Dear Classical Wisdom Reader,

Now, I didn’t think I was going to end up talking about mixed martial arts this week, but it really is amazing what we owe to the ancients.

Last week, we talked about the early atomists, whose thought prefigured the science of centuries later. I finally saw the Oppenheimer film since then (I thought it was astonishing), but I didn’t realize that he’d been referred to as the American Prometheus. The Classics really are everywhere.

This week, we’ve got something a little less theoretical and a little more physical.

We’re looking at the Greek fighting competition known as the pankration, a key event in the ancient Olympics. Was it really an ancient version of mixed martial arts? Find out below, alongside its mythic origins, and its vast yet overlooked legacy.

All the best,

Sean Kelly

Managing Editor

Classical Wisdom

Greece’s Forgotten Fighting Legacy

by Jakob Renner

Ancient Greece is famously known for its rich culture, especially with regards to philosophy, art and noted intellectuals, but it is their sport which we are interested in today. In particular, the often unrecognized Greek contribution to the world of martial arts, a discipline known as the pankration.

Jim Arvanitis, a renowned member of the Martial Arts Hall of Fame, states that pankration is the first type of mixed martial arts of which we know. The origins and exact age of this fighting form, however, are hard to determine.

Legend says that Hercules developed pankration in order to become more formidable in wrestling tournaments. Another origin story by Plutarch is that Theseus created the pankration in his battle with the Minotaur. While these are just myths, the fact that pankration is connected to these revered heroes shows its importance to ancient Greek culture. All the more evidenced by the fact that pankration was one of the main events of the ancient Olympic games.

But what exactly is pankration? And how was this martial art practiced?

To begin with, pankration means “all power”. It was known in ancient times for its ferocity and allowance of such tactics as knees to the head and eye gouging.

One ancient account tells of a situation in which the judges were trying to determine the winner of a match. The difficulty lay in that fact that both men had died in the arena from their injuries, making it hard to determine a victor. Eventually, the judges decided the winner was the one who didn’t have his eyes gouged out. Over time, however, maneuvers like eye gouging were discouraged to prevent such unpleasant incidents.

While pankration may seem from these stories to be little more than a brutal free for all, it did have its formal stances (Stasi), punches (Efthia), kicks (Laktismata), and blocks (Apokrousis).

The only rules that were enforced by referees, with beating sticks in hand, was no gouging (eventually) or biting. This meant that competitors could be very creative with their attacks and defense, resulting in a plethora of options. Indeed, describing every pankration movement would require writing a complete book.

In the end of the day though, the main goal in a match was to get your opponent to submit by raising an index finger in the air as a yield signal. The most common way to get this submission was a movement called a “choke”. This could be done with a front grip, where the trachea and windpipe are squeezed, or with a rear choke, where the carotid arteries are closed by a forearm from behind.

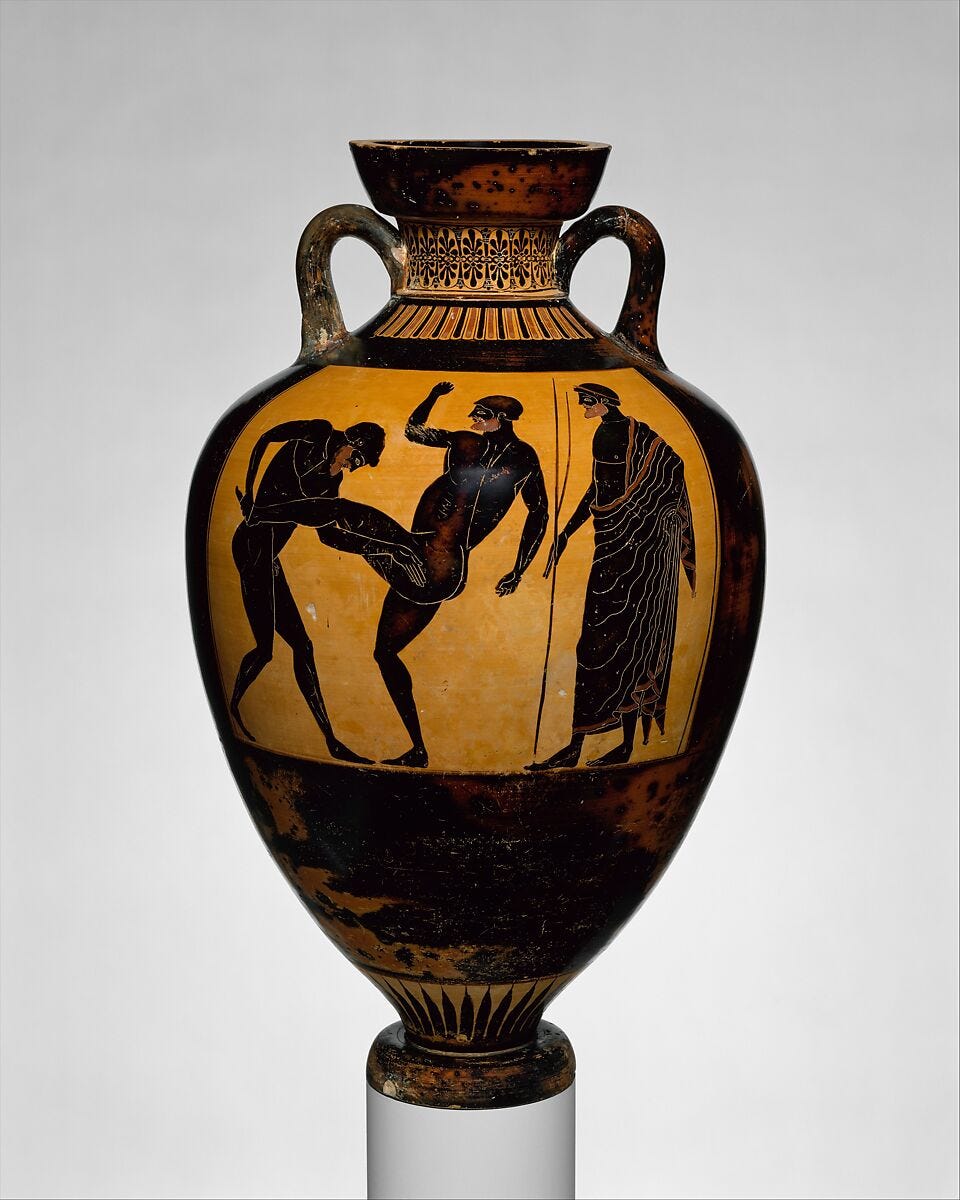

Aside from chokes, an array of kicks, punches and blocks were used. Artist depictions on pottery show kicks to the stomach and shins. Punches had the best range of options from jabs to uppercuts and hooks. While blocking involved a key principle that is still taught by martial artists today, adapting to your opponent and looking for opportunities to counter their movements.

An example of this would be when your opponent is throwing a hook punch and your elbow point is used to absorb the impact of the knuckles. Then, while your opponent’s arm is extended, you punch the bicep and forearm crease with your free limb – effectively immobilizing your opponent’s remaining arm.

This type of movement shows an interesting similarity to techniques found in Eastern martial arts, such as Kung Fu, Karate and Muay Thai.

But maybe this isn’t surprising at all… especially when you consider that Alexander the Great was a noted pankration fighter. The famously ruthless Macedonian could have brought the martial art as far as his conquests in the Indus Valley, where cultural exchange could have allowed pankration to spread to China and South East Asia.

While we we’ll never know for certain, perhaps in this way pankration may very well be the mother of all martial art forms. The ancient Greeks left a tremendous legacy that is regularly represented by their art, literature and philosophy, but it is often overlooked that they did likewise in the field of fighting as well.