Dear Classical Wisdom Reader,

It quickly became a spirited debate… after all, there is a lot on the line and it’s certainly not a point to be conceded without a fight.

We were discussing the concept of free will… and whether we have it… or not.

My interlocutor was steadfast and impassioned.

No, he said. None at all. Zero free will.

He was quick to quote others.

Writes Stephen Cave in the Atlantic:

“The sciences have grown steadily bolder in their claim that all human behavior can be explained through the clockwork laws of cause and effect.”

“The challenge posed by neuroscience is more radical: It describes the brain as a physical system like any other, and suggests that we no more will it to operate in a particular way than we will our heart to beat.”

“Brain scanners have enabled us to peer inside a living person’s skull, revealing intricate networks of neurons and allowing scientists to reach broad agreement that these networks are shaped by both genes and environment. But there is also agreement in the scientific community that the firing of neurons determines not just some or most but all of our thoughts, hopes, memories, and dreams.”

It is this understanding of neuroscience that has led many to relinquish their fundamental belief in the control of our own choices.

But where does insisting on a diminished Free Will leave us? How does it affect our moral codes, criminal justice systems, religion, and indeed, our very understanding of life itself?

If every moment in life is simply the result of predictable outcomes of mechanical laws, what’s the point of it all?

Of course this debate has been raging since the birth of philosophy. Early myth-makers were, in their fear of the gods, more than ready to submit themselves to the Moirai (the Fates), who were thought to determine every person’s destiny at birth.

The Pre-Socratics (or as I like to term them, the First Philosophers) wrestled control from the gods to nature. Thinkers like Anaximander and Heraclitus believed in the logos behind nature, while the materialist philosophers Democritus and his mentor Leucippus claimed that all things, including humans, were made of atoms in a void, with individual atomic motions strictly controlled by causal laws.

Socrates famously claimed ignorance was the cause of evil (since no man does wrong willingly) rather than individual agency whereas Aristotle, in his Physics and Metaphysics, said there were “accidents” caused by “chance (τυχή)”, though this is a gross simplification of Aristotle’s more nuisance exploration into the inquiry.

Nonetheless, so far it appears Free-Will isn’t storming ahead.

Then Epicurus and the Stoics came into the scene and formulated clear nondeterministic and deterministic positions.

One generation after Aristotle, Epicurus built on the Macedonian’s understanding of why things happen by adding a few other causes:

“…some things happen of necessity (ἀνάγκη), others by chance (τύχη), others through our own agency (παρ’ ἡμᾶς).”

…necessity destroys responsibility and chance is inconstant; whereas our own actions are autonomous, and it is to them that praise and blame naturally attach.”

It wasn’t until the Peripatetic philosopher Alexander of Aphrodisias (c. 150–210) defended a view of moral responsibility, that we find something that we would call libertarianism today. While Greek philosophy had no precise term for “free will” as did Latin (liberum arbitrium or libera voluntas), Alexander termed the discussion in regards to responsibility, what “depends on us” (in Greek ἐφ ἡμῖν).

Man is responsible for self-caused decisions, Alexander argued, and can choose to do or not to do something, adding to the Stoic philosopher Chrysippus.

So where does this leave us, dear reader? Sorting through the wisdom of the past and the science of today, we have to take a step back while looking deep inside our own thoughts and decisions and ask:

Do we have free-will? And if we don’t… Or if we do… What are the many consequences?

You can reply to this email, write to me directly at anya@classicalwisdom.com, or comment below.

As for today’s mailbag responses to the question: Would you kill the fat man (an ethical philosophical question known as the Trolley problem), we had a comment on Substack notes that it was an example of the over-complication of philosophy. I was quick to reply that actually, of the many difficult and sometimes abstract philosophical questions that exist in the world (and trust me, there are plenty!), this was actually one which has direct real world practical application: specifically regarding self-driving cars.

There are algorithms that are being programmed as we speak to make these ethical choices. Should a car swerve to miss a crowd, killing the inhabitants inside? What if there was only one person it was saving, but four people in the car? What if one of them was pregnant? Or a convict?

As you can see, the question becomes infinitely complicated… and so perhaps it’s not surprise that the replies to last week’s inquiry are extremely diverse. The musings from your fellow Classics loving readers reveal the intricate difficulties of this philosophical exercise.

Read on below and see who you agree with, with whom you disagree and if there can be any solution at all....

All the best,

Anya Leonard

Founder and Director

Classical Wisdom

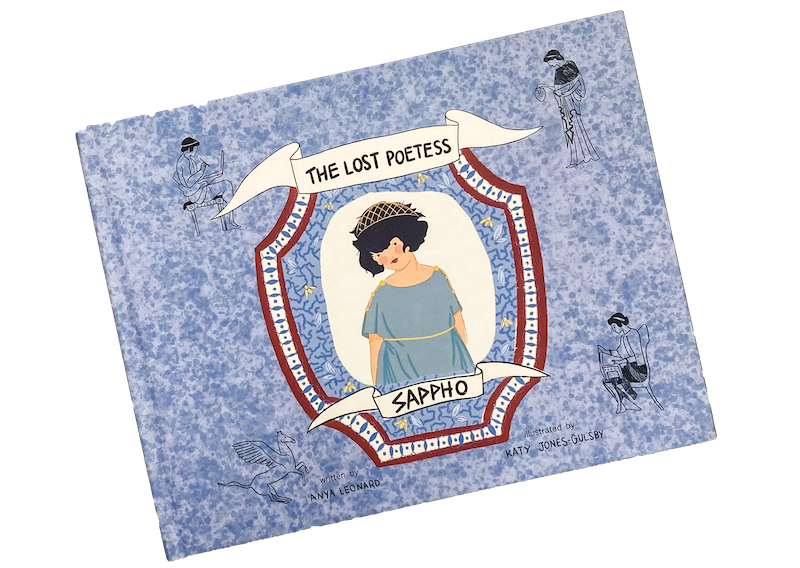

P.S. Our Essential Classics limited edition books are officially sold out! If you missed out on our anthology, there is still time to get our Lost Poetess Children’s book as well as our other Classics inspired products, like our Essential Greeks puzzle or our Classical Wisdom notebook.

You can see everything at our shop... but make sure to check it out while they are still in stock!

Monday Mailbag

Re: Would you kill the fat man?

Hello Anya,

I would neither pull the lever nor push the fat man. A life’s value cannot be reduced to numbers, and to measure it in this way is deeply inhumane. Assigning a numerical worth to someone’s existence leads to conclusions that are inherently unethical and ultimately supports a utilitarian mindset—a philosophy I cannot stand by.

However, if I were absolutely certain that the fat man was the one who tied the five people, then yes, I would push him. In such a scenario, his actions directly endangered others, and stopping him would feel justified.

Best regards,

Razeen A.

-

The solution, I suggest, is in setting the switch in its halfway position, effectively derailing the trolley and saving all six lives.

Very much enjoy reading your missives and studying classical thought!

Stephen

Hello Anya,

The premise is that this is an ethical problem, but the reader is asked to choose between utilitarian choices.

It is unethical to choose who should die in place of whom.

You can only choose to put yourself at risk (by whatever means are available).

David B.

-

Easy.

I wouldn't push the fat man, at least in Judith's version.

Instead, I would apply my best skills of persuasion, as quickly as I could, and present the dilemma to the Fat Man himself.

That way, he could choose whether he wanted to jump for the greater good... or let the others die instead.

After all, isn't that choice really up to him and not me?

P.S. I think that toddler is going to grow up to be President one day -- and not in a good way.

P.P.S. Your variation on the fat man example, where he's evil...

That tells us a little something about the fat man, but not much, and doesn't tell us anything about the five people. Maybe the fat guy is a Nazi and the other five are also Nazis. And he's killing them because he's courting the fuehrer's favor and attention. In that case, the toddler has it right?

Ah, but, in what way is the fat man evil? Is it because he cheats on his taxes? On his wife? On his diet?

If that smacks of moral relativism, what about the broad and universal principles of justice, civility, and fairness. In a society ruled by law, doesn't even this plump vermin -- whom I seem to be hanging out with for no good reason, so shame on me -- deserve due process before conviction?

Maybe we should forget them all, take pictures of the aftermath, and sue the trolley maker for billions... so we can distribute same-said windfall to the poor and sick, thereby saving the lives of thousands. Or to a biotech firm doing key medical research, thereby saving the lives of millions.

Seems like it's worth a fat guy and five of his buddies, no?

John F.

This question has always reminded me of the math exam questions in which the correct answer is, "Not enough information."

Do any of them have dependents? Are they prone to commit murder? If the fat man tied them up, is it because they've all done something terrible?

Given the time pressure, you could take the Darwinian stance that they let themselves be abducted and tied to the tracks. Isn't there something to be said for keeping oneself out of this situation?

And a question that isn't asked often enough is: Are the people on the tracks screaming in terror, or are they calm and composed? Perhaps they're dying for something they believe in. Should I rob them of martyrdom?

Maybe the toddler has it right, and it's best to assume guilt from all available parties and put the fat man at the end of the line if you can.

Daniel D

-

Kill the fat man. Five people saved instead of one evil one.

Sandra

Hi Anya,

I am writing to you regarding the Trolley Problem. At face value, this thought experiment seems to lead one to a utilitarian solution. Who wouldn't want to save five people by sacrificing one, right? And yet, when we look at the history of humanity, I believe we ought to consider the adage, "the road to hell is paved with good intentions." Many times we make sweeping decisions that have unforeseen consequences. Most of the time, we make these decisions because we think we are doing good.

The Trolley Problem is an ethical thought experiment, but for those who are religious or spiritual, it also entails a choice affecting one's own karma, or action. The fact that the train is headed for one person is fate. Once you make the decision to throw the switch, you have now taken action to murder a person based on your own perception of what is good. You have now altered what is known in the legal industry to this day as "an act of God" by consciously causing another person's death, when previously you were merely an observer of the action of fate. You are now responsible for a person's death, when you previously were not. That is not something which should be taken lightly.

Now, let's say you throw the switch incorrectly, so that it only partially moves. This causes the train to derail and explode, killing the 300 people onboard, as well as the five people tied on one side of the track and the one person tied on the other track. Perhaps it even kills you too. Perhaps the scientist who had just discovered the cure to cancer was on the train with the proof of his cure. Now you are directly responsible for many deaths. In the case of the one fat man standing in the way, you posit that the man is evil. Well, that would make the decision somewhat easier.

But, let's say you don't know anything about him. He could be the one person supporting his village, the one bread winner paying to support orphans and widows. He could be the scientist about to cure cancer. The only truly ethical solution in the Trolley Problem is to allow fate - the will of the gods, or the will of God, or simply the workings of nature - to play out. Too often we humans believe we have the best solution to change the world and it ends up that we make it worse.

Sincerely,

Chase H.

-

A fat man doesn't weigh much more than you do... YOU jump!

Outrageous.

Better question, would you sacrifice yourself for the five?

Alice.

My Solution to the Free Will conundrum.

The brain's operation is vastly subconscious - we cannot possibly be aware of (have thru our conscious window) all that is going on inside of it.

The subconscious input is a constantly, randomly changing, dreamlike state of imaginings mostly related to the possibilities within our current environment and our past experiences (including even our past imaginings). Its nature is truly random in the sense that even quantum fluctuations affect it, which means that not all the imaginings will be determined totally by our current environment and our past experiences.

The subconscious must have some method of choosing the very few imaginings which occur there which it decides to present to the conscious mind (occasionally even in an eureka! moment). In this manner, the subconscious can present to the consciousness choices of imaginings (decisions) which are not fully determined by our current inputs to our mind, even though they are most definitely related to and constrained by those current inputs. The conscious mind is but a small window on the subconscious mind positioned by the subconscious.

I thought of this solution over 20 years ago and have happily held it ever since. All my life I have trained my subconscious to present to me only imaginings that will be in my most rational (widest and farthest sensing) self-interest, not always successfully, but that has been my goal, hopefully I get better all the time.

Whether or not you think you have free will, you’re correct.