Artemis: Launching the Wonder Woman of the Ancient World

Understanding the Name Behind Tomorrow's Historic Mission

Dear Classical Wisdom Reader,

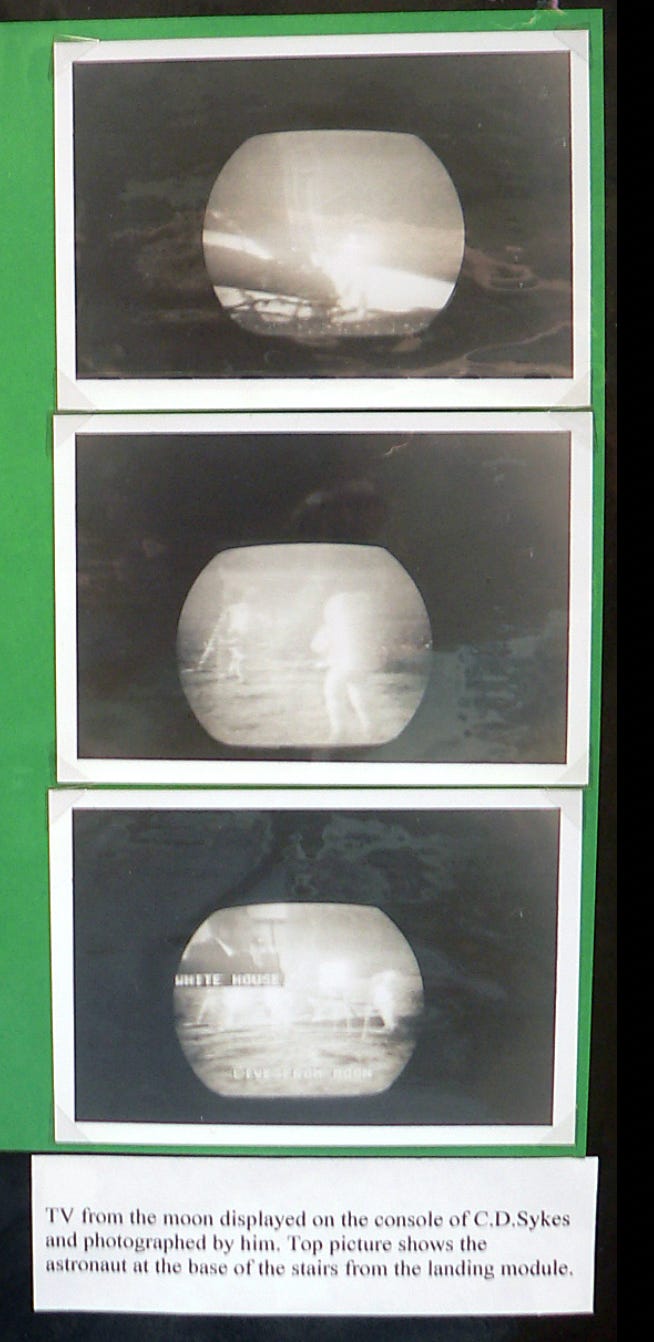

News is that tomorrow’s historic launch is a ‘go’. NASA will indeed try to launch its Artemis 1 moon mission this weekend.

For someone who is both an ancient Greek mythology fan, and has long followed the history of NASA, this is very exciting.

In fact, my late stepfather worked in Mission Control for most of the Apollo project (including the heart-wrenching 13th… he said he could never watch the movie, the real thing was difficult enough).

But why was the US Human Spaceflight called Apollo (of all things) in the first place?

According to NASA manager Abe Silverstein, the program was named after Apollo, the Greek god of light, music, and the Sun, saying, "I was naming the spacecraft like I'd name my baby….Apollo riding his chariot across the Sun was appropriate to the grand scale of the proposed program.”

And so, it does seem appropriate that almost exactly 50 years to the date after the last Apollo mission (Apollo 17, December 19, 1972), that NASA will launch a rocket bearing the Greek god’s sister’s name.

But who was Artemis? And is it possible she’s an even better namesake for this ambitious project? Or is it not appropriate at all?

Read below to learn more about the Wonder Woman of the Ancient world… and comment below what you think about the name.

All the best,

Anya Leonard

Founder and Director

Classical Wisdom

In Case You Missed It: Articles From This Week

Artemis: Wonder Woman of the Ancient World

Written by Katherine Smyth Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

There’s more to this goddess than her Amazon-like reputation. Artemis, daughter of Zeus, twin-sister of Apollo, and with a host of temples dedicated to her, was once part of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. More than just the goddess of the hunt, her influence can be seen in pop-culture as a reinvented feminist icon.

A Helpful Birth

When Leto, Artemis’ mother, was pregnant with her divine twins, her arch-nemesis was furious. Hera was so enraged, over Zeus’ philandering, that she forbade Leto to give birth on either mainland Greece or any island. This caused something of a predicament for the heavily pregnant Titan.

However, the island of Delos disobeyed Hera and offered the mother-to-be sanctuary on the island. It is here that Artemis made her arrival, or at least one version of events has it so. According to the Homeric Hymn, Artemis was born on Ortygia. But, as Leto was also worshipped at Phaistos, Cretan mythology says the twins were born on the island of Paximadia (as it is known today).

Another mystery is which twin was born first. The Homeric Hymn cites the locations thus:

“Rejoice, blessed Leto, for you bare glorious children, the lord Apollon and Artemis who delights in arrows; her in Ortygia, and him in rocky Delos.”

However, one of Artemis’ most endearing characteristics comes from the story in which she was born first. As the elder twin, she then helped bring forth her brother, the great Sun-god Apollo.

Her childhood is shrouded in mystery, with the only surviving tale mentioned in the Iliad. Here, the goddess is spoken of as a girl who was punished by Hera, and who then seeks solace in Zeus’ lap, a distressed daughter seeking comfort from her father. What is known is that Artemis follows in the footsteps of Athena and Hestia; she decides to remain a maiden.

This lifelong commitment appears to be supported by her companions, who also remained virgins, with Artemis closely guarding her own virginity. It’s also believed that she was chosen by the Fates to be a goddess of midwifery since she was involved in successfully delivering her brother.

Callimachus, the Libyan-Greek poet, describes how Artemis spent much of her formative years: seeking out what she would need as a huntress. He also describes how she gained her iconic bow and arrows: from another island near Ortygia, the small island of Lipara, where Hephaestus and the Titan Cyclopes worked in the Olympian forge.

He describes Artemis’ bravery, that where Oceanus’ daughters were afraid, the young goddess was bold and asked for a bow and arrows, first practicing on tress and then on wild beasts. Next, she sought out Pan in the wilderness, where the god of the forest then gave her seven female and six male dogs for her hunting pack. Artemis then tracked and trapped six golden-horned deer for her chariot.

Artemis and love

As a sworn virgin, Artemis had no consort and cared only for hunting, and her hunting companion, Orion. Sadly, Orion was killed and the details of his death are unclear; some attribute blame to Artemis herself, others to Apollo or Gaia who did not approve of the relationship.

Artemis’ affections are also sought by Alpheus, a river god, Bouphagos, a Titan son of Iapetus, and Siproites a mortal boy. Alpheus, besotted with Artemis, becomes frustrated by her refusal of interest and decides to trap her. Artemis suspects Alpheus is scheming, and when he attempts to rape Arethusa, thinking it is Artemis, she saves her attendant by transforming Arethusa into a spring in the temple Artemis Alphaea, near Letrini

Both Bouphagos and Siproites meet with a similar fate; at Mount Pholoe, Artemis strikes Bouphagos after she reads his thoughts and learns of his plans to rape her. Siproites has a life-transforming experience, being transformed into a girl, after he either sees Artemis naked or attempts to rape her.

Crime and punishment

But perhaps the best-known stories of Artemis are those involving Actaeon and Adonis. Actaeon was another of Artemis’ hunting companions, and like his immortal friend, he had a pack of hunting dogs. Whether it was an act of hubris, like seeing the goddess naked in her sacred spring, or as a result of him attempting to force himself on her in that condition, for these acts he was transformed into a mighty stag, which was then hunted down and devoured by his own hounds.

Adonis, for his part, was foolish enough to boast that he was a greater hunter than Artemis, and for this, she sent a wild boar to kill him as punishment. In later versions of this myth, it is believed that this was a revenge killing, due to Aphrodite being responsible for killing Hippolytus, one of Artemis’ favorites.

These two are not the only ones to feel the sting of this archer’s aim. The Aloadae or twin sons, Otos and Ephialtes, were two enormous and fast-growing offspring of the god Poseidon. They were unable to be killed unless they killed each other, and as they grew more and more aggressive and unstoppable in their pursuits, they set their eyes on taking Artemis and Hera as wives.

However, where the other gods were afraid of the Aloadae, they were stopped by Artemis’ bravery; by capturing a deer, or transforming herself into one, it dived between the two monstrous men and they speared each other to death in an attempt to kill it.

Artemis’ other stories

There are many more stories about Artemis and various mythological characters. There’s the tale of Callisto, a woman who was raped by Zeus or Apollo, and who bore a son as a result. Outraged, either Hera or Artemis changed Callisto into a bear, only for her son, Arcas, to almost kill her. Their story ends well though, with either Artemis or Zeus placing mother and son in the heavens, as the constellations Ursa Minor and Ursa Major.

Agamemnon was punished by Artemis too, for killing a stag in a sacred grove, and then boasted that he was a better hunter than her. As a result, when it came time to sail for Troy and the Trojan War, Artemis calmed the seas and delayed the king’s departure. How did he appease the insulted goddess? By offering the human sacrifice of his daughter, Iphigenia. Fortunately for the girl, Artemis swooped in at the last second and carried her away, where the princess would become an immortal companion to the goddess.

Another common theme in stories relates to Artemis and jealousy, two such stories involve Niobe, a Queen of Thebes, and the Pokis princess Chione, both of which felt the sting of Artemis’ retribution after boasts of their superior beauty.

Artemis is also known for having saved the infant Atalanta by sending a female bear to nurture the infant. Unfortunately, although Atalanta never made the claim herself, when others exclaimed that her hunting prowess must be greater than that of the goddess, Artemis then sent a bear to hurt her.

Worship of the goddess

As the goddess of hills and forests, Artemis was worshiped throughout much of ancient Greece. It is on Delos, the ‘center’ of the Cycladic islands, that the worship of Artemis is best known. However, she also had dedicated followers at Brauron and Mounikhia, both near modern-day Piraeus, and in Sparta. The Spartans revered her so much they often made sacrifices to her before embarking on a new military campaign.

You can often spot Artemis easily in paintings and sculptures, due to her often being depicted with a bow and arrows, accompanied by a deer, or set in a forest location. Some of her other symbols include chariots, spears, nets, the lyre, hunting dogs, bears, boars, guinea fowl, and the buzzard hawk.

The Athenians also encouraged serving the goddess by sending their daughters to the sanctuary. Whilst there, the girls were to ‘act the bear’ as penance for the village inhabitants killing a wild bear. The villagers had fed a bear until it became tame, the bear killed a girl by accident or in self-defense, and the girl’s brothers then slaughtered the bear, which enraged Artemis in the process. The arktoi, of little she-bears, as they were known, would serve the goddess for one year, before they became women and of marriageable age.

There are numerous Athenian festivals held to honor Artemis, including celebrations at Mounikhia, Brauronia, Elapheboila, and Kharisteria, and the Spartan festival of Artemis Orthia. Artemis was also worshipped as a goddess of childbirth and midwifery, due to her involvement in delivering her twin brother, Apollo. She was also feared for this reason, as deaths during pregnancy were not uncommon, and the passing of both mother and child was seen as linked to her.

But, most of all, Artemis is known for retaining her maidenhood, for refusing to marry or take a lover. She is one of the few virgin goddesses, however, that is both worshipped for celibacy and also motherhood and childbirth. As such, she is also associated with Persephone and Demeter, as according to Herodotus, they were worshipped as mother goddesses.

Finally, Artemis left her mark on the ancient world in the form of her temple at Ephesus, in Ionia, which became one of the Seven Wonders of the (ancient) World. This temple is perhaps the best-known center of her worship outside of Delos.

Legacy

Artemis is still honored today. Her name is born by several important astrological achievements: 105 Artemis, Artemis crater, Artemis Chasma, Artemis Corona, and the Artemis lunar program.

Artemis also lends her name to a tiny aquatic species: sea monkeys or Artemia salina, which live in salt lakes and seldom in open waters – except for along the Aegean coast near where her temple stood at Ephesus.

Perhaps one of the most surprising legacies though is her association with her Roman counterpart. Whilst the Greeks know her as Artemis, the Romans preferred the name Diana. Diana, of course, is the daughter of Jupiter, the Roman form of Zeus, King of the Gods. As such, Diana is a princess.

That name may sound familiar, and with good reason. Diana Prince is the alias used by Wonder Woman when living in the mundane world. Wonder Woman, of course, is an Amazon who was born to the Queen of the Amazons and is a daughter of none other than… Zeus. So, whilst Gal Gadot is the latest to reprise the role, it is plausible that the inspiration for the original character does, in fact, stem from the ancient Greek goddess, Artemis.

Conclusion

The story, or stories, of Artemis, are fascinating and have certainly spanned the ages. From being born on the shores of a distant island to helping deliver her protective brother, Apollo, through to her various adventures with other Classical heroes, Artemis’ journey is an incredible one.

What stands out most though, is Artemis’ steadfastness and unwavering belief in herself, and her purpose in life. Whilst it’s true that she’s not always benevolent, and can have a vicious temper, she is also the goddess of childbirth and midwifery, both of which demand a strong degree of empathy and understanding.

Artemis is known throughout the ancient and modern world, as a woman of intelligence, determination, righteousness, and as a protector of defenseless women. She is respected as a woman who knows her own mind, and who will not be swayed into conforming to social norms to appease others.

Now, in the 21st century, we can see the effects of her as a role model; the Suffragette and Feminist movements of the early 20th century as well as for women standing up for themselves and speaking their truths today. Artemis may not be a name readily on women’s lips anymore, but her influence is far from declining…

… as evident by tomorrow’s launch!

Hi, I like the information about Artemis’ mythology, but I don’t think she’s a “feminist icon” at all and tells me more about the writer’s own views and interpretations than it does about her “influence”. This is evidenced by the fact the writer thinks there was a “feminist” movement in the early 20th century (there wasn’t until the 70s, and there were/are many problems with the movement/ideology, but that’s a story for another day) and the fact she doesn’t seem to know the difference between the suffragist and suffragette movement: the former was a movement including both men and women to get both women AND working-class men the vote in the UK, the latter was a counterproductive “movement” that didn’t achieve anything, much like BLM and Antifa today. The fact that history books focuses mostly on the suffragettes thing is one the great errors and misconceptions of history, no doubt helped by “feminists” who aren’t above trying to change history to suit their ends.

Anyway, I’m going on a tangent but the point is one of the reasons I read this newsletter is to get away from this kind of cliched, subjective writing and expected better from it. This is exactly the kind of PC stuff it’s supposed to be against but obviously not. And as a final note, these new lunar missions are not “historic” as it’s just copying what they already did 50 years ago and still think the name is silly. Perhaps they should have a program where they send men to Mars and women to Venus instead, at least that would be fitting.

I still like CW, but would prefer more mythology-based writing that doesn’t attempt to fit it in a modern context where there isn’t one, thanks.