12 Ancient Greek Terms that Should Totally Make a Comeback

Eudaimonia, Arete, and much more...

Dear Classical Wisdom Reader,

Learning Ancient Greek can be… challenging.

For one thing, there are competing dialects (as was discussed in our Podcasts with the Professor of Linguistics at the University of Cyprus.) As such, there are times when we aren’t even sure how the word is pronounced.

There are also like 5 different translations for every word, which gives translators a huge artistic license, truth be told. Just look at the huge variety of translations of the first line of The Odyssey! There are over 70… and man oh man do they change the tone of the epic, to say the least.

Indeed, it can be difficult to decide which version of the word the author intended because we just don’t think exactly like ancient Greeks. The huge differences in time and culture can make it tricky to figure out what they really meant.

So while actually dedicating years to learning this beautiful and complicated ancient language might not be the most practical use of your time, I do think you should at least learn a few of the most important concepts.

In fact, I reckon these 12 terms should definitely make a comeback in our current society… and that we might be a lot better for it… check them out below and let me know if you agree.

Enjoy!

All the best,

Anya Leonard

Founder and Director

Classical Wisdom and Classical Wisdom Kids

12 Ancient Greek Terms that Should Totally Make a Comeback

1. Eudaimonia (Greek: εὐδαιμονία)

Eudaimonia is regularly translated as happiness or welfare; however, “human flourishing or prosperity” and “blessedness” have been proposed as more accurate translations. In Aristotle’s works, eudaimonia was used as the term for the highest human good, and so it is the aim of practical philosophy, including ethics and political philosophy, to consider (and also experience) what it really is, and how it can be achieved.

2. Arete (Greek: ἀρετή)

Arete in its basic sense, means “excellence of any kind”. The term may also mean “moral virtue”. In its earliest appearance in Greek, this notion of excellence was ultimately bound up with the notion of the fulfillment of purpose or function: the act of living up to one’s full potential.

In the Homeric poems, Arete is frequently associated with bravery, but more often with effectiveness. The person of Arete is of the highest effectiveness; they use all their faculties—strength, bravery, and wit—to achieve real results. In the Homeric world, then, Arete involves all of the abilities and potentialities available to humans.

In some contexts, Arete is explicitly linked with human knowledge, where the expressions “virtue is knowledge” and “Arete is knowledge” are used interchangeably. The highest human potential is knowledge and all other human abilities are derived from this central capacity.

3. Phronesis (Greek: φρόνησῐς)

Phronesis is a type of wisdom or intelligence. It is more specifically a type of wisdom relevant to practical action, implying both good judgement and excellence of character and habits, or practical virtue. As such, it is often translated as “practical wisdom”, and sometimes as “prudence.” Thomas McEvilley has proposed that the best translation is “mindfulness”

4. Kleos (Greek: κλέος)

Kleos is often translated to “renown”, or “glory”. It is related to the word “to hear” and carries the implied meaning of “what others hear about you”. A Greek hero earns kleos through accomplishing great deeds.

Kleos is invariably transferred from father to son; the son is responsible for carrying on and building upon the “glory” of the father. This is a reason for Penelope putting off her suitors for so long, and one justification for Medea’s murder of her own children was to cut short Jason’s kleos. Kleos is sometimes related to aidos — the sense of shame.

5. Xenia (Greek: ξενία)

Xenia means “guest-friendship” and is the concept of hospitality. It includes the generosity and courtesy shown to those who are far from home and/or associates of the person bestowing guest-friendship. The rituals of hospitality created and expressed a reciprocal relationship between guest and host expressed in both material benefits (such as the giving of gifts to each party) as well as non-material ones (such as protection, shelter, favors, or certain normative rights).

6. Aidos (Greek: Αἰδώς)

Aidos was actually the Greek goddess of shame, modesty, respect, and humility. Aidos, as a quality, was that feeling of reverence or shame which restrains men and women from wrong. It also encompassed the emotion that a rich person might feel in the presence of the impoverished, that their disparity of wealth, whether a matter of luck or merit, was ultimately undeserved. Ancient and Christian humility have some common points, they are both the rejection of egotism and self-centeredness, arrogance and excessive pride, and is an recognition of human limitations. Aristotle defined it as a middle ground between vanity and cowardice.

7. Nostos (Greek: νόστος)

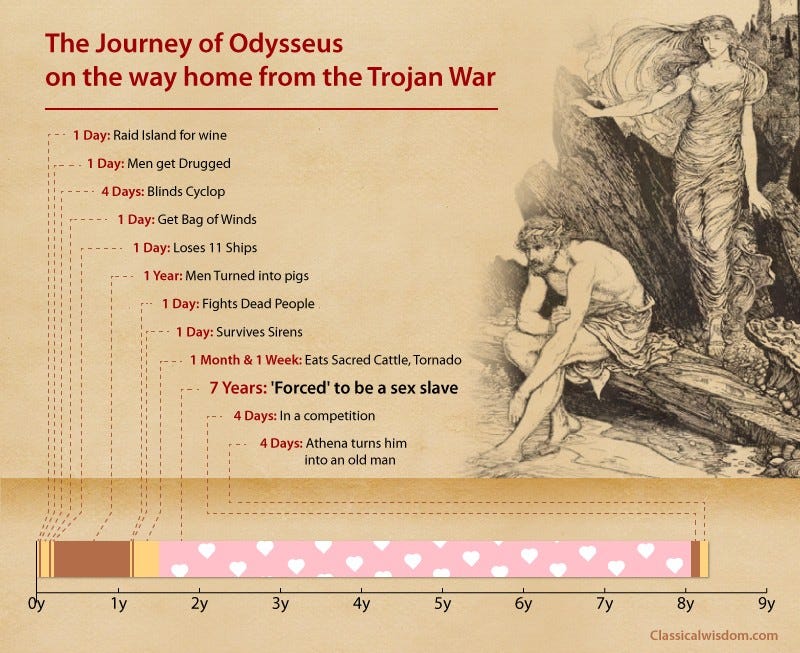

Nostos is a theme used in Ancient Greek literature which includes an epic hero returning home by sea. In Ancient Greek society, it was deemed a high level of heroism or greatness for those who managed to return. This journey is usually very extensive and includes being shipwrecked in an unknown location and going through certain trials that test the hero.The return isn’t just about returning home physically but also about retaining certain statuses and retaining your identity upon arrival. The theme of Nostos is brought to life in Homer’s The Odyssey, where the main hero Odysseus tries to return home after battling in the Trojan War.

Incidentally, the word nostalgia was first coined as a medical term in 1688 by Johannes Hofer (1669-1752), a Swiss medical student. It uses the word νόστος along with another Greek root, άλγος or algos, meaning pain, to describe the psychological condition of longing for the past.

8. Oikos (Greek: οἶκος)

Oikos refers to three related but distinct concepts: the family, the family’s property, and the house. Its meaning shifts even within texts, which can lead to confusion.

The oikos was the basic unit of society in most Greek city-states. In normal Attic usage the oikos, in the context of families, referred to a line of descent from father to son from generation to generation. Alternatively, as Aristotle used it in his Politics, the term was sometimes used to refer to everybody living in a given house. Thus, the head of the oikos, along with his immediate family and his slaves, would all be encompassed. Large oikoi also had farms that were usually tended by the slaves, which were also the basic agricultural unit of the ancient economy.

9. Apatheia (Greek: ἀπάθεια)

In Stoicism, Apatheia refers to a state of mind in which one is not disturbed by the passions. It is best translated by the word equanimity rather than indifference. The meaning of the word apatheia is quite different from that of the modern English apathy, which has a distinctly negative connotation. According to the Stoics, apatheia was the quality that characterized the sage.

10. Ataraxia (Greek: ἀταραξία)

Ataraxia literally translates as “unperturbedness”, but is generally considered as “imperturbability”, “equanimity”, or “tranquillity”. It was first used by Pyrrho and subsequently Epicurus and the Stoics for a lucid state of robust equanimity characterized by ongoing freedom from distress and worry. In non-philosophical usage, the term was used to describe the ideal mental state for soldiers entering battle.

Achieving ataraxia is a common goal for Pyrrhonism, Epicureanism, and Stoicism, but the role and value of ataraxia within each philosophy varies depending their philosophical theories. The mental disturbances that prevent one from achieving ataraxia vary among the philosophies, and each philosophy has a different understanding as to how to achieve ataraxia.

11. Doxa (Greek: δόξα)

Doxa means common belief or popular opinion and comes from verb δοκεῖν dokein, “to appear”, “to seem”, “to think” and “to accept”. Used by the Greek rhetoricians as a tool for the formation of argument by using common opinions, the doxa was often manipulated by sophists to persuade the people, leading to Plato’s condemnation of Athenian democracy. It is used in direct contrast to Episteme and Techne.

12. Episteme (Greek: ἐπιστήμη) and Techne (Greek: τέχνη)

Episteme can refer to knowledge, science or understanding, and which comes from the verb ἐπίστασθαι, meaning “to know, to understand, or to be acquainted with”. The word “epistemology” is derived from episteme.

Meanwhile Techne is often translated as “craftsmanship”, “craft”, or “art”. While it resembles epistēmē in the implication of knowledge of principles, techne differs in that its intent is making or doing as opposed to disinterested understanding. However, Plato regularly used the two terms interchangeably, and to the ancients, techne and episteme simply mean knowing and “both words are names for knowledge in the widest sense.”

Maybe #13 could be Isonomia (equality before the law) could make it a baker’s dozen...

I WILL REFER YOU TO THE DELPHIC ORDERS!