Alcestis: The Least Tragic Tragedy

by Sean Kelly, Managing Editor, Classical Wisdom

What do you think of when hear the words “Greek tragedy”?

I’ll bet that the images that spring to mind tend to be dark and dramatic. Yet not all tragedies fit this preconception. Not all tragedies are quite so…. Tragic.

For instance, there were the Satyr plays. In ancient Greece, tragedies were staged in trilogies, accompanied by an additional play in a separate genre, the Satyr play. These were much more comedic and farcical in nature than the sometimes austere world of tragedy. In honour of the god Dionysus, centaurs drank and caroused, causing mischief and chaos in irreverent settings. Only one of these plays has been handed down to us, the Cyclops, once more by Euripides, which is a playful retelling of Odysseus’ encounter with the one-eyed Polyphemus. It is from these plays such as these that we get the word satire.

There is, however, another play that is neither comedy, tragedy, nor satyr play. It is a unique blend of all these forms, and yet utterly unlike anything else handed down from the ancients. The story has more in common with a fairy-tale than many of its peers in the corpus of Greek tragedy. It is Alcestis.

Of the three Greek tragedians, Euripides is by far the most unconventional, frequently challenging the norms and conventions of the form. It is from these experiments that a play as unusual but ultimately moving as Alcestis emerges.

Unlike the more familiar stories of the Theban Oedipus cycle or the unhappy tales of the House of Atreus, Alcestis deals with a lesser known, more unusual branch of Greek mythology. Alcestis tells the story of the title character and her husband, Admetus. Due to a complicated mythical backstory, the god Apollo was forced to work as a labourer. During this humbling experience, Admetus, the human king of Thessaly, treated the diminished god with great kindness.

The god, eager to repay a human kindness, has arranged a special favour for Admetus. He is granted the chance to live a longer life than he had been allotted by the Fates, and in doing so, frustrate death. Yet, this gift comes with a cost.

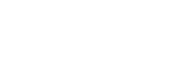

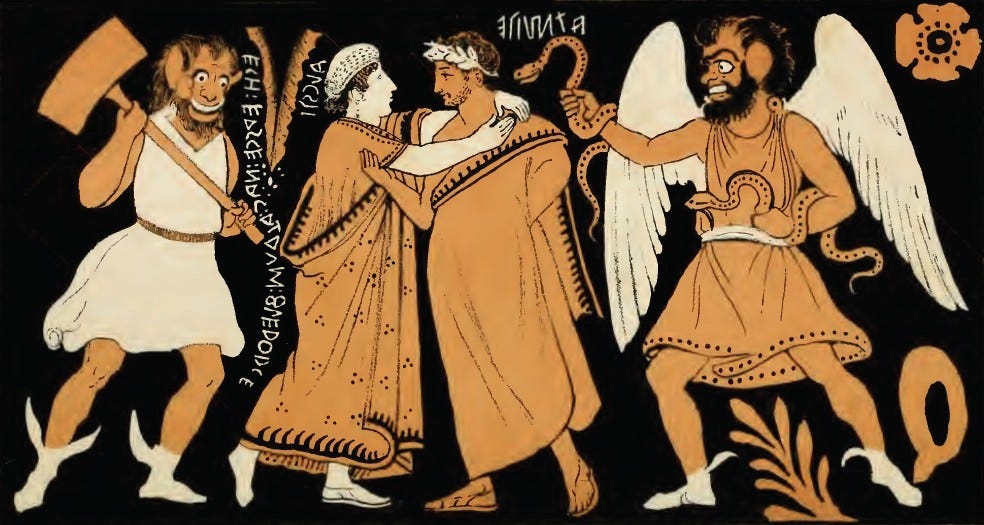

The play begins with a conversation between Apollo and Death (or Thanatos in Greek). Thanatos is eager to the reclaim what Apollo has denied him: someone now has to die in Admetus’ place. Admetus’ father refuses to do so, and so Admetus’ wife, Alcestis, chooses to die in her husband’s place. Much of the early part of the play is dedicated to the household’s anticipation of Alcestis’ death. As is typical of Euripides, situations are inversed: someone still alive is being mourned.

Alcestis dies, and Admetus is wracked by grief and despair. Yet, despite this, hope may yet remain with the arrival of Heracles, Alcestis being one of a number of tragedies featuring the demigod. Here, he is characterised very differently to how he appears elsewhere in tragedy. In Alcestis, Heacles is as a dim-witted, yet kindly party boy.

Heracles is blissfully unaware that his friend Admetus is in mourning; he arrives eager to drink, party and have fun. Admetus decides to not burden his guest with the sad news. The world of the Satyr play and Tragedy now collide in a way that enhances each other. The starkness of Admetus’ grieving for his wife is set against the oblivious, fun-loving Heracles, to great effect.

Whenever Heracles does discover the truth, the demi-god realizes that he is, in fact, uniquely qualified to deal with the situation, being one of a very small group of Greek heroes who can travel to the Underworld. Eager to help his grieving friend, Heracles exits the scene to go and retrieve his friend’s wife from Hades.

What follows is one of the most moving scenes in Greek theatre. Herakles returns to the party with a veiled woman in tow. He offers her to Admetus as a new wife, but the grieving King finds this highly inappropriate. Eventually he is goaded, against his judgement in to seeing just who it is beneath the veil…

Considering that the play begins with a conversation between Apollo and Death, it ends on a very human emotion: the joy of reunion. For all the grandeur of the mythic backdrop and quarrelling divinities, the Alcestis is, at core, about the love between a married couple.

It is the earliest play we have by Euripides, having been staged in 438 BCE. Considering how much ancient literature is lost, it is a gift that this strange, tragi-comic fairy-tale can still resonate.

And thanks to Euripides for that delicately insightful tale of the love of a man for a woman in this mortal vail.

That was beautiful