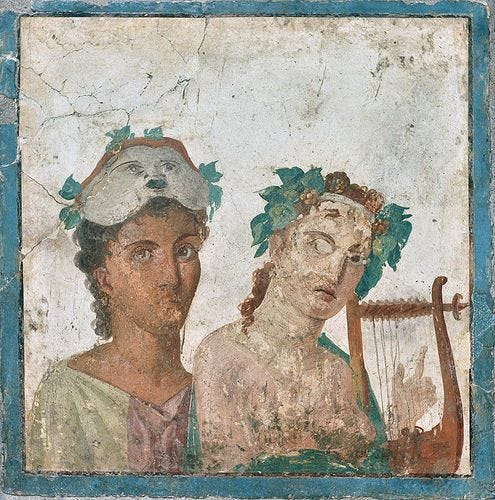

Roman theater took a while to take hold, but once it did, it spread across the Empire. The Romans adopted many of the Greek gods, so the mythological plays of Attica were a natural choice for the Roman theater. The Romans, however, had a bloodthirst that was unrivalled by the Greeks, and overall they preferred a violent comedy to the slower and more philosophical tragedies.

That was not to say that Roman theater was void of popular tragedies. The earliest surviving tragedies by Ennius (239 – 169 BC) and Pacuvius (220 – 130BC) were widely circulated and therefore, preserved for later audiences.

It was the Greco-Roman poet and former slave Lucius Accius (284 – 205 BC) that popularised theatrical Tragedy and introduced Greek Tragedy for Roman audiences. The Romans liked the adaptations so much that they used Lucius’ translations of Homer’s Odyssey as an educational book for over 200 years.

Infrastructure

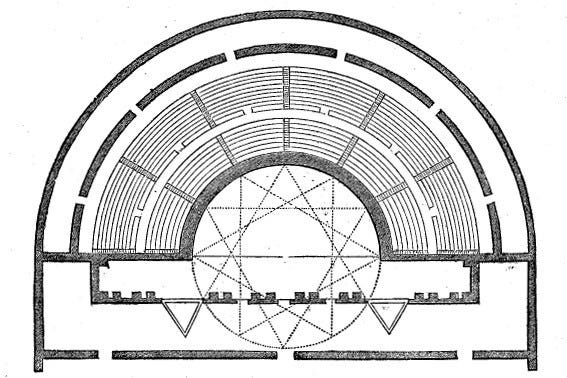

The physical structure of the theaters is the first tell-tale sign of how the Greek plays were adapted for a Roman audience.

Greek theaters were traditionally carved out of hillsides, whereas Roman theaters were built brick by brick from the ground up.

This was not because the Greeks were incapable of building magnificent theaters; history has left us with some astounding examples of ancient Greek architecture. The Greeks preferred hillsides because they did not use backdrops or props. Hillsides overlooked the city, and most of the Greek plays were set in Athens.

Of course, the Romans were not in Athens and therefore incorporated the use of backdrops and stage props to propel audiences back to ancient Greece. This also allowed to make the play more of a spectacle (in fact, the word spectacle derives, from the Latin Spectaclum meaning Public Show).

Roman Plays

The Romans copied much of the Greek when it came to storytelling and performance. There were some differences. but the basic concepts remained the same, and many of the Greek plays were translated for Roman audiences.

When the Latin translation of Homer’s Odyssey first hit the Roman theater scene, it was quickly followed by Achilles, Ajax, the Trojan Horse, and later popular comedies such as Virgo and Gladiolus.

The Romans were not without original imagination when it came to playwriting, but most of the early plays were modelled after 5th-century Greek tragedies. Later comedies favor the newer style of comedy popularised under Alexander the Great that focused not on the epic tales of the gods, but on the deeds of everyday citizens.

Become a Member and go deeper into the rich worlds of ancient Greek and Roman myth, history, literature, and philosophy.

Gain access to our archives of exclusive Members-Only podcasts, in-depth articles, e-books and more!

Whilst the majority of Roman tragedies are lost to us now, there is a significant outlier…

The Seneca Plays

Seneca was a known statesman and Stoic, and a great admirer and scholar of Greek philosophy. So how much Greek culture did Seneca consciously or unconsciously absorb into his plays?

Only eight of Seneca’s plays have survived to this day: Furens, Hercules, Medea, Phaedra, Troades, Oedipus, Thyestes, and Agamemnon. Hercules Oetaeus and Octavia are regularly accredited to Seneca, but are likely not his original work.

While it is probable that Seneca’s plays were performed within his lifetime, historians are not certain of this. What is certain is that the plays had a profound impact on theatrical history. Seneca exclusively wrote tragedies based on Greek myths.

The Romans got from Seneca’s plays what they could not get anywhere else: the opportunity to be both entertained and to learn from the philosophical master.

Seneca’s plays struck a chord with the masses and are still enacted to this day. They remained popular across medieval Europe and throughout the Classical renaissance.

His plays differ from the original Attica (Greek Athenian) plays in that they follow a five-act form instead of the traditional three, and they incorporated rhetoric structures that argued for a particular point of view or philosophical stance.

Seneca entrenched his plays in turmoil and personal conflict, and he focused on social and political issues that were relevant at the time and remain relevant to modern audiences. Known as fabulae crepidatae (Latin Tragedy with Greek subjects) Seneca’s characters were the mythological Greek characters of old, but each story was presented as a reflection of the audience’s mental state and condition of the soul.

Unlike the Attica plays, Seneca’s stage rarely gave way to the gods. Instead, inspired by the plays of Euripides and Sophocles, Seneca’s plays were bound with witches and spirits, and all manner of mystical and esoteric symbolism that resonated with his audience.

Seneca wrote his works primarily to be spoken, not enacted. However, later Roman taste preferred colorful plays to long-drawn-out auditory pieces, so actors were introduced, along with costumes, props, and choruses.

As time passed and the Roman theaters grew larger and more grand, the spoken word became increasingly more difficult to hear, so the plays eventually incorporated the choir and orchestra to guide the audience’s feelings and emotions, rather than solely relying on Seneca’s rhetoric alone.

Seneca’s plays were written to affect the human psyche, and explore the moral and philosophical territory.

Like Shakespeare, Seneca did not write for a specific place or time. Yet through dialogues and soliloquies, his plays have be re-enacted again and again throughout history, which is a testament to their popularity and longevity.

Fascinating look at how Romans transformed Greek theater into something uniquely their own. The Seneca plays are realy interesting cause they bridge entertainment and philosophy in a way that most modern theater doesnt even attempt anymore. I never realized how much the physical structure changes affected the actual content, like how Romans needed backdrops cause they weren't in Athens. That five-act structure shift probably influenced Shakespeare's approach too given how much he borrowed from Seneca's style.

I am elated to see a piece on such an overlooked topic! The didactic orientation of Roman drama, along with its spectacle-centric elements, reflects the high value Roman culture placed on rhetoric, action, and public display. Roman theatre offers a fascinating counterpoint to Greek tragic theatre, where mythopoetic demonstration and the audience’s cathartic experience were central.