Dear Classical Wisdom Reader,

We like to think we live in an age of political turmoil. I’m not sure why, perhaps it’s the excitement of it all and the sense of being part of something bigger than ourselves that we wish to be witnesses to an important and volatile moment in history.

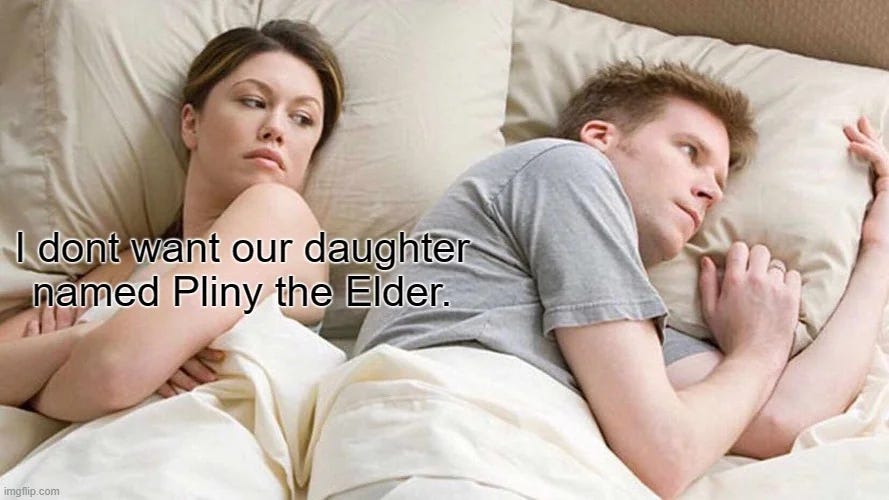

Indeed, the internet is awash with comparisons between our modern era and the end of the Roman Republic... as well as (apparently) the men who like to think about it.

But, as good philosophers, it is worth questioning if this is really the case. Are our current events marked with the same blood, sabotage, political marriages and potential poisonings that fill the history books?

For instance, is there one politician, male or female, whose life is as dramatic, complicated and complicit as Fulvia, the woman whose political debut came from a grave, who raised armies, and apparently pierced the tongue of Cicero?

Much, much more than a footnote to history, the aristocratic Roman woman was so instrumental during Rome’s most tumultuous era that she was often described as the “Fourth Triumvirs”... because she completed the powerful political alliance between Octavian, Mark Antony, and Lepidus, which ruled Rome from 43–33 BC.

But how did the chroniclers of time depict this matron, who went head to head with the future Roman Emperor, Augustus? Did they record her as instrumental or disruptive? And as the first Roman non-mythological woman to appear on Roman coins, do their descriptions match the archeological evidence?

Or were the ancient historians happy to indulge in a bit of excitement, carried away by their own moment in time?

Classical Wisdom Members can enjoy today’s article to discover the life and the legacy of Fulvia, whose actions were interwoven with the end of the Republic and the rise of the Empire. Indeed, her story is key to understanding one of history’s most important junctures...

So read on to discover this potentially parallel time and comment below whether you think our modern era is truly comparable to those fateful moments leading up to 27 BC...

All the best,

Anya Leonard

Founder and Director

Classical Wisdom

P.S. Today’s article was written by Mary Naples, author of two books, including Cult of the Captured Bride: How Women Took Power and Unsung Heroes: Women of the Ancient World.

Classical Wisdom Members can enjoy Mary’s most recent book, Unsung Heroes: Women of the Ancient World in our Member’s Ebook Library and below today’s article.

Fulvia: The “Fourth” Triumvirs

By Mary Naples

History has long been unkind to Fulvia (85/80 BCE-40 BCE)—the notoriously jilted wife whom Mark Antony abandoned for the Queen of the Nile. The ancient chroniclers portray Fulvia as a jealous and vengeful wife, claiming that she committed numerous atrocities. These include inciting a riot in the Roman Forum that destroyed the senate house, repeatedly stabbing the tongue in Cicero's decapitated head, and initiating a war with Octavian—Rome's future emperor known to posterity as Augustus—in an attempt to entice her husband back to his matrimonial bed. The ancients denounced and disparaged Fulvia in the most heinous terms simply because she dared to defy patriarchal notions of femininity.

Ancient Rome chastised women for drawing public attention to themselves or usurping male authority, considering modesty and humility as prime feminine virtues. Clearly, Fulvia was a woman who did not know her place.

More than just a footnote in the annals of ancient Roman history, most historians are quick to overlook that Fulvia had once been Rome’s most admired woman. She was the first non-mythological woman to appear on Roman coins and used her political influence to challenge the traditional gender roles expected of Roman matrons. Married to three powerful political figures, Fulvia was not content to wile away the hours with the feminine pursuits of spinning or weaving. During a time when historical narratives largely relegated women to the background, Fulvia encroached on the masculine pursuits of politics and military, leading ancient chroniclers to unfairly portray her as envious, vengeful, and troublesome, akin to the goddess Juno.

This portrayal, in fact, persists even among modern historians, who often accept the misogynist biases of the ancients as incontrovertible facts. But are these depictions fair? What was her often overlooked role in the political dynamics of the day? How did her actions not only influence her husbands’ legacies but also leave an indelible mark on the power structures of the time?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Classical Wisdom to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.