Euripides

The Greatest Writer of Greek Tragedy?

Dear Classical Wisdom Reader,

He reinvented Greek myths, and revolutionized theater.

Even now, millennia after his death, he’s still considered controversial.

And personally, he’s one of my favorite writers of the ancient world.

Today we’re looking at the life and work of Euripides, the tragic playwright behind enduring and powerful works such as Medea and The Bacchae, as well as comparatively lesser known plays like Alcestis.

He’s also one of the many ancient figures being covered in our upcoming course The Essential Greeks.

Through video lectures, live webinars, Q&As and more, we’ll be looking at some of the most important and influential thinkers and writers of ancient Greece. Alongside Euripides, we’ll be diving into the likes of Socrates, Homer, Aristotle, and more…

Our course starts on Monday, October 2nd, so there is STILL TIME to enroll.

You can do that HERE.

So don’t miss out… it would be a tragedy!

All the best,

Sean Kelly

Managing Editor

Classical Wisdom

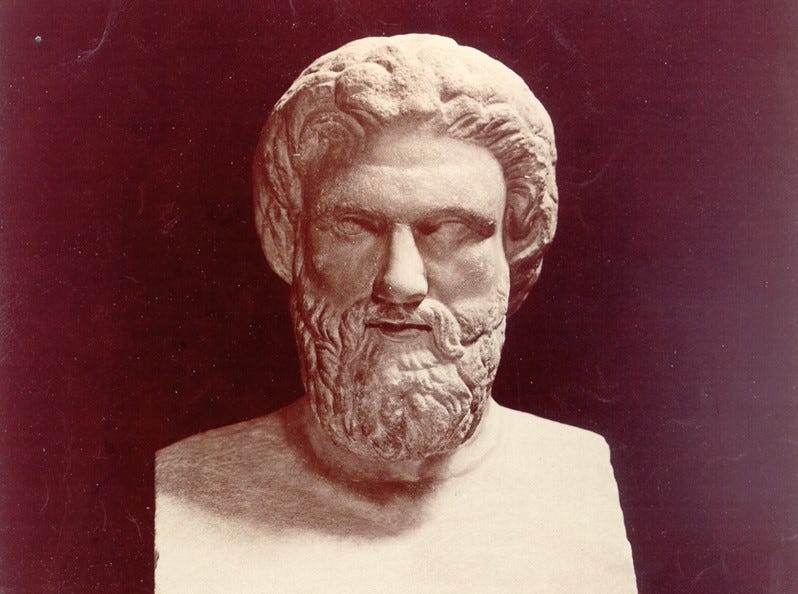

Euripides - the Greatest Writer of Greek Tragedy?

by Ben Potter

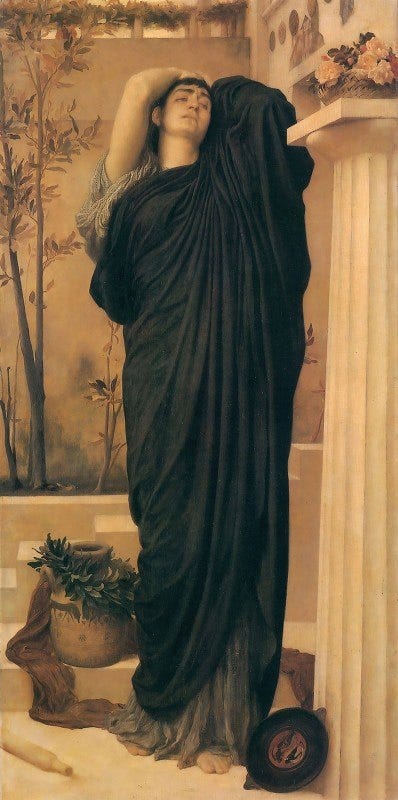

A lone figure, swaddled in rags, sits secluded in a dank cave bent over his papyrus. The whittled reed in his hand dips rhythmically into the pot of octopus ink before adding a couple of urgent scratches to the thick page. His bushy, white beard is stained off-center at the lower-lip, evidence of his habitual pen-chewing; but it is his mind, his mind that is stained far more indelibly. There are images of gods, war, warriors, adultery, incest, exile, blasphemy, damnation, infanticide, patricide, matricide, human-sacrifice, and worse. These are the ideas, the dark and evil components of Greek tragedy, that this man, this Euripides believes are too… too… stock, too trite, too bedtime-story for the citizens of Athens. He knows that beauty is terror. As Donna Tartt once wrote, “Whatever we call beautiful, we quiver before it.”

Well… No. I’m afraid not. At least, we’ve no reason to believe that the man who produced, directed and wrote The Bacchae, Hippolytus, Medea, and Electra really was the tortured recluse, the artistic oddball, the Salinger or Kubrick of his day. We like to think this because, instead of merely putting a new spin on traditional Greek myths, he always managed to find an even more shocking way to deliver a tried and trusted tale. He could make heroes devils and devils heroes and all without forcing the audience to break their mental stride.

Yes, he may well have lived in a cave on the island of Salamis, but what better place for a writer to escape the distracting hustle and bustle of Athenian city existence?

Likewise, late in life, Euripides left Athens for Macedon in self-imposed exile. Was he frustrated at a theater-going public who didn’t appreciate him? Or was it, more likely, a lucrative retirement where his talents were rewarded not only with money, but also with praise and status?

After all it was these, praise and status, that seem to have eluded Euripides during his lifetime. Despite being considered by many today as the finest of the three great Athenian playwrights (besting Aeschylus for style and Sophocles for substance), he only won the first prize at the city’s premier dramatic contest, the Great Dionysia, four times during his lifetime, and once posthumously.

You may be thinking ‘that’s not so bad – nobody ever won more than four Academy Awards for best director’, but if you compare his record to that of Aeschylus (13 wins) and Sophocles (20+), it seems a paltry return for a man of such insight, intensity and timeless genius.

Don’t think however, that this modest return of gongs equated to a shortage of fame. A contemporary playwright, the comedian Aristophanes, made sure everyone in Athens, even those uninterested in tragedy, knew all about Euripides.

Aristophanes, along with other exponents of Old Comedy, used rumors about Euripides as material to create a comic alter-ego who was not merely joked about, but lampooned directly whilst appearing as a character in several plays.

Common jokes were:

That Euripides’ wife was having an affair with his lodger, who also happened to collaborate with Euripides in writing some of his plays.

That this cuckolding created in him such bitterness that many of his plays ended up propounding a theme of misogyny.

That he was an atheist and blasphemous towards the Greek gods.

That he was responsible for making tragedy less lofty e.g. whilst Aeschylus uses kings, gods and heroes as characters, Euripides uses beggars, cripples and the working-classes. And even when portraying kings, they are clad in rags and slovenly.

That his mother sold cabbages in the agora – an early example of a “yo momma” joke i.e. “yo momma so poor, she sells cabbages in the agora”.

That he, like his contemporary Socrates, subverted the moral order of the day.

It is worth remembering that Aristophanes, like all comedians, was more concerned with laughs than with truth. Indeed, it is almost impossible to imagine that Euripides was from anything other than a high-class family and enjoyed a fine education.

Whether or not his wife was playing away, we do not know for sure, but anybody who closely studies his plays would find it hard to conclude he was a misogynist. In fact, even more than his great rivals, Euripides treats his female characters with great sensitivity and sympathy, as well as portraying them as independent and intelligent.

Moreover, it is quite likely that Euripides would have actually been in the audience when some of these zingers landed, making the impact of the joke two-fold. First, as the audience appreciated what the actor said, then second, as the audience turned as one to the embarrassed, angry, or perhaps, laughing Euripides.

One area where Aristophanes did not poke fun at Euripides was that of peace and war. The 5th century BC was a time of relentless fighting for Athens and both men used their art as a medium to criticize either politicians or the very nature of war itself. Indeed, it’s possible one reason Euripides was not a man appreciated in his own time was because of his unwillingness to slap a ‘support our troops’ sticker on the front of his programs.

Whilst accusations he was a pacifist were perhaps a little wide of the mark, both he and Aristophanes stood out as men who used their talents to campaign against the involvement of Athens in expensive, devastating, and pointless military campaigns.

Much as Euripides’ attempts to win favor with the public were to no avail, his efforts to influence popular opinion on foreign policy matters were equally fruitless. Two years after his death, Athens fell to the Spartans.

The cradle of democracy never recovered its status as the leading light of Western civilization.

Euripides’ legacy is a theatrical, not a political one. He changed theater from a vehicle for education and moralizing to one of doubt and introspection. Whilst it is his complexities, his ambiguities and his lack of conformity that brought him up against such resistance in his own time, it is perhaps those same qualities that keep him relevant and endear him to so many today.

“yo momma so poor, she sells cabbages in the agora“

😂😂😂

“It is the wise man who stays home when he is drunk.” —Euripides