Let's Talk About Heroes (maybe)

The heroes of antiquity were a force to be reckoned with. They could best any man in battle, win against odds that seemed impossible, outsmart everyone but the gods…and…throw temper tantrums, watch hundreds of men die because of their stubbornness, treat women unfaithfully, unfairly, and downright murderously, murder their children, and uproot (or kill) whole cities for the most unsavory reasons.

It’s not a side to the ancient heroes that we often talk about, but it’s a side that definitely exists and really can’t be ignored.

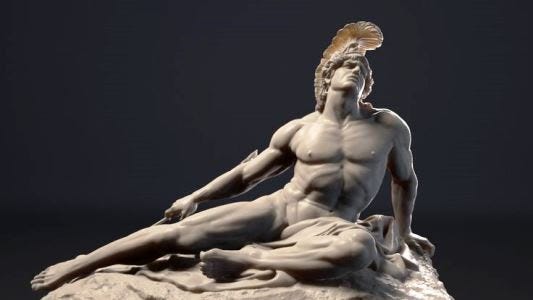

Heroic Warrior…or…Cry-baby?

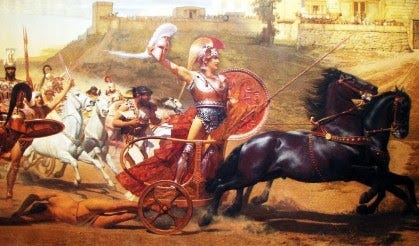

Achilles drags Hector’s lifeless body behind his chariot

Achilles is probably the most famous example of an applauded ancient hero who, to our modern sensibilities, can seem like a child throwing a temper tantrum. Achilles was well known for his strength, his prowess on the battlefield, and his apparent invincibility. He was an obvious pick to lead a battalion of troops in the Trojan War, and for a while, he really turned the tide of the war in favor of the Greeks—that is, until he didn’t get his way.

According to Homer’s Iliad, Achilles flatly refused to fight after his battle prize, a young woman named Briseis, was taken from his by Agamemnon, the commander of the Greek forces. Even after hundreds of men died, and even after Agamemnon desperately tried to return Briseis, Achilles absolutely refused to return to battle, and only did so after a beloved friend of his was killed. He says:

Neither Agamemnon nor any other Greek will change my mind, for it seems there is no gratitude for ceaseless battle with our enemies. He who fights his best and he who stays away earn the same reward, the coward and the brave man win like honour, death comes alike to the idler and to him who toils. No profit to me from my sufferings, endlessly risking my life in war. I am like the bird that brings every morsel she finds to her unfledged chicks, and goes hungry herself. –Homer (Iliad)

What matters to him is not that, as Odysseus has just told him, the Trojans are poised to decimate the Greek forces, but that he has been dishonored by not getting his just rewards.

Then, to put the cherry on top, after killing Hector, the Trojan hero, he desecrated Hector’s dead body by dragging it behind a chariot until it was torn to shreds.

So, let’s see—if keeping a woman as a “battle prize” isn’t bad enough to our modern sensibilities, what about Achilles’ pettiness, selfishness, unchecked anger, and his disregard for the respect we still believe belongs to the dead? His hero status, at least by our standards, is on shaky ground, it seems.

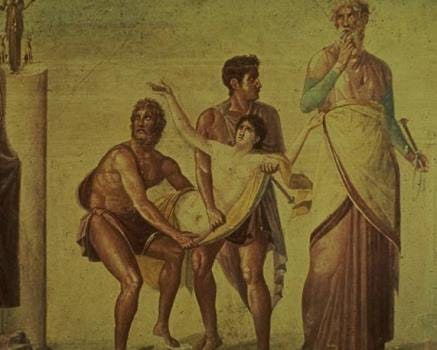

Some Questionable Behavior

And Achilles isn’t the only one. Agamemnon, the aforementioned commander of the Greek forces, willingly sacrificed his own daughter, Iphigenia, so that the Greek fleet would have favorable winds when sailing to Troy. Odysseus, our favorite trickster hero and strongman, helped Iphigenia into thinking that she was being taken to the place of the sacrifice to be married. Ajax, another famous hero of the Trojan War who was revered for his strength and courage, made it out of the war alive but killed himself in a rage when he lost a competition to win Achilles’ magical armor. And these are just a few examples of “questionable behavior” on their part.

Iphigenia about to be sacrificed

Again, these heroes—while they were obviously revered in their own time—are seeming a little lackluster by our modern heroic standards, which tend to emphasize self-sacrifice, humility, and justice. Of course, it’s impossible for us to really judge centuries-old characters by standards so far removed from their own time and societal norms; but it’s certainly interesting to see how the concept of a hero has changed over time. Based on these examples, it would seem that some ugly behavior (though it wasn’t necessarily acceptable even to ancient society) was considered overlookable in the face of glory.

Don’t Forget the Romans

It’s not all Greek heroes either. The famous Roman hero (and legendary founder of Rome), Aeneas, exhibits his fair share of “complicated” behavior. He nearly brutally kills a woman (Helen) during the Fall of Troy, and the fact that he even considers committing this heinous act (which was considered unacceptable even in ancient times) is a telling mark on his character. Famously, at the end of Virgil’s Aeneid, Aeneas brutally slaughters an opponent even after that opponent admits defeat and humbly begs that his life be spared. Again—not looking so pretty.

Aeneas ignores Turnus’s cry for mercy

In fact, there is a small but significant portion of modern opinion that has begun to see the very event for which Aeneas is considered a hero—his conquering of the city of Latium in order to found Rome upon that spot—as an act of terrorism and brutality. This opinion goes so far that it has resulted in an enormous controversy over the use of a quote from the Aeneid in the recently opened 9/11 Memorial.

The quote, though beautiful (“No day shall erase you from the memory of time”) refers to two of Aeneas’s soldiers, who sneak into an enemy camp in the middle of the night and slaughter dozens of unsuspecting men in their sleep, and are killed for it afterward. This context, argue a number of classicists, appears to make the quote in the 9/11 Memorial sympathize more with the aggressors than the victims.

"You are the victor, and the Ausonians have seen me stretch out my hands in defeat: Lavinia is your wife, don’t extend your hatred further." – (Turnus, in Virgil’s Aeneid)

Clearly, the ancient heroes were not only nuanced, but also fairly complicated characters. This leads us to some major questions that we should be asking ourselves as modern readers of these narratives: Why were these men still considered heroes despite their (often ugly) behavior? Was heroism in the ancient world nothing more than incredible strength, skill, and the ultimate achievement of kleos (glory), despite selfishness or pettiness?

Or, from a different angle: were these heroes loved and revered not in spite of, but because of their flaws? Did these flaws, these behavioral quirks, somehow make them appear more human, more like us?

I'm just relishing the feminist retellings...

The Illiad from http://rogermcooke.net/

Cooke May 10, 2021

The Trojan war is said to have ended in 1184 BC. Homer’s epic is dated between 850 and 630 BC. It is perhaps the greatest work in Western literature, so great that everyone can find in it what they want to see. Here’s what I see: Homer is an atheist and pacifist and the Illiad is a searing indictment of religion and warfare with an appeal to the frail shred of good in humanity.

The book is mostly about the gods. They are vain, supercilious, cowardly, deceitful and thoroughly despicable. They are worshipped out of fear for retribution. History is just a game board for their amusement. Men attribute everything to the gods; if they act cowardly it’s because the gods filled them with fear. If they take heart and prevail, the gods gave them that heart. Hercules killed his children because jealous Hera, to get even with Zeus for having screwed Hercules’ mother, made them appear to Hercules as monsters. Humans lack any agency. Homer mocks the gods from beginning to end. Here’s one example which I haven’t seen others pick up. Hera wants to seduce Zeus so she can help the Greeks against Zeus’ favored Trojans (Book 14). She tricks Aphrodite into loaning her magic bra, and tricks Sleep by promising him her daughter. Zeus is aroused and courts Hera by telling her that he is hornier for her than for all the other women and goddesses he has raped. “But for us twain, come, let us take our joy couched together in love; for never yet did desire for goddess or mortal woman so shed itself about me and overmaster the heart within my breast—nay, not when I was seized with love of the wife of Ixion, who bare Peirithous, the peer of the gods in counsel; nor of Danaë of the fair ankles, daughter of Acmsius, who bare Perseus, pre-eminent above all warriors; nor of the daughter of far-famed Phoenix, that bare me Minos and godlike Rhadamanthys; nor of Semele, nor of Alcmene in Thebes, and she brought forth Heracles, her son stout of heart, and Semele bare Dionysus, the joy of mortals; nor of Demeter, the fair-tressed queen; nor of glorious Leto; nay, nor yet of thine own self, as now I love thee, and sweet desire layeth hold of me.”

Zeus doesn’t know he’s being played.

The Illiad comprises just a few weeks of the 10 year war, starting with Agamemnon seizing Achilles’ salve girl prize Briseis (won by killing her parents), with whom Achilles has fallen in love and promises to marry - the very same crime for which the Greeks attacked Troy (the gods made Paris and Helen do it). Achilles pouts, the Trojans prevail under Hector until Hector kills Patroclus. Achilles then kills Hector and drags off his body to feed to the dogs. The body of Hector is a prize even greater than the fairest slave girl. Now Zeus asks Achilles to give up this prize and let Priam take the body for proper burial – for a proper ransom. Achilles accedes.

But when Priam visits Achilles, Achilles finally does something which the gods have not told him to do.

“Then spake to him in answer swift-footed, goodly Achilles:“Thus shall this also be aged Priam, even as thou wouldest have it; for I will hold back the battle for such time as thou dost bid.” When he had thus spoken he clasped the old man's right hand by the wrist, lest his heart should any wise wax fearful.”

Compassion! No god told Achilles to take Priam’s hand. Finally someone acts on his own agency, free of the gods’ manipulation. The Iliad ends with the burning of Hector’s body and burial of this bones. It’s frail hope but hope nonetheless. And the god worshippers don’t even know they’re being played.