Dear Classical Wisdom Reader,

What does it mean to be wise?

It’s a big question.

For the ancient Greeks, wisdom was personified in the goddess Athena. She casts a long shadow over Greek culture and history… and literature.

Wherever and whenever she appeared in Homer or in Greek tragedy, it meant something of great importance was happening. Today’s article looks at some of these appearances, including her role in helping to establish democracy…

Now, if you’re interested in learning more about ancient literature or wisdom, our much-loved video course The Essential Greeks is starting again on July 1st!

Through a combination of videos, webinars, quizzes and more, you can go deeper into the world of ancient history, literature, philosophy and mythology.

We’ll be looking at some of the most celebrated philosophers and writers of all time, including Homer, Plato, Aristotle, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and more.

You can enroll for that HERE!

Even better, for a limited time, you can enroll for the special reduced price of $149.

Whether you’re a newcomer or a longtime devotee of the Classics, there will be wisdom for you to discover on The Essential Greeks.

And I think we can agree that one thing’s for sure: we could all do with a bit more wisdom these days…

All the best,

Sean Kelly

Managing Editor

Classical Wisdom

Literature of Wisdom: Athena

by Sean Kelly

She’s one of the most famous and prominent of the Greek deities. Her symbol – the owl – still stands proudly, millennia later, as an emblem of wisdom.

Yet what do the ancient texts actually say about her? Who is she, and what does she do?

What do we know about the Goddess of Wisdom?

Athena in Homer

The Iliad and the Odyssey were both of central importance to ancient Greek society. Even today, they are many people’s first exposure to the world of the Classics. Athena’s role in both, while comparatively small in terms of ‘screentime’, is key to the action of the story.

Of the two Homeric poems, Athena plays a much larger role in the Odyssey: she essentially acts as the protector of the protagonist, Odysseus. At various points across Odysseus’ journey, it is Athena’s help and guidance which allows the cunning hero to escape to safety. Moreover, it is Athena’s request to Zeus that allows Odysseus to leave the island of Circe, where he is stranded when we first encounter him in the Odyssey.

Some have taken this to diminish the role of Odysseus himself. Yet the interaction between the human and the divine in Greek literature is more complex than that. Odysseus’ own qualities of cunning and guile are what win him the approval of the goddess. It is this resourcefulness which makes him worthy of having a god consistently intervene on his behalf.

Odysseus’ personality is defined by cleverness and using his wits. That these are traits similar to those possessed by the goddess herself is significant.

A direct parallel is drawn between Odysseus and Athena in two incidents that bookend the epic. Early on in the Odyssey, Athena appears to Odysseus’ son Telemachus in disguise. Towards the end of the epic, it is Athena that allows Odysseus to take on the form of a beggar, which allows him to re-enter Ithaca disguised. Odysseus has learned the importance of having a concealed identity, something which Athena knew from the beginning…

Athena’s presence in the Iliad is notably less prominent. Nevertheless, she also acts as something of a guide to Achilles at key moments throughout. For instance, she is present at the infamous quarrel of Agamemnon and Achilles over Briseis which opens the epic. She helps stay the anger of Achilles, preventing him from killing Agamemnon outright!

Athena in Greek Tragedy

Athena was, naturally enough, the patron of her namesake city, Athens. The Festival Dionysia, where Greek tragedies were staged, actually took place in Athens. So, the audience for Greek tragedies consisted primarily of Athenians. The characterization of Athena in Greek tragedies is, unsurprisingly, consistently positive.

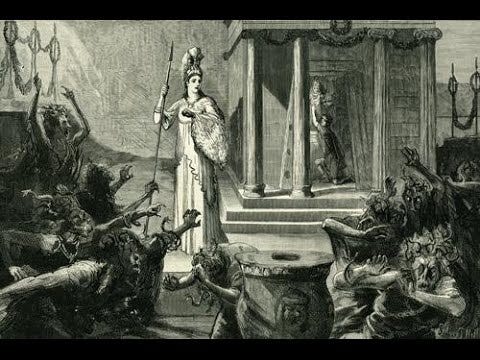

Perhaps Athena’s most important role in Greek tragedy is in the Eumenides by Aeschylus. Athena appears in the third and final play of the Oresteia trilogy, where she effectively acts as a judge in the world’s first courtroom drama.

A quick recap for those unfamiliar with the earlier plays in the trilogy: Orestes is on trial for having killed his mother Clytemnestra in the trilogy’s previous play, Libation Bearers. He was enacting vengeance for the death of his father Agamemnon, which was orchestrated by Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus in the opening play in the trilogy, simply titled Agamemnon.

Orestes and his family are trapped by an older moral system based on vengeance, which seems to only lead to further and further bloodshed. Their blood-for-blood family drama stretches back to earlier generations, and seems to have no end in sight…

Yet the trial, and Athena’s role within it, point to a new way.

The deciding vote as to whether or not Orestes should be considered guilty of his crimes is granted to Athena. The ruling frees Orestes from punishment by the Furies (ancient spirits of vengeance), while also granting the Furies a place of honor in a new system of justice.

This ruling is seen as representing, in dramatic form, the establishment of democracy.

Athena also appears in a number of Euripides‘ plays, such as Iphigeneia Among the Taurians, The Suppliants and Ion. In each of these plays, she acts in the role of deus ex machina, a term that literally means ‘god from the machine’.

Although that term might conjure up the sort of imagery you’d see in a Marvel or Matrix movie, it’s real meaning is much more straightforward than it might sound.

The ‘machine’ is in fact the mechane, a sort of crane that formed part of the ancient Greek stage. It was a heightened platform, placed physically above the action of the rest of the scene, to signify to the audience that the actor was playing a god.

Whenever the drama has reached a point near the climax of the story, and all the play’s problems seem unsolvable, a god appeared on this stage. They then go on to very effectively resolve the conflict of the play, by telling each of the characters what they must do. It’s not always been a popular technique in tragedy – Aristotle was critical of the convention of the deus ex machina in his treatise on tragedy, the Poetics. Today, many would still agree with him. Yet it is a fitting role for Athena to fulfill: it’s consistent with how Athena is characterized throughout ancient literature.

There is, of course, an even more vast body of myths that surround Athena. Many of these belonged to the lost poems of the Epic Cycle. We still know many of these stories – for instance, that she was one of the three goddesses Paris had to choose between in the “Apple of Discord” story which precedes the Trojan War. Yet so much is also lost.

There’s an obvious sadness in acknowledging this. Yet perhaps the real wisdom comes in being grateful for the astonishing power and legacy of the literature we have received from the ancients.

Surely Athena would approve of that!

No olvidemos que Atenea es también la diosa de la guerra...

Sean, it can be cause for sadness to dream of all the stories lost to humanity’s messiness. Yet, the many examples of wisdom and art we do have are mostly unheeded and unappreciated. That makes things sadder still.